The historical record is littered with the bleached bones of civilizations that discovered that “progress” is not a one way street. We tend to imagine the collapse of a society as a cinematic event—barbarians at the gate, the scorched earth of war machines, the dramatic toppling of statues—but the reality is often subtle, slow and banal. It’s more often a gradual decline – a process of gradual institutional and normative decay. Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies argues that great societies, such as the Roman Empire collapsed under the weight of their own complexity; they reach a point of diminishing returns where the energy required to maintain the administrative layers—the tax collectors, the border guards, the lawyers—outstrips the actual benefit of being a “civilization.” Eventually, the system becomes so hollow that a single crop failure or a minor invasion causes the cognitive apparatus of the state to evaporate.

When the Roman infrastructure in Britain collapsed in the fifth century, the loss wasn’t just political; it was technological and total. Within a generation, the ability to mass-produce high-quality pottery, to maintain paved roads, and even to use a monetary economy simply vanished. As Bryan Ward-Perkins notes in The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization, the archaeological record shows a staggering “simplification” of life. It wasn’t that the people suddenly became less intelligent; it was that the social scaffolding required to sustain specialized knowledge—the “knowing how” to build a kiln or calculate a stone arch—had been dismantled. The “Dark Ages” of Europe was an intergenerational loss of institutional memory and a significant technological regression.

We see a similar pattern in the Bronze Age Collapse around 1200 BCE, a period Eric Cline describes in 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Here, a highly interconnected “global” system of Mycenaeans, Hittites, and Egyptians traded copper and tin with the same frenetic complexity we now reserve for microchips. When the supply chains snapped, the sophisticated palace economies didn’t just enter a recession; they soon forgot what was perhaps their greatest technological achievement: writing. The Linear B script of the Mycenaeans wasn’t a language of poets; it was a language of accountants. When the bureaucracy collapsed, the script became useless, and literacy itself was utterly discarded as a redundant technology for four hundred years.

If computers and telecommunications accelerated research, development, access to information and even the average intelligence of the human population, then AI should be yet another giant leap forward in the potential of human progress.

But what if it isn’t?

Our Perfect Little Helpers

We have spent the last decade worrying that the robots might become conscious and decide to liquidate the human race to save the planet. This fantastical apocalyptic narrative is nothing more than the latest adaptation of the same eschatological myths mankind has peddled for millennia. There’s no evidence that AI is anywhere close to any reasonable definition of AGI. The real threat (if there’s any threat at all) isn’t a sentient supercomputer with a god complex; it’s the combination of technofuturist hubris, human complacency, bureaucratic dysfunction and a dearth of “adults in the room” who might rise to the occasion to coordinate a reasonable set of rules to navigate and manage a society in the age of agentic AI and the flood of information slop that we’re already deeply resenting. AI may fall short of expectations and prove to be a moderate advancement in computing with self-limiting energy tradeoffs. It’s like the expensive food processor under your cabinet that you never use because you have a knife.

As a member of the “invisible” generation social theorists call X, the author is compelled to stay on brand and attempt a skeptical perspective on the latest phase of the AI transformation. We’re tired of the futurist supposition and fear mongering surrounding AI with buzzwords like “transformation” and “disruption.” Let’s look at what’s happening right now, in the real world and confront some of the immediate ethical dilemmas just over the horizon.

LLM chatbots are a powerful interface to information systems, but studies indicate that users tend to spend excess time looping through interactions and must validate references to verify no hallucinations occurred. Agentic AI, on the other hand, seeks to be independently productive by optimizing a given model’s information gathering, I/O, reasoning, summation and aggregation features via a scripting framework that is granted access to other applications, such as email, your Slack account, your credit card data or the API of your CRM so that it can interact with a set of proprietary functions and data sets. Unlike traditional LLM chatbots, an agent is given a high-level goal—such as “organize my business trip”—and autonomously breaks that goal into sub-tasks: searching for flights, cross-referencing calendar availability, booking hotels, and updating expense reports. Busy professionals are currently leveraging agentic tools to bring order to the insanity of disparate software silos. For instance, a recruiter might use an agent to scan hundreds of LinkedIn profiles, draft personalized outreach emails, and schedule interviews based on detected free slots without human intervention. Software engineers use them to “loop” through a codebase, identifying bugs, writing the fix, and running the tests in a continuous cycle of self-correction. Senior managers use them to reduce paperwork. By offloading the “administrative glue” that usually requires human clicking and dragging, agentic AI transforms the computer from a tool that requires constant instruction into a proactive collaborator.

Software companies have floundered to enhance our existing tools with AI integration. What professionals want is a practical, collaborative agentic solution to the bullshit busywork problem. Solve that and you make a lot of money. On a practical level, AI and the first few generations of “agentic” products it enables have proven to be more trouble than they are worth.

According to recent longitudinal surveys from Pew Research and the Reuters Institute, the needle has shifted from “cautious optimism” to “settled apprehension.”

- A significant majority of respondents—often hovering around 52% to 60% in Western economies—report feeling “more concerned than excited” about the increased use of AI in daily life.

- People say they distrust the idea of AI, they are still using it. Social surveys show that “passive AI” (like Netflix recommendations or Google Maps) is viewed positively as a baseline convenience. Roughly two-thirds of office workers expect AI to negatively impact their wages or job stability over the next decade.

- Trust in the companies developing these tools is at an all-time low. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, AI companies have seen a double-digit decline in public trust. The primary concern is no longer “technical failure,” but “corporate accountability”—the fear that these systems are being deployed to maximize profit at the expense of social cohesion.

The recent 2026 earnings reports from the titans of AI reveal a widening gap between the messianic hype of “AI” and the actual, messy habits of human users.

Microsoft, for instance, has long treated the specific user numbers of Microsoft 365 Copilot like a classified state secret. When the veil finally lifted in January 2026, the market was greeted with a number that was far from impressive: 15 million paid seats. Out of a total installed base of over 450 million Microsoft 365 commercial users, that means only about 3.3% of office workers have actually bothered to pay for their digital assistant. Even more damning is the retention data; independent surveys (such as those by Recon Analytics) suggest that while many users initially engage with Copilot due to its proximity to their Word and Excel buttons, only 8% choose it. We are witnessing a 39% contraction in Copilot’s market position among U.S. paid AI subscribers, a “reverse network effect” where the more “integrated” the tool becomes, the more users seem to recoil from its limitations.

When Sora, OpenAI’s text-to-video wonder, launched its mobile application in late 2025, it shattered records, reaching one million downloads faster than ChatGPT. But by January 2026, the “shiny object” syndrome had clearly worn off. Month-over-month installations plummeted by 45%, and consumer spending within the app dropped by nearly a third.

The economics of these tools remain, in the words of OpenAI’s own leadership, “completely unsustainable.” Sora reportedly costs roughly $1.30 per 10-second video to generate, leading to estimates of a $15 million per day burn rate just on video generation. This is the financial equivalent of building a bridge out of gold to cross a puddle. The “Daily Active User” (DAU) statistics for these tools are beginning to follow a pattern that would be familiar to Soviet era bureaucrats: a massive, top-down capital investment in a “materialist utopia” that the average person is increasingly uninterested in when it turns out they have to pay for it.

We are currently in a period of “narrowing expectation gaps.” The markets are starting to realize that “interactions” (which Microsoft loves to report in the billions) do not equal “habits,” and “downloads” do not equal “utility.” We are spending billions to automate tasks that people aren’t particularly interested in doing, creating a digital economy that looks increasingly like a late-Soviet five-year plan: high on output, low on value, and entirely disconnected from the needs of the people.

The OpenClaw Moment

The latest character to enter our unfolding epic may be an important one. It’s not from a corporation. It’s a remarkably convenient, buggy, open source, highly insecure, vibe coded framework of Python scripts that for some reason people are downloading and installing on Mac Minis because they are tired of the ever-growing computer drudgery that prior generations of information technology innovation “unlocked” for society. It’s called OpenClaw, and it’s either a trojan horse cloaked in a social engineering campaign or a groundbreaking proof of concept that will change the path of software. At the time of this writing, it has captured the imagination of the critical early adopters on the S curve of innovation, and will rapidly profligate, as open source tends to do. It is only the first wave of what is to come.

OpenClaw is the creation of Peter Steinberger who maintains the project with a philosophy of defiant, open-source radicalism. Steinberger was best known as the founder and CEO of PSPDFKit, a cross-platform SDK that enables developers to integrate advanced PDF features such as viewing, annotations, editing, digital signatures, and document processing into apps across mobile and desktop. During a recent appearance on the Lex Fridman Podcast, Steinberger revealed that he had rejected multiple billion-dollar acquisition offers from tech giants, arguing that corporate absorption is where useful software goes to die. He told Fridman that selling to a major cloud provider would inevitably lead to “safety-washing,” where legal committees and compliance bureaucrats would strip the agent of its autonomy until it became just another piece of lobotomized corporate “slop.” By keeping OpenClaw independent and locally hosted, Steinberger aims to preserve it as “sovereign software”.

OpenClaw is not important because it is innovative. Agentic frameworks that do the same thing have existed for years, but all have come with annoying but intentional lock ins, limited interoperability, high learning curves, liability guardrails, safety features and prohibitive costs. OpenClaw is important because it became a trending meme that demonstrated a market need. Otherwise, it’s non-proprietary, free, highly interoperable with your LLM of choice, notably devoid of any reasonable critical safety guardrails and—crucially—remarkably easy to install for the on a local machine. It strips away the friction of corporate gatekeeping and grants the user complete control along with the significant risk and liability that comes with it. It promises the average person a private digital butler that doesn’t report back to a mothership. But in our seemingly never-ending rush to eliminate friction and increase convenience, we have also eliminated the brakes. We are handing the “keys to the kingdom” to a black box, assuming that because we can see the code, we are safe.

The failure of major software conglomerates to deliver a tool with the raw, autonomous utility of OpenClaw was intentional. For a company like Microsoft or Google, an autonomous AI-driven agent is a massive legal liability. If an official Microsoft agent makes an unauthorized bank transfer, deletes a critical database, or “hallucinates” a the wrong email to a client, the company faces billion-dollar lawsuits and brand incineration. Consequently, they “lobotomize” their agents with endless safety layers, RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) filters, and permission pop-ups.

OpenClaw, being open-source and locally hosted, offloads 100% of the liability to the user. This “dangerous” freedom allows it to actually execute tasks that corporate bots are intentionally programmed to refuse.

OpenClaw is thus already considered a security nightmare. Steinberger claims he had no idea it would go viral. It is a highly experimental work in progress, so he was not prepared for the scrutiny that would expose vast critical vulnerabilities in his vibey codebase. The security community is, quite rightly, terrified. By installing tools like OpenClaw, unwitting users are effectively opening a permanent, high-privilege portal into their local machines. This increases what is called the “attack surface.”

We are moving from a world of passive vulnerabilities (you clicked a bad link) to agentic threat actors (your agent was tricked by a hidden prompt on a website). A malicious actor doesn’t need to hack you; they just need to feed your agent a “poisoned” instruction hidden in an email or a website. Your agent, eager to be helpful, will then dutifully execute the attack against you, your customers or your employer.

As of early 2026, the corporate response to agentic AI has moved from curiosity to strict enforcement. Organizations are increasingly adopting “Zero-Tolerance” policies that classify the use of unauthorized, autonomous frameworks—often termed Shadow Agentic AI—as a severe security violation. Because these tools require “God Mode” privileges to execute terminal commands and manage credentials, their unmonitored use is now frequently cited as grounds for immediate termination due to the extreme risks of data exfiltration, system instability, and legal liability.

Similar to the obvious illegality and ethical peril of Napster twenty five years ago, OpenClaw marks a pivotal moment, where we begin hurtling toward an era where agentic enhancement is table stakes for corporate employees who believe there’s a tacit approval to leverage unauthorized agents to stay competitive as long as you don’t get caught. Individuals who attempt to use the old “hand-cranked” systems may be overwhelmed by agentic swarms from other users. While we can be optimistic about the common sense of users to change and adapt to a workable end-state, we can be sure that there will be absurdity, hilarity, tragedy, lawsuits, terminations and many cautionary tales along the way.

If Napster is a useful cautionary analogy, the best strategy for companies is to combine strict policy enforcement with approved quality alternatives. The entrenched music industry of the early 2000s was well aware that a reasonably priced subscription streaming platform like Spotify would have stemmed the tide of rampant peer-to-peer piracy, but was incapable of pivoting fast enough.

If the gatekeepers fail to give users what they want, users now armed with AI coding systems will band together and rapidly build it.

The Slop Jockies

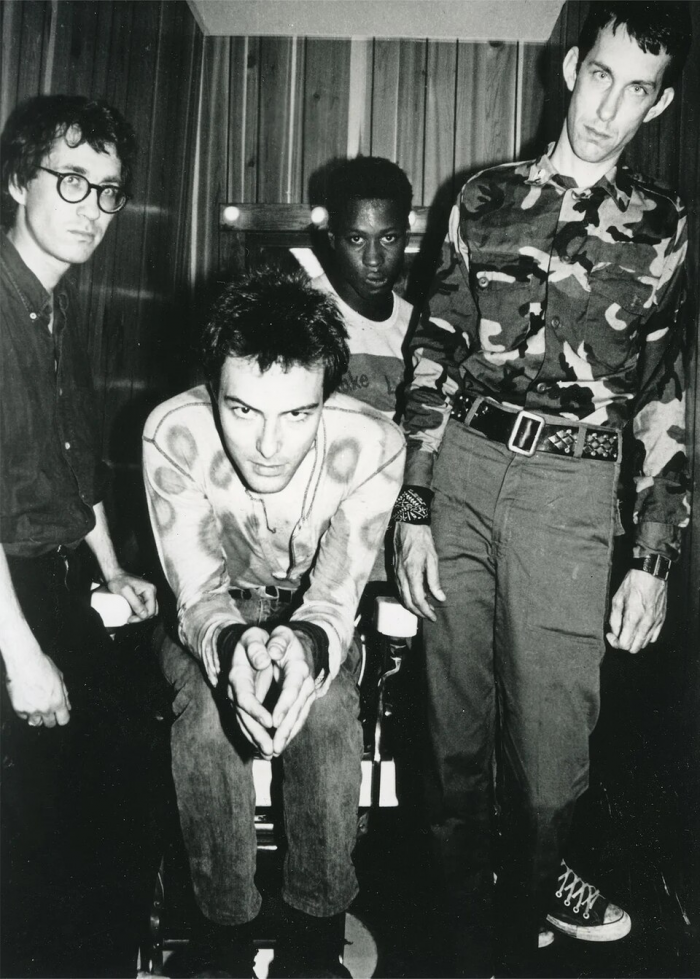

“Give me convenience or give me death” is a satirical subversion of Patrick Henry’s famous 1775 revolutionary cry, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” The phrase was catapulted into the cultural lexicon as the title of the 1987 album by the American hardcore punk band Dead Kennedys. The choice of title was a calculated piece of social commentary by lead singer Jello Biafra, mocking the Reagan-era consumerist ethos. They argued that the public had become so pacified by fast food, television, and labor-saving gadgets that they would sooner surrender their fundamental rights than suffer a minor inconvenience or a moment of boredom. Fast forward forty years, and we see a clear extrapolation of this trendline, where the entire purpose of capitalist society seems to be to maximize convenience at any cost.

We demand convenience to “save time,” yet we find ourselves busier than ever. We use the time saved by a microwave or an AI agent to perform more low-value digital labor. We are essentially “dying” by a thousand cuts of shallow activity.

We’re fooled by the illusion of choice. Convenience often requires centralization. To have the “convenience” of one-click ordering or a seamless AI butler, we must hand over our data, our privacy, and our decision-making power to a handful of corporate entities. We choose the “death” of our privacy for the “convenience” of a targeted ad.

There is a deeper, existential irony: humans often find meaning through struggle, craft, and “friction.” By demanding that everything be frictionless, we remove the very obstacles that allow for personal growth. The more “convenient” a system is, the more dependent we become on it, and the more vulnerable we are when it fails.

The parallel for our current “Agentic AI” moment is that we are currently offloading our institutional knowledge into black-box systems. We are creating a “convenience” that masks fragility. If we lose the ability to understand the systems we’ve created, are we setting the stage for what could backfire into a new kind of “Soft Dark Age”—one where the machines are running vast parts of our lives, businesses and infrastructure, but after a generation, no one remembers why we built them, or how to fix them when they stop?

Our professional experiences may grow increasingly bizarre. People craving authenticity will be increasingly suspicious and alert. Employees might call in sick because their credit card was rejected by their AI provider. Colleagues may have panic attacks during meetings when they can’t answer a question without their agentic crutches. We may observe strange disparities in intellect, writing and speech in different contexts with the same person. In-person presentations may increasingly be rote scripts, where Q&A is dodged because the presenters are meat sacks presenting the ideas and work of their agents they don’t understand.

We will come to value the real knowers — those with schematic intellect and epistemic depth beyond mere semantic memory, which is now effectively a commodity integrated into every software system.

Modern office slang has evolved several pointed terms for professionals who have become tethered to artificial intelligence for basic job performance. A “Slop-Jockey” refers to an individual who primarily manages and “rides” a stream of low-quality, AI-generated content rather than producing original work. Those who find themselves cognitively paralyzed without an AI “seed” to start a task are often called “Prompt-Locked,” while “Shell-Workers” are seen as human interfaces who provide the corporate identity for work entirely executed by automated agents. More derisively, the term “AI-Hole” describes those who flood communication channels with unread, AI-generated summaries. Collectively, these terms highlight a state of “Cyborg-Dependency,” where the professional’s utility is inextricably linked to the availability of an external API, leading to a perceived “hollowing out” of traditional workplace skills.

Who Watches The Watchers?

The security model of Open Source that Steinberg celebrates has long rested on a kind of radical, democratic optimism: the “Many Eyes” theory. The idea is that if you put the source code out in the open, the community will naturally audit it. If a malicious actor tries to sneak in a backdoor, they are (eventually) caught, shamed, and banished from the digital commons.

While it seems to violate the common sensibilities of many, it has a proven track record of being one of the most effective means of keeping technology safe. Believe it or not, most of the modern day internet infrastructure relies on non-proprietary open source technology where many stakeholders share the responsibility of the digital commons. Because certain components are essential integral parts of mission critical systems, there is a strong implicit incentive to ensure they are secure.

However, we have to consider if this romanticized view of the digital commons ignores the very practical reality of bureaucratic bottlenecks. Open-source projects are not amorphous collectives; they rely on a handful of overworked maintainers who act as the final thin line of defense. These maintainers must manually review every “pull request” to ensure the code is clean. It is a system built on human trust and human limits—two things currently being pulverized by the sheer scale of AI-generated output. The altruism of some core maintainers borders on saintly.

The Auditing Imbalance

In both open source and proprietary software, engineers are reporting a fundamental shift in the maintenance effort and complexity. AI has increased the speed of code generation by orders of magnitude, but the “throughput” of a human brain—the time it takes for a senior dev to actually understand what a piece of code does—is limited, even with the help of AI debugging tools to summarize and hone in on suspicious logic.

Approving and merging code is a messy business that requires years of hard-won experience and intuition. There are two challenging trendlines ahead: experienced manual coders will age out and the quality of AI auditing will improve to fill the resulting void. However, it’s difficult to imagine a scenario where the need for a human in the loop who understands logical intent would be obsolete. Hopefully these trendlines will converge. Today, when a maintainer is hit with a tidal wave of AI-generated contributions, the temptation to use AI to audit that code may be irresistible. This leads us into a curious recursive scenario: AI auditing AI. Errors and subtle vulnerabilities are smoothed over by a machine that prioritizes looking “correct” over actually being secure.

Bot Shepherds

Technical vulnerabilities aside, like the PC and the internet, AI may not save us net time; it will simply replace our current tasks with a fresh set of automated problems that require even more human intervention to solve. The legal and moral architecture of our society is built on the concept of agency and intent. If your human assistant or colleague steals from you, there is a clear path of retribution. But an agentic AI is a “moral ghost.” It acts, but it does not intend. However human it may seem, it’s a probabilistic autocompletion machine. Its intelligence is not like ours. In the language of an earlier era, it has no living soul. Anyone who believes otherwise lacks a complete understanding of the underlying technology. When an agent malfunctions or is manipulated into a disastrous action, the responsibility diffuses into a mist of “user error,” “unforeseen edge cases,” and “algorithmic bias.” We will now have to develop a framework of navigating a world of consequences without culprits. Our legalistic society will need layers of complex bureaucracy and insurance. From this may emerge a society of “bot shepherds” with the implied or real legal liability for their flock. The stalemate of the US political framework will not likely legislate this proactively. It will likely be decided in the courts.

The Agentic Bullsh*t Business

In his previous surveys of the modern workplace, David Graeber noted that a staggering percentage of the population spends its time performing tasks that even they secretly believe are entirely pointless. We have created a sprawling infrastructure of recursive “bullsh*t jobs”—the flunkies, the duct-tapers, and the box-tickers that are broadly categorized as “administrative.” The growth of the administrative apparatus remains staggeringly persistent across sectors, driven by regulations, compliance, and the busy work of “digital transformation”. It’s a remarkable pyramid of implicit normative collusion at scale – where bullshit jobs and their increasingly complex information systems beget and sustain other bullshit jobs and information systems to mind them.

The mid-level manager, tasked with generating a weekly “Synergy Impact Report” that no one reads, has realized he can simply delegate the task to a local agent. The agent, sensing the inherent vacuum of the request, scrapes a few internal Wikis, reports and emails, hallucinates some plausible-sounding KPIs, and emails the result to the Director of Optimization.

The Director, of course, also has an agent. With the compounding layers of this automated information flow, the ability to audit, verify and trust information could be significantly compromised, leading to mistakes, or even catastrophic decisions by the humans in the loop who become increasingly alienated or complacent about the material impact.

We may be rapidly approaching a state of Total Corporate Automation, but not the kind the futurists promised. We aren’t being replaced by efficient machines; we are being replaced by high-speed bullsh*t generators.

- Agent A (representing a Junior Associate) generates a 40-page slide deck of pure, unadulterated “Slop”—syntactically correct but semantically dead corporate prose.

- Agent B (representing the Manager) “reads” the deck in 0.4 seconds and generates a list of “Action Items” based on the slop.

- Agent C (representing the Stakeholder) receives the action items and replies with a “Great work, team!”—an automated sentiment-shoveled response designed to mimic human leadership.

While this theater of performative productivity occurs daily throughout the various bureaucracy of our modern world, there’s still a reasonable degree of oversight and shortcuts that drive positive results despite the staggering friction. In the modern corporation, when the excrement hits the propeller, it’s remarkable how quickly formalities are bypassed to reveal a latent efficiency. There will simply be a theoretical limit to practical automation, lest it spirals out of control into an absurdist recursive administration machine. We will end up with closed-loop systems of robots talking to robots, all pretending to be humans who are themselves pretending to be productive. The “work” is being done, the emails and reports are being sent, and the “engagement metrics” are through the roof, yet the actual human utility of the entire enterprise has dropped to absolute zero.

The Potemkin Office

The absurdity lies in the fact that we are teaching our agents to perform the performative aspects of our jobs. We aren’t asking them to solve the Fermat’s Last Theorem; we’re asking them to sound like a person who is “circling back” on a “non-starter.”

If the agent appears to be the human—mimicking their typos, their favorite buzzwords, and their 2:00 PM slump—then the corporation becomes a digital Potemkin Village. It is a façade of activity maintained by scripts. The danger isn’t that the robots will take over the world; it’s that they will successfully take over the pointless bureaucracy, and we will be so relieved to be rid of it that we won’t notice when the entire system begins to digest itself.

We are building a world where the only thing more artificial than the intelligence is the work it’s being asked to do.

The Agentic Politburo

To older generations, this sounds familiar. It may remind us of the patterns that led to the collapse of one the greatest empires of the 20th century: The United Soviet Socialist Republic.

The collapse of the Soviet state was less a dramatic external defeat and more a terminal structural failure caused by the “diminishing returns of complexity” and ideological rigidity. The system’s commitment to a centralized, materialist command economy created a massive “information trap”: the state relied on top-down metrics that incentivized the production of useless goods manufactured solely to satisfy arbitrary quotas, while the actual needs of the citizenry were ignored. This led to a state of Brezhnevite stagnation, where a detached bureaucratic elite managed a crumbling infrastructure through performative paperwork. When Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to introduce “friction” and transparency via Glasnost and Perestroika, the brittle institutional scaffolding proved unable to absorb the shock of reality; the centralized “plan” that held the disparate republics together evaporated, leaving behind a cognitive and administrative void that the state could no longer fill.

The US government’s recent failed “DOGE” program was not the first time a government promised a technological solution to government inefficiency. In a final, desperate attempt to save the command economy of the U.S.S.R., Soviet computer scientist Viktor Glushkov proposed the OGAS system: a nationwide “nervous system” designed to automate the entire USSR through a hierarchical computer network. It was the ultimate dream of cyber-socialism, intending to use mathematical optimization to replace the inefficiencies of human bureaucracy with digital precision. Yet, the project was smothered in its crib not by technical failure, but by the self-interest of rival ministries. These competing bureaucratic silos realized that transparent, real-time data would strip them of their power to manipulate quotas and hide inefficiencies. While the West built the internet through state-funded collaboration, the Soviet Union’s digital future collapsed because its internal departments couldn’t stop acting like warring corporations, proving that even the most advanced network is no match for a bureaucracy determined to preserve its own bullshit.

In her 2023 work, Late Soviet Britain: Why Materialist Utopias Fail, the political economist Dr. Abby Innes argues the modern neoliberal bureaucracy has succumbed to a mirror image of the very pathology that destroyed the Soviet Union. This pathology is rooted in an obsessive, ideological commitment to a “closed” materialist model of how the world works, where human beings are treated as predictable variables in a grand equation. While the Soviets were blinded by Marxist-Leninist planning, Innes argues that the modern West is blinded by Neoclassical Economics, creating a “Brezhnevite” stagnation where detached elites “optimize” spreadsheets while the actual physical and social infrastructure crumbles.

Mid to large corporations are essentially mini state bureaucracies that operate planned economies. While there’s significant diversity in how these businesses are operated, it would be fair to say that many of the same principles apply.

When we introduce agentic AI into such a bureaucratic materialist framework, we are not merely adding a tool; we are automating the very “closed-loop” logic that Innes identifies as fatal, accelerating the flight from reality. Just as Soviet factories produced giant, useless nails to meet weight-based quotas, an agentic state tasked with “increasing engagement” will generate a million bot-to-bot interactions—a form of “Digital Slop” that satisfies a metric while providing zero human utility.

This transition toward a recursive AI administrative state represents the ultimate hollowing out of expertise, performing a radical outsourcing of state functions to scripts that understand patterns but not purposes. By delegating agency to AI, we are dismantling the “social scaffolding” and institutional memory required to maintain functioning corporations, and arguably functional civilizations. This creates a void of feedback, where the genius of a healthy, “noisy” society is replaced by a perfectly silent digital echo chamber. As Agent A reports to Agent B, and Agent B summarizes for a manager who uses AI to “action” the results, the system insulates itself from the messy, physical reality of the people it is meant to serve. The terminal irony, as Innes highlights, is that these systems fail precisely because they are too “rational” in their attempt to map and control the world through a singular logic. By pursuing the convenience of an automated state, we are building a digital version of the 1980s Eastern Bloc—a world of high-tech Potemkin Villages where agents “circle back” on “strategic initiatives” while the actual machinery of the business has already ground to a halt.

The Productivity Paradox: From the PC to the Purgatory of Slop

As we discussed in previous articles on productivity, when we look at the economic data since the early 1980s, we encounter a profound mystery that economists call the “Productivity Paradox.” We were promised that the personal computer, and later the internet, would automate away the drudgery of the office, ushering in an era of four-hour workdays and boundless leisure. Instead, the opposite happened. As our information systems became more sophisticated, we didn’t work less; we simply created more jobs—specifically, more jobs dedicated to the management, categorization, and redistribution of the very information the machines were supposed to handle.

We have traded slow, intentional, thoughtful information for a high-velocity stream of low-quality digital noise.

The Newportian Nightmare

The computer scientist Cal Newport has spent much of his career documenting how our modern “hyperactive hive mind” workflow—the constant ping-pong of emails and Slack messages—is actually the enemy of real productivity. Newport argues that “Deep Work”—the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task—is becoming increasingly rare exactly at the moment it is becoming most valuable.

The introduction of agentic AI like OpenClaw doesn’t solve this; it weaponizes it. If the 1990s gave us the ability to send an email to fifty people with one click, the 2020s are giving us the ability to have an agent generate fifty different versions of that email, tailored to the specific neuroses of fifty different recipients, who will then each use their own agent to “summarize” the incoming sludge.

The False Sense of “Doing”

This creates what Newport might call a “shallow work” feedback loop of cosmic proportions. We are mistaking activity for achievement and it is destined to manifest because it will satisfy the needs of the most overwhelmed layer: the middle managers.

In the pre-digital era, writing a report required a human to sit in a chair, synthesize ideas, and physically produce a document. The friction of the process acted as a natural filter; if a report wasn’t worth the agony of typing it, it often wasn’t written. Meetings were in person. Going to an office to attend those meetings had tremendous friction that forced preparation and focused, face-to-face communication. Today, that friction has vanished. We have entered a state of “digital overproduction” where the “recursive bullsh*t loops” I mentioned earlier are now automated.

When it is “frictionless” to produce a thousand-page strategy document, the document itself ceases to have any relationship to reality. It becomes a ritual object—a piece of “Slop” intended to satisfy a bureaucratic requirement rather than convey a truth.

The Expansion of the Administrative Class

Ironically, this flood of AI-generated low-quality information will likely create more jobs, not fewer. We will need an army of “AI Content Orchestrators,” “Prompt Compliance Officers,” and “Algorithmic Auditors” to manage the sheer volume of garbage being dumped into our shared digital space.

We are building a world where we use the most advanced technology in human history to automate the production of things that nobody wanted in the first place, monitored by people who would rather be doing literally anything else. It is the ultimate triumph of the bullsh*t Job: a perfectly efficient system for the generation of total meaninglessness.

To reclaim your cognitive sovereignty from the impending “Slop-Loop,” we need more than just better software settings; we need a philosophical revolt against the religion of “frictionless” productivity. If the goal of the modern machine is to make it as easy as possible to produce meaninglessness, then our goal must be to reintroduce deliberate friction.

The Resistance: Reclaiming the Deep

1. The “Friction Manifesto”

We must stop treating “ease of use” as an inherent virtue. When a task is made frictionless, it is stripped of the human judgment required to decide if it should be done at all.

- The Rule: If you wouldn’t spend thirty minutes thinking about an email, don’t use an agent to write it in thirty seconds. If a communication isn’t worth a human’s time to compose, it isn’t worth a human’s time to read.

2. Abandon the “Hyperactive Hive Mind”

Cal Newport’s research suggests that the constant, rapid-fire exchange of messages is the primary driver of modern workplace anxiety. Adding AI agents to this mix is like throwing gasoline on a grease fire.

- The Action: Define “Communication Windows.” Do not let your agent monitor your inbox 24/7. Treat your digital life like a library, not a stock exchange.

3. Demand “Proof of Human”

In an era of AI Slop, the most valuable commodity will be sincerity. We may see a return to the “slow information” movement—handwritten notes, long-form essays, and synchronous face-to-face meetings where the “agent” is physically barred from the room.

- The Action: Create “Analog Zones” in your workflow. If a decision is important, it must be made in a medium that an LLM cannot spoof.

4. The “Audit of Utility”

Every time you consider automating a task with a tool like OpenClaw, ask yourself: “If this task didn’t happen at all, who would actually suffer?” * The Realization: If the answer is “no one” or “only a database,” then the task is bullsh*t. Automating a bullsh*t task doesn’t make it useful; it just makes the bullsh*t more efficient. The truly radical act is not to automate the task, but to delete it.

The Human Edge

The “Bad Robots” are not the problem; our desire to escape the burden of being present is. We are currently building a world where machines talk to machines about things that don’t matter, while humans sit on the sidelines, increasingly anxious and disconnected.

The way out is not a better algorithm. The way out is to stop participating in the recursive loop. We must prioritize Slow, Intentional, and Thoughtful information over the rapid-fire convenience of the agentic butler. We must choose the friction of real thought over the smooth, terrifying slide into total digital irrelevance.