“The greater fool is actually an economic term: it’s a patsy. For the rest of us to profit, we need a greater fool, someone who will buy long and sell short. Most people spend their lives trying not to be the greater fool: we toss him the hot potato, we dive for his seat when the music stops. The greater fool is someone with the perfect blend of self-delusion and ego to think that he can succeed where others have failed. This whole country was made by greater fools.”

– Aaron Sorkin’s character Sloan Sabbith from The Newsroom

Imagine if a friend, who’s an experienced entrepreneur, approached you about investing in a new business. You would probably discuss the business concept, how it would be structured, the development and marketing strategy. If they were looking for a private loan, you might discuss the contractual terms of repayment and interest. If they were looking for an equity partner, you might discuss common legal arrangements ranging from a Limited Liability Partnership to a Venture Capital Partnership. If the business is organized as a Limited Liability Corporation they might offer you a membership interest with contractual terms of dividends on profits.

If they are organized as a corporation, they may offer you shares of stock in the company.

A stock is a security representing ownership of a fraction of the corporation. Units of stock are called shares. Investopedia notes that these shares, “entitle the owner to a portion of the corporation’s profits equal to the number of shares owned.”

Unfortunately, as we’ll see, Investopedia’s claim is not true.

Since you’re an early investor, your friend might give you an option to invest in shares of preferred stock or common stock. Preferred stock offers a fixed dividend that is paid out before any dividends to shareholders of common stock but has the caveat that it does not come with voting rights. Preferred stock is a popular way to attract capital from early investors who just want profits. Common stock doesn’t guarantee dividends, but sometimes offers voting rights.

If the last option of common stock shares doesn’t seem like a particularly attractive deal compared to the many aforementioned options, that would be a reasonable observation. The only way that shares of common stock would provide you a return on your investment is if the company was profitable AND elected to pay a dividend, OR if the price of the stock appreciated on the open market. If your friend’s company is small, private and has limited potential for growth, your purchase of common shares would verge on a charitable donation – or a bet with very long odds. If your friend convinced you to purchase non-voting shares, what would you have?

Maybe a cool piece of paper?

Most of the stock invested in public markets is common. Webster’s 1828 dictionary defined common as, “Ordinary or not of superior excellence.” The word itself rings with feudal overtones – common stock for the commoners, the serfs, the hoi polloi, the prols, the plebians, the people in “flyover country.”

Before the 20th century, a share of common stock in a company that did not regularly distribute profits from the enterprise in the form of a dividend was considered practically worthless; fodder for the gambits of greater fools. The entire point of buying a share in a venture was to contribute capital in exchange for a share of the future earnings. Perhaps it was the agrarian cultural sensibility that could clearly distinguish productive and non-productive assets. Flat, fertile land is far more productive and therefore more valuable to a farmer than mountainous, rocky terrain. That concept makes so much practical sense that many (including Investopedia, apparently) continue to propagate the myth that a shareholder today owns a piece of a business that works for them and pays them. While that’s hypothetically possible, the business has absolutely zero obligation to pay you anything. The par value is effectively nothing, and any voting rights (that few exercise), may be changed or diluted by the company at any time.

Divi-when?

Since 1900, the role of dividends in stock market returns has steadily diminished, especially when measured as a percentage of total returns. In the mid-20th century—particularly during the 1940s through the 1970s—dividends were still the primary reason investors valued stocks at all. Dividends accounted for a substantial portion of investor gains, often contributing around 30–40% of total returns. This was a time when economic growth was slower, inflation was high, and dividends provided a reliable source of income.

Beginning in the 1980s and accelerating through the 1990s and 2000s, the emphasis shifted toward capital gains, driven by Margeret Thatcher’s farts, Ronald Reagan’s Brylcreem, the rise of growth stocks, especially in the tech sector, and the increasing popularity of stock buybacks. By the 1990s and into the 2010s, dividends contributed only about 15–20% of total returns, marking a roughly 60% decline in their relative importance compared to earlier decades. This trend has continued into the 2020s, where dividends remain a niche component of equity investing, overshadowed by price appreciation.

And we really appreciate that price, don’t we?

Today’s market participants are experiencing what anthropology nerds like the author call a form of cultural amnesia, or obsolete ritual, where the traditions of inherent value are assumed, but the original criteria has been lost or no longer applies.

Hmm. Why did this change? What were the reasons that drove this shift in investor preference?

With a bit of research we find various narratives. One is that companies that pass on profits to shareholders are not putting that money to work to grow market share, develop new products or innovate. Another is that dividends are a hallmark of late stage mature businesses that have expanded into most of their viable addressable markets, have exhausted most of their ideas and have limited growth potential. Tax policy also played a role, as investors in companies that offer high dividends are subject to taxation on those dividends, whereas “capital appreciation” costs nothing until you try to sell. The shift reflects broader changes in corporate behavior, investor preferences, and market dynamics over the past century.

So how do you make money on growth stocks that have never paid a dividend and never will? You have to sell it to a greater fool for more than you paid for it.

Share Buybacks

Back in the old days, when we made music with our hands, feet and mouths, we had to convince these big companies that manufactured and marketed records to give us recording contracts. Some record companies allegedly engaged in the practice of buying their own albums to artificially inflate sales figures, boost chart positions, and potentially secure more radio airplay. This was done to create a false impression of popularity and to potentially influence fans into purchasing the album.

Stocks are pretty much the same these days. Share buybacks are not only good, they are big league beautiful, and everybody says they’re really really great, so we should have more of them.

A popular narrative is that companies with excess profits – after they’ve reinvested as much as possible back into the business, acquisitions and management compensation – shouldn’t return money directly to investors, but instead buy their own stocks back on the open market. This is considered a win-win for investors, as it often inflates the bid price and reduces the number of shares outstanding, increasing their scarcity.

Before 1982, buybacks were largely considered illegal because they were viewed as a form of stock market manipulation. Umm, because they are. Under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, large-scale share repurchases could artificially inflate stock prices, mislead investors, and benefit insiders at the expense of the broader market. The concern was that companies could use buybacks to boost earnings per share and stock prices, thereby enriching executives whose compensation was tied to stock performance.

Stock buybacks became effectively legal in the United States in 1982, when the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted Rule 10b-18. This rule provided a “safe harbor” for companies repurchasing their own shares, shielding them from accusations of market manipulation as long as they followed specific guidelines—such as limiting purchases to no more than 25% of the stock’s average daily trading volume and avoiding trades at the beginning or end of the trading day.

So basically, new rules for just a little bit of market manipulation — but just a little. Totally fine.

The legalization of buybacks in 1982 marked a major shift in corporate finance, ushering in an era where buybacks became a dominant tool for returning capital to shareholders—often preferred over dividends due to their flexibility and tax advantages. Paul Allen was a big fan of stock buybacks. He wore Glasses by Oliver Peoples, double breasted suits by Jean Paul Gaultier, ties by Givenchy, complimented with oxfords by Salvatore Ferragamo.

Dilution

Stocks are kind of like olive oil. Everybody loves olive oil. Fancy grocers have entire aisles filled with various brands of this delicious liquid fat. People buy it because it’s supposed to be a healthy alternative to licking the fat drips on the metal grille after your softball team’s hamburger cookout. You think you’re buying pure “extra virgin” grade olive oil. It looks green – it must be. A University of California, Davis study found that a significant percentage of olive oil brands sold in the US did not meet the standards for extra virgin olive oil, with some – including expensive labels – being diluted with other vegetable oils or containing no olive oil at all. Food coloring is cheap.

Stocks are diluted too. Big companies can just print more whenever they need magic money. Robert Arnott, founder of Research Affiliates notes the importance of considering net buybacks, which factor in new share issuance alongside repurchases. In “Earnings Growth: The Two Percent Dilution,” Bernstein and Arnott show that corporate earnings growth consistently lags GDP growth by about 2% annually due to shareholder dilution from net share issuance. Contrary to popular belief, stock buybacks rarely offset this dilution, as companies issue more shares through IPOs and employee compensation than they repurchase.

Over the past two decades, several large companies—particularly in the technology sector—have engaged in significant shareholder dilution, primarily due to aggressive use of stock-based compensation. According to recent analysis, the median annual dilution rate among tech growth companies is around 2.6%, with some firms reaching as high as 8.6%.

Everybody’s favorite companies like Meta (formerly Facebook), Salesforce, Tesla, Amazon and Palantir have been cited for high dilution levels due to extensive use of Restricted Stock Units (RSUs) and stock options. These equity awards, while useful for attracting talent, increase the number of outstanding shares and reduce earnings per share. RSUs are particularly dilutive because they trigger both primary dilution (when shares vest) and secondary dilution (during tax settlement via sell-to-cover transactions).

Super Al Gore’s Lock Box

The author will now poke a bit of fun at a fellow Tennessean, whom the author respects with some reservations.

A good way to understand the arbitrary value of assets in the investable market is to imagine an invisible order – a supernatural hive mind we’ll call Super Al Gore that watches over every transaction in the markets and maintains a precise ledger of every transaction that happens. When a stock is purchased for $10.52, Super Al Gore dutifully deposits exactly $10.52 in a “lock box” for all shares of that stock. If that same share sells the same day for $10.78, they add precisely 52 cents. If the next day that share sells for 9.88, they remove 90 cents and immediately destroy it with pure Tennessee river water to produce as little carbon in the process as possible. They have been doing this for every outstanding share in the market since Al Gore launched Super Al Gore in a parallel dimension of spacetime in the year 2000.

As of July 1, 2025, Super Al Gore’s “lock box” contained approximately 62.8 trillion (62,825,048.8 million) in U.S. dollars. And that’s only the U.S. market. Super Al Gore does this for all possible markets in all possible dimensions.

At any given time, Super Al Gore may escape from their alternate dimension with the “lock box” and reunite with real Al Gore, forming the Mega Al Gore Trinity (the “lock box” is the third part, you see), who will then proceed to solve inequality, end world hunger, stop global warming, make the Internet great again and save the planet with that staggering amount of “lock box” money. With that capital in Al Gore’s hands – let’s face it – the world would definitely be saved.

Al… we’re waiting.

We like to imagine that Super Al Gore’s lock box of real money exists when we talk about the value of our equities and the total capitalization of the U.S. market — but of course, it doesn’t. Every market transaction involves a buyer and a seller. One of them is a greater fool. In the closed system of a market, money, like energy, is never created or destroyed – it’s ultimately a zero sum equation. With any traded asset abstraction, the valuation is really just a ledger of price activity – the sum of the most recent bid / ask intersection and nothing more. There’s simply no there there. It’s just a reflection of emergent price discovery that is subject to the whims of supply and demand – the sacred bid / ask convergence.

When “the market” collapses by 20,30,40% or more, we often say that “value was destroyed.” Ye gods! But that’s absurd – it was never there. The outrageous proposition of market capitalization rarely occurs to most investors, but is actually quite easy to understand: it’s utterly ludicrous to multiply the current trading price of a given asset share, unit, bitcoin or whatever by all units outstanding. If Google Class C shares are currently trading at 189.95, it does not mean that all shares of Google stock combined are worth 2.29T USD.

But we totally do, don’t we? DON’T WE!!?? Look at Super Al Gore when he’s talking to you!

In highly liquid stocks like Apple or Microsoft where there are usually plenty of buyers in a given trading session, even selling 1–2% of outstanding shares all at once could cause noticeable price disruption, resulting in rapidly diminishing returns. To trigger a 50% drop, you’d only need to overwhelm the buy-side with around 5–10% of shares in a short time frame to cascade a collapse. Just imagine what would happen if the most popular S&P500 ETF: VOO, with over 713.14 billion in assets and 2.82 billion shares, got “cancelled” because the CEO of Vanguard offended someone on the Internet.

All assets work this way – except perhaps cash – which is the intermedium of a given market, not the message. And even that gyrates on the FOREX, where standard “lots” of 100,000 units are traded at an average volume of $7.51 trillion per day. There is a natural arbitrage if you’re banking in Euros or Rupees and trade on the U.S. market in dollars. If the price appreciation of your stock increases in dollars and there was a significant change in the exchange rate, you can make extra profit if the dollar strengthened in your favor during the time you held the investment. Great success!

So when folks say, poor ol’ Warren Buffett can’t execute big trades anymore, that’s what they mean. A mega whale cruising into your harbor saying, “hey everybody, I wanna sell!” crashes all the docks, boats, buildings and people are crushed, drowned or flee in terror into the mountains.

Oops.

This vulnerability is amplified by structural inelasticity in modern markets, where passive funds and algorithmic trading dominate. These mechanisms often do not respond dynamically to price changes, meaning that when selling pressure spikes, there’s no natural counterbalance—just a vacuum. The result is a cascading effect where prices collapse not because “value” changed, but because the belief system cracked.

In short, the idea that trillions in market cap can vanish from a few percentage points of selling reveals how illusory and fragile capital appreciation is. It’s more a function of confidence and flow mechanics than any real economic foundation.

Hmm, we really don’t appreciate that kind of attitude.

So next time you look at the value of your stock portfolio, or crypto wallet, or whatever — remember that Super Al Gore doesn’t have a “lock box”. Real Al Gore is actually promoting regenerative farming practices and using his Tennessee farm, Caney Fork Farms, as a climate change laboratory, because real Al Gore — until he reunites with his transdimensional hive mind and lock box — understands that the sun, water and soil are the real magical value creation engine – which is ironically similar to an early theory of economics called Physiocracy. But don’t worry – assuming normal trading volume within a range of reasonable price volatility — if everyone continues in a calm orderly fashion, there will always be enough greater fools among us to maintain the parlay of the glorious market forever. Amen.

Aggregate Flows

So given our understanding of this quasi-ponzi, how is it exactly that everyone is going to get their money out of the market when they need it? How is it that the value of the total market index continues to go up over time, has steadily climbed for over a century, has outpaced inflation and everyone who’s dumb enough to buy a simple index fund will eventually make money? Doesn’t this prove that it works?

It’s really quite simple. There is something much like our Super Al Gore in real life: the governments and their central banking systems. The current markets are, on average, absorbing more aggregate flow of fiat currencies that are, to paraphrase Federal Reserve Chair Emeritus Ben Bernanke, “keyed into existence on a computer” by the world’s banks and wealthy investors this year than there were last year, and the year before that, and the year before that. There are more people on the planet this decade than there were last decade who like to play the green number go up magic money game on their phones.

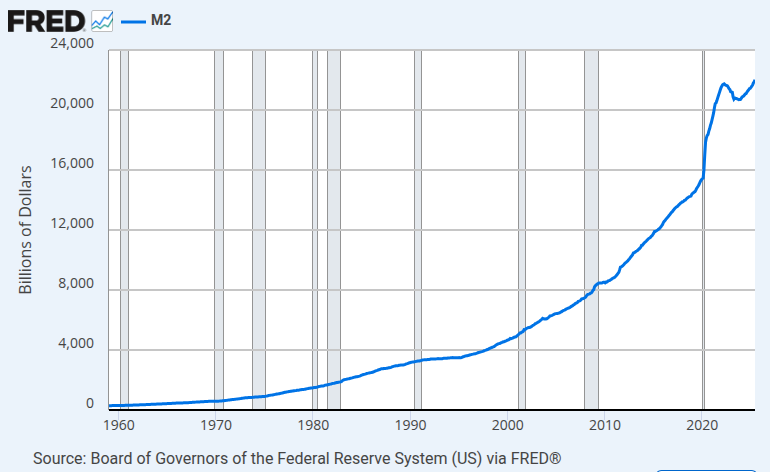

The money supply or M2 grew from 5,080 billion in 2000 to 15,467 billion in 2020. Since the pandemic stimulus, it has ballooned to 22,000 billion. That’s a 333.071% increase in cold hard super real cash money. Jerry MaGuire can see the money. Outside of taxation, bank debt collection and quantitative schemes — which decrease M2 — all the money in “circulation” and tallied on practically infinite spreadsheets and databases has to go somewhere, and the stock market is a popular place to “put it” – or should we say, pass it through (because it doesn’t stay there), especially for the ever-growing ultra-rich who have far more money than they could possibly ever spend. And those wealthy folks with sooo many money problems can then use the “equity value” of those assets for additional money creation in the form of loans and lines of credit that magically makes more and more money. As flows increase, average prices increase over time.

We can thus think of all markets and their bias for price appreciation as an “equity multiplication system” that, via the magic of price discovery, converts capital flows into a number that represents a hypothetical equity value that at some future date you may be able to convert to cash, or show to your banker or bowling buddy as proof of wealth, as long as everyone plays along and dips back into the imaginary pool just a little bit at a time.

Will the music stop? Yes, at some point. When? Nobody knows. Many times. Hopefully not today. Anyone have Al Gore’s number?

So who really won the game and has the most money? Warren Buffett won. Berkshire holds an estimated $325 billion in cash or highly liquid short term treasuries – more than the combined cash reserves of major tech companies like Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and NVIDIA. No, seriously – a nerdy kid from Omaha who still lives in a little house and eats McDonalds drive through every morning understood it was all just a game of monopoly, and he beat the pants off of everyone. Good job!

A Concluding Statement by David Graeber’s Ghost

To conclude our discussion today, I have summoned the ghost of our dear comrade, David Graeber to provide his insight on the matter. Take it away, Dave.

Thank you, Ernie.

Hmm. It strikes me as odd that investors scoff at crypto, gold, or Beanie Babies as the playground of speculators, clinging instead to the sanctity of equities—those noble shares in “real” companies, grounded in fundamentals, they insist. But isn’t this just a different mythology masquerading as prudence? Is a stock certificate any less abstract than a JPEG of a monkey in sunglasses? Is it not a sliver of imagined future cash flows, priced by algorithms chasing sentiment over substance? The valuation of a company—its “worth”—is not unlike a collective hallucination, a ritual chant of earnings projections and market multiples, all built on the assumption that tomorrow will look like today, only richer. Should investors pray to the market gods for blessings of price appreciation? Anthropologically, it’s no different from assigning divine favor to a sacred cow or a royal bloodline. The difference is that modern finance has convinced itself its gods are empirical.

“Making a market,” they say, as if conjuring a sacred space where rational actors dance to the invisible hand’s tune. But peel back the jargon and you’ll find something far more tribal: a ritualized theater of power, where brokers and bankers play priestly roles, sanctifying arbitrary valuations with spreadsheets and suits. Like the potlatch ceremonies of the Kwakiutl of the Pacific Northwest, this is less about exchange than about status—who gets to define value, who gets to destroy it, and who gets to pretend it’s all inevitable. The market isn’t born; it’s imposed, then adorned in the language of freedom. And just like ancient debt peonage, it’s the losers who are told they simply didn’t play the game right.

Finance, in its boundless ingenuity, will make a market for anything. Carbon emissions, rainfall futures, the probability of death—each sliced, diced, and repackaged into tradable units, as if the gods of liquidity demand tribute in the form of abstraction. It’s the ultimate act of sorcery: turning the unknowable into the quantifiable, the sacred into the saleable. Anthropologists once marveled at cultures that traded shells or feathers imbued with ancestral meaning; now we have derivatives on catastrophe, collateralized bundles of despair. The logic is simple: if it exists, it can be priced; if it doesn’t, invent it. Finance doesn’t just commodify—it colonizes, mapping its grid of value over every inch of human experience, until even grief has a ticker symbol.

Murray Rothbard recounts a moment when he asked Ludwig von Mises, the renowned economist of socialism, how one might definitively distinguish a socialist country from a capitalist one along the spectrum of state control. Expecting ambiguity, Rothbard was struck by Mises’s clear and immediate response: “A stock market.” Mises argued that the existence of a stock market is essential to capitalism and private property because it enables the exchange of private titles to the means of production. Without such a market, genuine private ownership of capital cannot exist. Conversely, the presence of a functioning stock market is incompatible with true socialism, which by definition abolishes private control over capital. For Mises, the stock market was not just a financial tool—it was the litmus test for economic freedom.

Von Mises’ assured response is a telling example of the kind of ideological reductionism that has long plagued economic discourse. To assert that a stock market is “crucial” to capitalism and that its mere presence precludes socialism is not only historically naive but conceptually impoverished. It reflects a worldview in which complex social arrangements are flattened into binary categories, and institutions like markets are treated as natural, self-evident features of human life rather than contingent, historically situated constructs.

The idea that the stock market represents some imagined essence of private property is absurd. Markets have existed in countless forms across cultures, many of which had no concept of “private titles to the means of production” in the modern capitalist sense. The fetishization of the stock market as the sine qua non of capitalism ignores the broader social relations—debt, labor, hierarchy, and violence—that underpin capitalist systems. It also conveniently erases the fact that many so-called socialist countries have operated stock exchanges, often as mechanisms of state planning or hybrid ownership models. The Soviet Union, for example, had forms of internal capital allocation that mimicked market behavior, and contemporary China maintains a robust stock market while retaining centralized control over key sectors.

Moreover, Mises’s claim reveals a deeper ideological commitment to property as a moral absolute, rather than a social convention. But property is not a thing—it is a relationship, a set of understandings about who gets to do what with which resources. To reduce socialism to the absence of a stock market is to ignore the lived realities of people who have experimented with cooperative ownership, mutual aid, and democratic control of resources—often in ways that defy both capitalist and statist paradigms.

Mises’s “decisiveness” is less a triumph of clarity than a symptom of intellectual rigidity. Real economic systems are messy, pluralistic, and shaped by human values and struggles. The stock market is not a litmus test for freedom—it is a mechanism for speculation, extraction, and the abstraction of human labor into digits on a screen. To confuse that with liberty is to mistake the map for the territory.

The stock market, for all its pomp and ceremony, is less a wealth-generating system than a glorified confidence game—an elaborate theater of abstraction where numbers masquerade as assets and speculation is sold as productivity. It thrives not on innovation or value creation, but on the relentless recycling of belief, where the illusion of wealth is sustained by a game of greater fools. We are told this is capitalism’s crowning achievement, yet it produces nothing, consumes everything, and redistributes capital upward through mechanisms so opaque they border on mystical. In truth, the market is a monument to financial nihilism—a place where value is untethered from reality, and the only thing growing is the distance between what we pretend to own and what actually exists.

Thank you, David. We miss you, brother.

Now, everyone go home and invest in the market. If you’re trying to build wealth, it’s still the best game in town. Al Gore has a booth in the lobby with brochures.