I’m hesitant to write about the pop culture of my youth, especially an album that received such universal acclaim and has been so exhaustively analyzed. It’s impossible for me to reflect on my experiences in the 1980s objectively, as my mind was still blooming, my childhood was happy and my future optimistic. But I do have the vantage point of closely observing 36 years of audio production trends as both a fan and recording engineer. I can look back on U2‘s “With Or Without You” and “The Joshua Tree” album and ask, “was a single that gave me goosebumps and butterflies when I was twelve years old really that good in the broader context of the pop music canon and if so, why?”

When “The Joshua Tree” was released in 1987, the channels of communication and distribution were still unified, limited and homogeneous, where the popular culture industry in the United States operating via live analog broadcasting offered the possibility of a shared collective experience — a peak moment in the zeitgeist. Something as trivial as a major label pop song could be played on FM radio or MTV and in the back of your mind you knew that thousands, or even millions of souls were also experiencing it at the same time. Even today I find live radio slightly more exciting than streaming, even when a streaming release is brand new, or the song or video is “debuted” on a live stream. “With Or Without You” was a monumental release in the spring of that year where a substantial portion of the world stopped what they were doing, and shared an experience of something beautiful and highly unusual. Do you remember hearing that song for the first time?

Popular music in the mid 80s was typically big, melodic, lighthearted and optimistic. From an audio production perspective, mixes were drenched in glossy digital reverbs, big gated kick and snare drums boomed, drum machines and electronic drums offered new percussive sounds, modern innovations in synthesizers and computer controlled sequencing offered a broad new palette for keyboardists and producers to work with and added a futuristic sheen to everything, and Solid State Logic’s computer automated mixing desks offered unprecedented control over the balance and movement of a mix. The style was bigger than life: it was optimistic hyper-realism. The music of the mid-80s in particular hit a high point of “big production” where every genre of music sounded dramatically distinct from a decade before, from rock to pop to country. Listening to the top 40 singles of 1975 vs 1985 reveals a fairly stunning shift of mode. Everything had to have that “big sound.”

But lurking in the lower rankings of the various charts during this era of glossy production hegemony were acts that eschewed this aesthetic. There was a time in the early 80s when the Irish band U2 was not the global pop rock juggernaut they would gradually become, but just another scrappy post-punk angular guitar band from “across the pond,” usually lumped in with acts like XTC, Magazine, Souixie & The Banshees, Simple Minds, Big Country, The Psychedelic Furs, Ultravox and others whose music rarely made a dent in the US market outside of high school and college hipsters who tuned into college radio stations or stayed up late to watch (and videotape) MTVs alternative music show “120 Minutes.”

But by 1986, U2 had reached a critical inflection point in their career. They had produced a landmark and critically well-received album, “The Unforgettable Fire” with the prominent production team Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois that also yielded an unexpected US hit with, “Pride (In The Name Of Love)” peaking at 33 on the US Billboard Hot 100 and number 2 on the US Billboard Top Rock Tracks. The band had featured prominently with a memorable performance in the globally televised Live Aid concert in 1985 and the Amnesty International Conspiracy Of Hope tour in 1986, performing alongside such eminent heavyweights as Sting and Peter Gabriel. U2 had established a foothold on the ladder of cultural relevance and had been gradually creeping into the public consciousness thanks to MTV. Critics and tastemakers knew that U2 was unique and had the potential to do something big. Expectations were high.

The standard major label A&R development playbook at the time would have pulled in a major pop producer and potentially ghost writers to help a band smooth out the rough edges and craft a catchy predictable smash hit in the mode of the day that would appeal to the average US listener. However, the U2 organization, including an already successful touring operation managed by Paul McGuiness and Chris Blackwell’s Island Records wasn’t your average industry arrangement. This was still the golden age of labels investing large sums into the long term development of promising artists. Starting as a label that was instrumental in bringing Jamaican Reggae to the UK and US markets, Blackwell’s business had a reputation for taking risks and was financially betting big on U2 as their roster’s flagship and the next album selling better than “The Unforgettable Fire” to help the label stay solvent.

It’s in this context that we have to look back on why “The Joshua Tree” and its subsequent impact over the next decade was so unusual and pivotal. In 1986, anyone could have predicted that U2‘s next record was going to chart and sell reasonably well, but nobody could have guessed that such an atypical recording would go on to be one of the most successful albums of all time and sell 25 million units and counting.

It’s difficult to appreciate now, but from an audio production standpoint, almost everything about “With Or Without You” as the lead single was antithetical to the prevailing norms of 1987. U2‘s catalog up to 1984‘s “The Unforgettable Fire” was marked by an experimental but understated production style that consistently and honestly captured the band’s live sound in a studio setting — typically at Windmill Lane studios in Dublin with Steve Lillywhite at the helm. Their signature sound was relatively distinct from their post-punk contemporaries, but shared many characteristics with bands also produced or mixed by Lillywhite like early XTC and the classic “Siouxsie and the Banshees” lineup featuring guitarist John McGeoch and drummer Budgie (an important influence on U2’s early sound). Like many post-punk bands, U2 avoided the typical “power chord” approach that dominated most punk and hard rock from the late 1960s onward. U2 guitarist Dave Evans (The Edge) played angular, metronomic and atmospheric delayed arpeggios. His style has become synonymous with the use of dotted delay repeats to transform a rather simple picked eighth note arpeggio pattern or strum into unique, hypnotic and soaring sixteenth note “helicoptor-esque” patterns, later incorporating reverbs and harmonizers, but importantly, rarely modulation effects such as the Roland Boss chorus that was employed on nearly every clean guitar throughout the 1980s. His sound was all his own.

Essentially a power trio with a vocalist, every member of U2 had a comfortable frequency range and sonic territory to work within: Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen typically driving the root of the chord progression with a 4/4 beat while Edge played overdriven, shimmering melodic arpeggios in the higher frequencies that were sometimes vaguely reminiscent of Anglo-Celtic folk. U2‘s sound was immediately identifiable and original. Having been a band since their teenage years, they rarely if ever played or collaborated with any other musicians, and arguably couldn’t do anything but sound like U2. Vocalist Paul Hewson (Bono) in his younger years was a tenor with tremendous power, punching well above his natural range and with an often underappreciated genius for melody. The instrumental sound of U2 was atypical and helped offset Bono’s penchant for insanely catchy vocal lines that might have sounded schmaltzy in a more traditional 80s pop context.

1984‘s “The Unforgettable Fire” was a significant and risky left turn for the band, incorporating elements of ambient music and art rock at a time when their growing and loyal fan base was hungry for a follow up to the straight ahead militant pacifism of “War” and thanks to the reception of its live LP and video companion, “Live: Under A Blood Red Sky” recorded at Red Rocks Amphitheater in Colorado. Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois entered as the production team and pushed the band to innovate, refine their unique sound and largely abandon the post-punk formula they had used for the previous three albums.

Now, all this prologue culminates in the process of making a U2 record in 1986. Which, according to the many interviews I’ve watched and read over the years, was a tremendous and time consuming labor involving highly obsessive and sometimes insecure personalities that worked, reworked, deconstructed, reconstructed, re-arranged songs to death for weeks or months. The average age of the band members was 26.

Starting with “The Unforgettable Fire” album, at the suggestion of producer Danny Lanois, the band opted to record in non-studio spaces, avoiding the costs, time constraints and pressures of a formal hired professional facility. The band would continue to use variations of this approach for the rest of their career. The band rented the Georgian mansion, Danesmoate in Rathfarnham, Ireland, in the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains. Lanois encouraged the band to rehearse, learn their parts and cut the instrumentation live. To what extent live takes were actually achieved and made the final cut is unknown. Only “Trip Through Your Wires” and “Running To Stand Still” have a conspicuously live soundstage. The band and Lanois told new engineer Mark “Flood” Ellis that they wanted a sound that was “very open… ambient… with a real sense of space of the environment you were in,” which he thought was a very unusual request at that time. Like other classic albums such as The Rolling Stone’s “Exile On Main Street” or Led Zeppelin’s albums from “III” onward, the “on location” approach meant imperfect and unusual acoustic conditions, audio bleed and often forced any live performances by the band to take on the ambient characteristics of the space in which they were captured, making overdubs and the typical fixes afforded by a highly controlled acoustics of a pro studio environment difficult. If the guitars or vocals are bleeding into the drum mics, you can’t easily go back and change them. This approach and ethos contributed significantly to a soundstage and sonic signature that, along with the typically unorthodox guidance and sensibilities of Eno & Lanois, resulted in an album that sounded “out of time and place” in the context of 1987.

To very broadly paraphrase Brian Eno’s comments about the team going into the recording process, they looked around and saw a lot of artists trying exceptionally hard to be cool. There was an unusually high level of artifice or image over substance in pop music. U2 was never particularly good at that until Bono approached it as theatre on Achtung Baby with the larger than life on-stage alter-egos, “The Fly” and “Mr. Mephisto”. Bono and The Edge were open and unusually outspoken about their deep Christian faith, and they long had a reputation for being overbearingly earnest, preachy and self-righteous. Being inspired by the imagery, culture and contradictions of a largely protestant Christian America while touring the US, they wanted to make an album that was the opposite of the pop culture trends at the time; something modern yet spiritual, earthy, country, and rootsy, in contrast to the overblown, over-stylized and synthetic chic of the day, but without veering into the well-trodden and passe territory of 70s folk rock. Arguably, the result was the most successful & innovative “Americana adjacent” modern rock album until Wilco’s sleeper classic, “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot” in 2001.

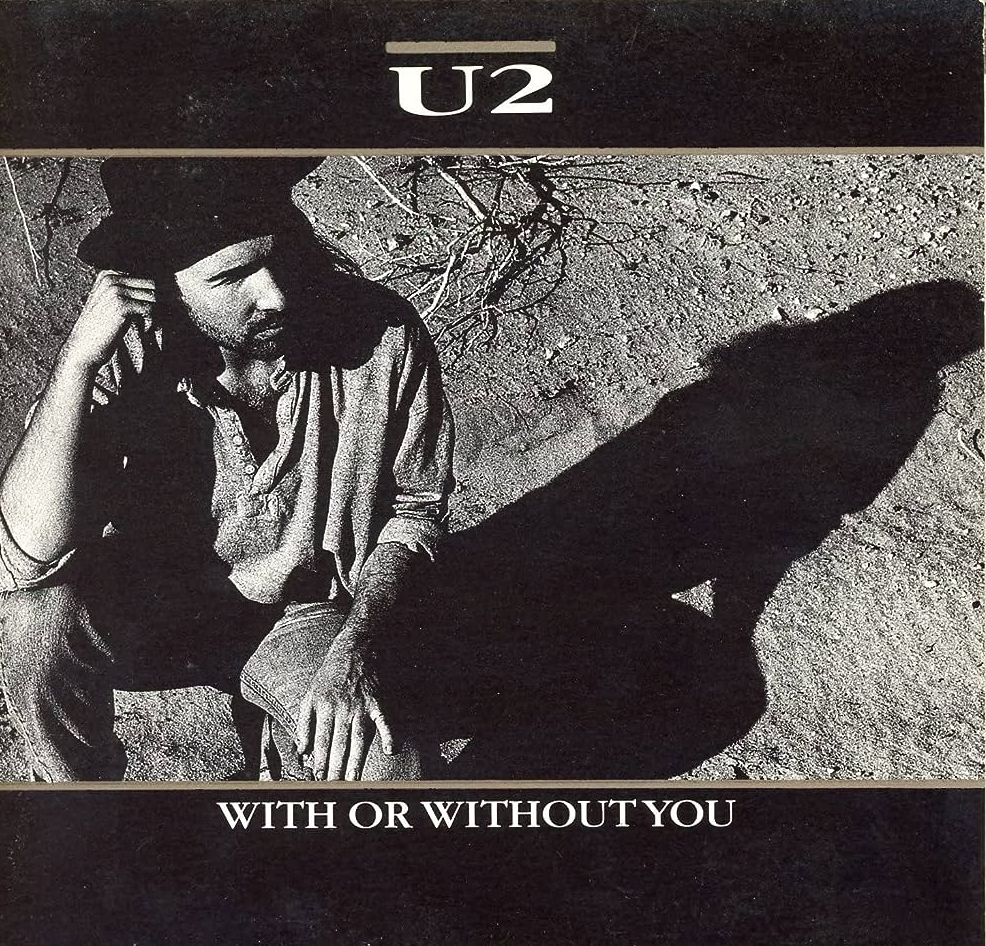

Everything about the marketing and presentation of “The Joshua Tree” centered on the theme of austerity, earthiness, and grit: from the striking high contrast black and white photography of the band in the deserts of Joshua Tree national forest by Anton Corbijn, to the band’s stylistic makeover with worn and tattered second hand clothing. The Edge in particular looked like he was straight out of central casting for an 1880s goldrush miner, or a Great Depression era dust bowl farmer. It was a well-crafted and convincing anti-image that helped further transform their public personas of bright-eyed idealistic post punk / new wave Irish youths into that of serious worldly men who knew a hard day’s work and got their hands dirty. This was an album that would expand their appeal to the idealistic boomer adults now in their 30s who “cared” but obviously didn’t identify with the struggles of hunger, intense austerity or homesteading in a desert, but had perhaps felt let down by the utopian promises of the countercultural revolutions of the 60s and 70s and were dealing with the realities of Reaganomics, kids, inflation, high interest rates and a highly competitive job market. In the mid 80s, everything in graphic design was neon, bright colors and triangular shaped salon haircuts, and there was an uneasy shallowness about it. The Joshua Tree packaging and photography stood out as the opposite: monochromatic, worn, unkempt and incidental. It was an artifact that attracted someone interested in the underlying seriousness of global inequality and was possibly concerned about a culture that was increasingly celebrating pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth.

The first single, “With Or Without You” was released on March 16, 1987 and by May it dominated the Billboard Hot 100 and the chart rankings of most of the English speaking world. With a nearly five minute runtime, it stood out like a sore thumb on top 40 radio, a remarkably sparse, brooding, ethereal number built around an otherwise simple I-V-vi-IV progression carried only by Adam Clayton’s bass line. I clearly remember hearing it on an FM stereo broadcast in our family car on a beautiful spring day. The high levels of compression and limiting on radio broadcasts brought forward all the little details in the intro: Brian Eno’s gentle, cascading DX-7 arpeggio loop with a subdued 4/4 rock drum machine pattern, the otherworldly and ethereal sound of The Edge’s “infinite sustain guitar” line teasing the listener. Then the bass line and full infinite guitar enters like a majestic, ethereal wedding march in a surrealistic black and white western film. Bono begins singing in his lowest register he’d recorded to date, sounding like an altogether different character. Older. Wiser. Having benefited from vocal coaching, it was the first performance on record that demonstrated his remarkable capability as a crooner with tremendous range. The song simmers, builds and then the sound of Larry Mullen’s signature marching tom and snare patterns played in a large natural space along with Edge’s signature angular delayed guitar. At that moment, the average listener knew it was U2. The song hits its peak crescendo with a tambourine and Bono belting a passionate wordless chorus and then cools down to a reflective falsetto, followed by a reserved and almost “twangy” guitar theme that repeats and builds over a synth reinforced bass to the ending fade. It’s a masterpiece of audio production.

Lyrically, despite Bono claiming it was about his struggles reconciling his roles as a rock star and a loyal husband and father, the imagery of nails, waiting, etc led many to believe that Bono was simply obscuring a more overt messianic message in the language of romantic love, which he continued to do throughout his career — simply replace “love” for “God” and “she” and “her” for “Him” and you have the Bono Rosetta Stone. Whatever the case, the lyrics were compelling, sexy, mysterious and effective enough for the average listener.

The initial versions of the song had largely been dismissed by the producers and most of the band as the mood didn’t work and they struggled to find an arrangement. It’s easy to imagine why that would have been the case. A direct rendition of the I-V-vi-IV progression with a standard strumming or “edge delayed” guitar part from the intro would be incredibly repetitive and predictable. According to the band, refusing to abandon the song after the producers dismissed it, Bono and his close friend Gavin Friday were in the control room listening to the song and working on ideas for an arrangement. In the adjacent live room, the Edge had just received the prototype of the infinite guitar, plugged it in and started experimenting with single note lines in the same key, completely oblivious to the song being played back in the control room. Hearing the haunting, almost pedal steel effect of the guitar over the track, Bono and Gavin urged Edge to come in and listen to the two together. They proceeded to reduce the mix to only the essentials, muting all the previous guitar parts, leaving only the bass line. In two takes, the Edge recorded one of the most powerful and memorable guitar performances of his career. The tension created by the minimal arrangement and haunting legato guitar lines was stunning.

In May of 1987, hearing that song for the first time in the car, I would have been twelve years old. I clearly remember it, including the street we were driving on (and yes, it had a name). It’s not that five minutes of music was extraordinarily revolutionary or unprecedented, but it was the first time I realized that I was deeply curious about exactly how they produced that sound. Many moody hits from bands like The Police, Talk Talk, Mr. Mister, Til’ Tuesday charted in the 80s, and many American artists like John Mellencamp and Tom Petty were doing “American Roots Rock”. But nothing had veered so far from the dominant production tropes of the day and climbed to number one. I had certainly never heard anything like it on the radio before. It sounded simultaneously cinematic, mystical, country and futuristic.

Nothing anchors “With Or Without You” or “The Joshua Tree” album sonically to 1987 except for the odd appearance of a few dated DX7 synthesizer pads, likely added by Brian Eno, most notably on “Red Hill Mining Town”. “With Or Without You,” could have been released in 1997, 2007 or 2017. The choices of effects were different: the ambient soundstage was organic, the drums lacked the ubiquitous 80s gated snare. The use of synthesized sounds were minimal, tasteful and supportive. The featured melodic instrument was a prototype “infinite guitar” built by Canadian guitarist Michael Brook that was capable of sustaining the notes of a clean electric guitar in new ways. Looking back at the Billboard Hot 100 that week, nothing else was in the sonic ballpark, barring Crowded House’s “Don’t Dream It’s Over.” “With Or Without You” is a timeless song. Here was an Irish post-punk band inspired by charismatic Christian spirituality, Cormac McCarthy novels, Sam Shepherd plays, Wim Wender’s 1984 film, “Paris, Texas”, Terrence Malick films, (“Badlands” and “Days Of Heaven”) and “big sky” America, translating Americana and a sense of wonder about the “idea and promise of America” back to Americans through the eyes of outsiders. Unlike peoples with deep historical cultural and national identities, America is a land of immigrants who are always struggling to define and redefine a narrative of what it means to be American. U2 provided one. It was an organic, moody, euphoric and authentic narrative during a time when everything was consumerism, hairspray, gated snares and shoulder pads.

The big 80s production sound would continue into the early 90s but I believe The Joshua Tree was a sonic turning point where trends began to veer back to a less glossy, more honest approach that would reach critical mass in the 90s and beyond. U2 came along and had a massive hit record that was both innovative and sounded like a live band — a band that was like no other on earth, and would go on to become one of the most successful stage and studio acts of the next 36 years and counting. The Joshua Tree tour grossed over 56 million in revenue.

In hindsight, “With Or Without You” is an unquestionable classic, but in terms of innovation and pushing the envelope of the rock production aesthetic, their subsequent work on “Achtung Baby”, or even their often overlooked cover of “Night & Day” in 1990 that pointed to a radical new direction for the band was far more sonically adventurous (or arguably trendy), incorporating elements of the emerging underground electronic and alternative music scene into the mainstream than the relatively safe and populist Americana leanings of “The Joshua Tree.” But context is everything. It’s one thing to make a highly experimental and innovative work in obscurity, and another to weave innovative sonic colors gradually into a palatable series of products that simultaneously achieve massive worldwide popularity and change the public’s taste. And durability matters. One hundred years from now, the public likely won’t be aware of “Mysterious Ways,” but there’s a good chance they will hear, “With Or Without You.” Having had extremely limited exposure to the vast catalog of what would would be called alternative music at the time, the success of that album offered a twelve year old kid in east Tennessee a valuable entry point into a world he’d explore for the rest of his life.