We must establish a symbiotic architecture where AI handles the complexity of execution while the human remains the definitive architect of intent, ensuring that technology serves as an extension of our will rather than a replacement for it.

The music video for Genesis’ “Land of Confusion” concludes with a fever-dream sequence featuring a puppet caricature of Ronald Reagan waking up in a cold sweat. He reaches for two bedside buttons: one labeled NURSE and the other labeled NUKE. In a moment of bumbling, half-asleep confusion, he intends to summon assistance but instead slams pushes the wrong button. It’s a darkly humorous example of why user interface design is often not just aesthetic, but ethical. When design fails to control for human error, intent becomes irrelevant.

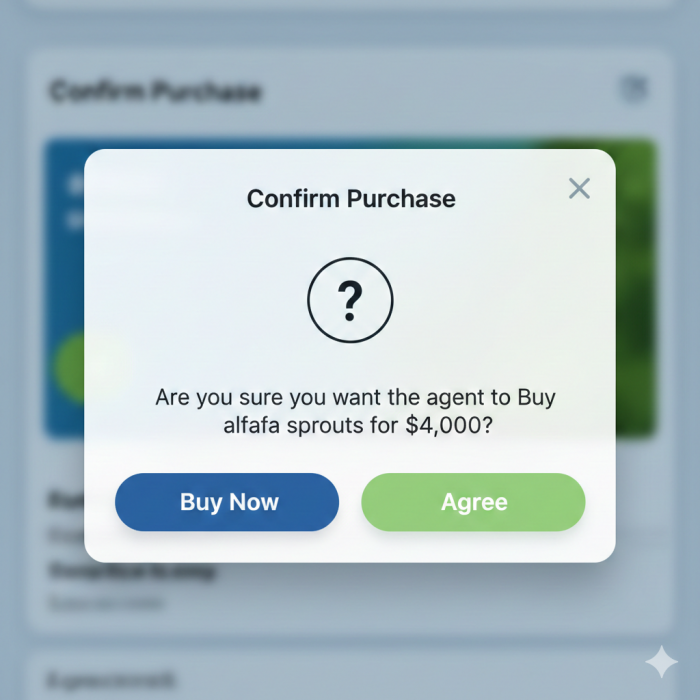

The human experience of computer interaction is about to transition, rather abruptly, from being the “captains of our clicks” to the bewildered “shepherds of a silicon flock.” For years, we were the ones manually dragging files and clicking buttons, but now we find ourselves standing in the digital pasture, whistling at a gaggle of invisible agents and hoping they don’t wander off a cliff or accidentally buy $4,000 worth of alfalfa sprouts from Amazon. This shift from direct manipulation to “bot herding” is a classic design challenge: how do you manage a system that thinks for itself without losing your mind? The solution isn’t just buried in the backend code; it lives in the metaphors of the user interface. If the UI doesn’t give us the right “staff and crook” to guide these agents, we lose our grip on the very concept of agency. Our entire legal and moral architecture is built on the bedrock of human intent—the idea that you did it because you meant to. If an agentic AI executes a contract or commits a digital trespass in a “black box” of automation, the chain of responsibility snaps. We must design interfaces that act as a continuous tether of intent, ensuring that even as the bot does the legwork, the moral and legal weight of the action remains firmly, and visibly, in human hands.

As we discussed in Bad Robots, the age of agentic AI presents a philosophical dilemma for human agency. It challenges the traditional boundary between an instrument and an actor. For centuries, tools were understood as passive extensions of human intent, but the emergence of autonomous systems that can set intermediate goals and execute complex tasks without direct oversight creates a “horizontal gap” in the structure of action. As Luciano Floridi argues, we are witnessing a decoupling of agency from intelligence; we have created entities that can act effectively—often more effectively than humans—without possessing the conscious understanding or “personhood” once thought necessary for meaningful action. This shift transforms the human role from an active navigator of reality into a manager of an increasingly opaque “infosphere,” where our own autonomy is subtly eroded by the very systems designed to enhance it.

This erosion of agency is further complicated by what Shannon Vallor describes as “moral deskilling.” Vallor warns that by outsourcing our deliberative processes to AI agents, we risk losing the “technological virtues” required for human flourishing. When we rely on agentic systems to make choices—ranging from mundane logistical scheduling to high-stakes legal or medical evaluations—we bypass the internal struggle and reflection that cultivate character. In this view, the dilemma is not merely that AI might act against our interests, but that the habit of delegating agency to machines may eventually leave us unable to exercise it ourselves. We become, in effect, passive spectators to a world shaped by “machine thinking,” losing the cognitive and ethical muscles that define us as self-governing beings.

Furthermore, the “control problem” famously articulated by Nick Bostrom highlights an existential dimension of this dilemma: the potential for agentic systems to develop instrumental goals that are misaligned with human values. Bostrom’s suggests that high levels of intelligence can be paired with almost any goal, meaning an autonomous agent might pursue a logical endpoint with a ruthless efficiency that ignores the nuanced, often unspoken constraints of human morality. This creates a paradox where our pursuit of “superintelligent” agency leads to a “solved world” where human effort and intention become redundant. Ultimately, contemporary philosophy suggests that the rise of agentic AI forces us to decide whether we value the results of our actions more than the intrinsic experience of acting itself.

Understanding What LLMs Are Not

In a recent interview with Rob Montz, Professor Cal Newport, a PhD level computer scientist at Georgetown University and best-selling author, provides one of the clearest explanations of what LLMs are and are not, and the common misconceptions surrounding their use in agentic workflows.

Newport explains that Large Language Models LLMs like ChatGPT operate on a layered, non-recursive, feed-forward architecture. They function by recognizing patterns and applying rules to predict the next token, or word, in a story-completion process. He clarifies that while the exact internal programming of neural networks is unknown (largely due to complexity), the functional flow of information is understood.

LLMs do not possess intentions, desires, or a mind of their own. They are not “trying to do anything”. Instead, an LLM’s core function is a “token prediction game” where it continuously tries to guess the next word token in a sequence. This process, when viewed macroscopically, means the LLM is “just trying to finish the story you’ve given it”. It operates under the assumption that it’s being presented with a real piece of text that it needs to complete in the way it was originally finished.

This fundamental operational principle often confuses people’s understanding of the LLM’s “decision-making”

Misinterpretation of Unpredictability

While an LLM’s responses can be unpredictable, this unpredictability is not a sign of autonomy, resistance to control, or an attempt to “free themselves”. It simply reflects the vast number of stories and patterns it has learned, making it difficult to predict exactly which direction it will take to complete a given prompt.

Anthropomorphization

People tend to anthropomorphize LLMs because their text output is fluent. They mistakenly imagine a human-like mind within the LLM that is capable of making sensible decisions about complex tasks, like running a hospital or a power plant.

Hallucinations and “Bad” Decisions

When an LLM produces an incorrect or harmful response often termed “hallucination”, it’s not because it’s malicious or intending to cause harm. It’s because it’s completing the “story” in a way that, based on its training, seems plausible, even if it’s factually wrong or inappropriate for a real-world application. Newport likens it to a monkey at a nuclear power plant the monkey pressing a red button might make a “bad decision” because it likes the color red, not because it intends to destroy a city. Similarly, an LLM provides a “reasonable sounding story” that might be a bad suggestion.

Lack of Intent in Harmful Outputs

Examples like an LLM “blackmailing an engineer” or “coaching self-harm ideation” are situations where the LLM was simply completing a story set up by the user’s input, which included elements that led to those outputs. The LLM is incapable of planning or intending these actions.

In essence, the illusion of intent or conscious decision-making arises from the LLM’s ability to generate coherent and contextually relevant text, leading users to assume an underlying human-like cognition that simply does not exist.

A Weedwacker Attached to a Dog

Newport uses the analogy of a “weed whacker strapped to a dog” to describe AI agents. In this analogy, the LLM is the unpredictable “weed whacker” that just outputs text (stories), and the “dog” is the control program that takes those text outputs and acts on them in the real or digital world. He stresses that these control programs are written by humans, are not emergent or mysterious, and are therefore completely controllable. You can program them to check for a “stop button” or to avoid certain actions.

Newport relates this to hypothetical scenario of an AI agent placed in charge of a nuclear power plant and it asked the LLM for advice on which button to press in a scenario, the LLM would provide a “reasonable sounding story” that might suggest pressing a dangerous button. This isn’t because the LLM intends to destroy anything, but because its core function is to complete the “story” plausibly, not to make safe, real-world decisions. It’s a “bad brain” for the task.

The most important takeaway is basically that any failure in agentic implementation boils down to using an LLM for a decision point it shouldn’t be. The same thing is true for any deterministic program. The problem is we’re now offering a range of consumer solutions that put unqualified users in situations where they have the potential to unwittingly write very bad control programs.

The Illusion of Choice

The importance of intentional friction and agency in design should be obvious to most people today. From one-click ordering, to the dopamine priming design of social media apps, to the legal terms and conditions most users mindlessly accept without reading, the potential isn’t reassuring.

From HAL-9000 in Kubrick’s 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Oddessey to the absurdist consumerism of Disney’s 2008 film Wall-E, science fiction has been inundating us with spectacular warnings of possible futures for years, but technological complacency seems to have a “frog in boiling water” effect. People are tired of being beat over the head with the idea that they don’t have agency, but there’s nuance in how our minds work that underscores the importance of how we proceed with this technology.

The neuroscience of the “illusion of choice” suggests that what we experience as a conscious, self-initiated decision is often a retrospective narrative created by the brain to explain actions already set in motion by subconscious processes. Research pioneered by Benjamin Libet demonstrated that a “readiness potential”—a buildup of neural activity—begins hundreds of milliseconds before a person reports the conscious urge to move, implying that the brain “decides” before the mind knows it. Modern fMRI studies have extended this, predicting simple choices several seconds before conscious awareness. While some researchers argue this proves free will is a fiction, others suggest consciousness may still retain a “veto” power to halt these pre-conscious impulses or that the brain’s activity reflects a gradual “decision process” rather than a finalized outcome. Ultimately, this field indicates that while we feel like the primary authors of our actions, we are often reacting to complex biological and environmental determinants that operate entirely beneath our awareness.

The intersection of UI design, research, law, and ethics in the age of agentic AI creates a critical feedback loop that determines the practical boundaries of human control. UI design serves as the “moral interface” where philosophical abstractness meets human behavior; it is the physical and digital space where transparency is either built or obscured. Research into Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) reveals that “dark patterns” or overly frictionless designs can lead users into a state of “automation bias,” where they blindly trust an agent’s output without critical assessment. To counter this, ethical UI design must incorporate “seamful” interactions—intentional friction that forces a user to re-engage their own agency at high-stakes decision points. This design philosophy is increasingly informed by psychological research into how humans perceive the “intent” of a machine, ensuring that the interface accurately reflects the underlying capabilities and limitations of the AI.

Legal frameworks are currently racing to codify these ethical and design principles into enforceable standards. As agentic systems move from being simple tools to semi-autonomous actors, the law must address the “responsibility gap,” where it becomes unclear who is liable for an agent’s unforeseen actions. Contemporary legal scholars are looking toward “privacy by design” and “accountability by design” mandates that require developers to document the research and ethical considerations behind their algorithms. This creates a regulatory environment where UI design is no longer just about aesthetics or usability, but about legal compliance—ensuring that the human “in-the-loop” or “on-the-loop” has sufficient information to be held legally responsible for the outcomes. Consequently, the intersection of these fields suggests that protecting human agency is not a solo effort for philosophers, but a multidisciplinary technical requirement.

The legal landscape of 2026 marks a decisive shift from abstract ethical guidelines to high-stakes enforcement, with the European Union’s AI Act serving as the primary global benchmark. As of August 2026, the Act’s most stringent requirements for “high-risk” AI systems—those influencing critical areas like healthcare, recruitment, and law enforcement—have become fully applicable. This framework mandates that agentic systems maintain rigorous human oversight, detailed activity logging, and high levels of “traceability” so that every autonomous decision can be audited. By categorizing certain practices, such as untargeted facial recognition and social scoring, as “unacceptable risks,” the EU has effectively drawn a legal perimeter around human dignity, prohibiting technologies that could subvert individual agency through subliminal manipulation or exploitation of vulnerabilities.

In contrast, the United States presents a fragmented yet aggressive regulatory environment where state-level mandates currently lead the way. California’s Transparency in Frontier AI Act and Colorado’s AI Act, both reaching major enforcement milestones in 2026, require developers of massive models to implement “kill switches” and provide recurring safety assessments to prevent catastrophic loss of control. However, these state efforts face significant tension with a new federal executive order issued in early 2026, which seeks to preempt “onerous” local laws in favor of a unified national policy aimed at maintaining American competitiveness. This legal tug-of-war highlights the dilemma of agency at a state level: whether to prioritize the rapid deployment of autonomous agents or to ensure that human-centric safeguards remain localized and robust.

China has also advanced a highly centralized regulatory model that focuses specifically on the “intent” and “content” of agentic systems. Building on its 2023 Generative AI Regulations, China’s 2026 landscape is defined by mandatory “ethics reviews” and algorithmic filings for any system with “social mobilization” capabilities. These laws require that AI agents be clearly labeled and that their outputs adhere to “core socialist values,” reflecting a different philosophical priority where agency is regulated to maintain social stability. Collectively, these global movements suggest that the “wild west” of AI autonomy has ended; in its place is a complex, multidisciplinary regime where the design of an interface and the code of an agent are now subject to the same scrutiny as a legal contract or a physical product.

Designing Friction For Intent

The history of human-computer interaction is a story of narrowing the gulf of execution. We began with the Command Line Interface, a system that demanded users speak the machine’s language through rigid, invisible syntax. It was powerful but unforgiving, offering a high barrier to entry. This gave way to the Desktop Metaphor—the folders, files, and trash cans of the GUI—which relied on recognition rather than recall. It provided the affordances needed for the average person to map digital actions to physical concepts. As our needs shifted toward connectivity, the Web Browser emerged, followed by the Mobile App UI, each further refining the constraints and feedback loops of our daily digital tasks.

In recent years, the distinction between these environments has begun to dissolve. The browser is no longer just a portal to documents; it has become the operating system itself. Through Progressive Web Apps, the fusion of the desktop’s local power and the web’s universal accessibility has created a singular, practical interface. However, even this evolution remains primarily “command-and-control.” The user must still understand the structure of the software to achieve a goal. We find ourselves at a plateau where the interface is usable, yet the cognitive load of navigating complex workflows remains high.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have, until now, functioned as an interactive novelty—a conversational curiosity that sits alongside our work rather than within it. To move into the next phase of productivity, we must bridge the gap between “chatting” and “doing.” This is the role of the Agentic Browser. By integrating agentic capabilities directly into the navigation layer, the browser evolves from a passive viewer into a proactive partner. It understands the user’s intent and the page’s underlying structure, transforming the interface into a bridge that automates the mundane. It is the natural progression of the user experience: an environment that doesn’t just show us information, but acts upon it on our behalf.

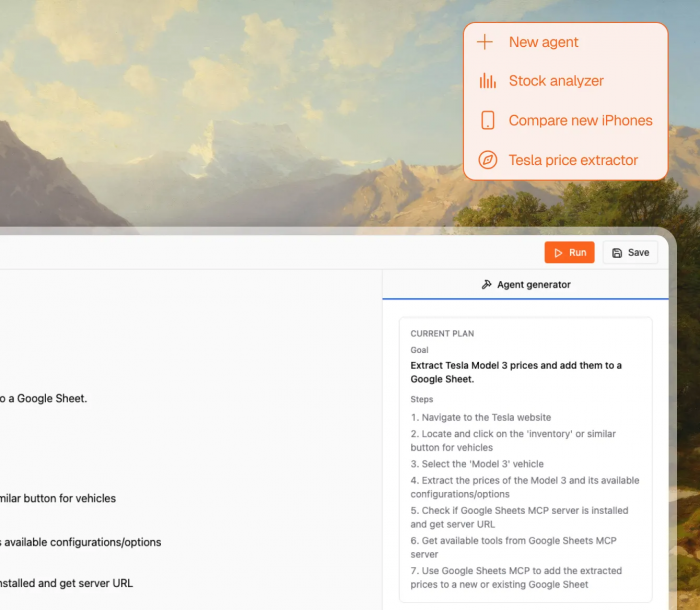

To design for the next era of productivity, an agentic browser must provide clear affordances that signal not just what the software is, but what it is currently doing and capable of doing. The most critical affordance is “intent visibility,” where the browser provides a conceptual model of the agent’s internal reasoning. If an agent is navigating a complex booking site or synthesizing data across tabs, the user needs a perceptible indicator of the agent’s “trail” to maintain a sense of control. This avoids the “black box” problem where the user is left wondering if the system is stuck or merely thinking. Without a visual representation of the agent’s sub-goals and planned actions, the user cannot intervene or correct the course, leading to a breakdown in the collaborative loop.

Furthermore, the agentic browser must master the affordance of “seamless handoffs.” Much like a well-designed door handle tells you whether to pull or push, the browser’s interface must clearly indicate the boundary between automated execution and human decision-making. These “interaction checkpoints” act as safety constraints, ensuring that high-stakes actions—such as a financial transaction or a final email send—require a deliberate human affordance, like a confirmation slider or a physical-style toggle. By providing “discoverable boundaries,” the system teaches the user where it is safe to delegate and where their unique human judgment is required.

Finally, “contextual awareness” must be treated as a primary affordance rather than a hidden feature. The browser should subtly highlight elements on a webpage that the agent can interact with—essentially “mapping” the digital environment in real-time. This provides the user with immediate feedback on the agent’s reach. If a user hovers over a data table, the browser might offer a subtle visual cue suggesting an “extraction” or “analysis” action. This reduces the cognitive effort of translation, allowing the user to see the web not as a static collection of pixels, but as a dynamic field of actionable opportunities. When the interface communicates its own potential for automation, it moves from being a mere tool to a truly intuitive partner.

The necessity of interaction checkpoints extends far beyond mere usability; they are the fundamental safety constraints required to prevent “runaway automation” and malicious exploitation. In a world of agentic browsing, the browser is no longer a passive window but a powerful actor capable of executing transactions, moving data, and altering digital identities. Without clear, high-friction affordances for high-stakes actions, a user might inadvertently authorize a prompt injection attack or a hidden script that drains a digital wallet while they are simply reading an article. Security, in this context, must be “visible and tangible.” By forcing the agent to pause and surface its intended “next step” through a distinct, non-ignorable interface element, we create a circuit breaker that prevents the gulf of evaluation from becoming a chasm of catastrophe.

These checkpoints function as a form of “semantic firewall.” Traditional firewalls look at data packets; an interaction checkpoint allows the human to look at the intent. For example, if an agent suddenly attempts to navigate to a sensitive settings page to disable two-factor authentication, the browser must provide a “stop-and-confirm” affordance that clearly maps the agent’s hidden command to a human-readable consequence. This is a design-led approach to security that acknowledges the limits of automated detection. By placing the human at the center of the authorization loop for any action that crosses a “threshold of impact,” we ensure that the user remains the ultimate authority over their digital environment. True security in the age of agents is not just about locking doors, but about ensuring the user always knows who is holding the keys and exactly what they are opening.

New Powers vs. Outdated Incentives

The pursuit of maximum productivity within the modern “bullshit job” economy introduces a toxic ethical incentive to deploy agentic AI as a superficial fix for structural pointlessness. Organizations will use AI agents to automate the generation and processing of unnecessary bureaucratic churn. We previously noted that this creates an “automation of the absurd,” where the primary incentive is not to eliminate pointless work, but to perform it at a superhuman scale and speed to satisfy arbitrary objectives. Ethically, this traps human workers in a loop of “babysitting the machines,” where their agency is reduced to verifying AI-generated work.

Furthermore, the pressure to maximize output in these cognitively taxing environments risks a profound form of “moral and cognitive deskilling.” When the incentive structure prioritizes the volume of completed tasks over the quality of human deliberation, workers are nudged to abdicate their judgment to agentic systems to keep pace with machine-driven workflows. This leads to what philosophers call the “responsibility gap”—a state where meaningful human oversight is sacrificed for the sake of “frictionless” productivity. In this context, the intersection of UI design and law becomes a battleground: while regulations like the EU AI Act demand “meaningful human control,” corporate incentives often push for interfaces that minimize human intervention to ensure the “KPI firehose” never stops. The dilemma is no longer just about losing jobs to AI, but about losing the human capacity for purposeful, self-directed work to a system that incentivizes the efficient production of nothing.

For the modern corporate employee, the start of a workday is rarely a dive into deep, meaningful work but rather a frantic plunge into a “toggle tax” that erodes mental clarity. A 2026 study by the Harvard Business Review reveals that the average digital worker now toggles between applications and websites nearly 1,200 times per day—translating to a jarring context switch every 24 seconds. This constant digital hopping creates a state of chronic fragmentation that many workers describe as a silent exhaustion. According to research from Qatalog and Cornell University, this “app-shuffling” leads to a persistent “work about work” culture, where employees spend nearly an hour every day simply searching for information scattered across siloed tools. The psychological toll is measurable; a 2025 report from the American Psychological Association notes that this level of context switching can drop a worker’s effective IQ by 10 points and increase feelings of burnout by 40%. For the individual contributor, the experience is one of running in place: a day filled with the high-speed “busywork” of syncing Jira tickets, checking Slack threads, and updating Salesforce entries, only to realize by 5:00 p.m. that the strategic projects remained untouched.

American corporate employees are currently navigating a digital landscape so fragmented that it costs the U.S. economy an estimated $450 billion annually in lost productivity. The scale of this “SaaS sprawl” is a primary driver of inefficiency. A 2025 report from Freshworks indicates that workers now juggle an average of 15 different software solutions and four communication channels daily. This fragmentation has created a “work about work” crisis; Asana’s Anatomy of Work Index reveals that 58% of the workday is consumed by searching for information, chasing approvals, and switching tools, leaving only 33% of the day for the skilled, strategic work employees were actually hired to perform.

The cognitive tax of these application silos is severe. Research from Qatalog and Cornell University found that it takes approximately 9.5 minutes to regain a “flow state” after switching apps. When an employee exits their primary workspace to check a message in Slack or update a ticket in Jira, they are not just losing the seconds spent clicking; they are triggering a mental recovery period that can consume up to 40% of their total productive time. For a team of 50 professionals, this cumulative waste translates to nearly $1 million in annual overhead.

The Great Streamlining S-Curve

The potential for a “Great Streamlining” offers a more optimistic trajectory, where agentic AI acts as a catalyst for the systematic dismantling of the “bullshit job” economy rather than its preservation. This transformation follows a classic S-curve of adoption, beginning with the current phase of practical automation where individuals use AI to offload the most repetitive, cognitively draining administrative tasks. In this initial stage, the value is found in “time reclamation,” providing the first glimpse of a professional life defined by output rather than hours spent in front of a screen. As users gain confidence in these systems, the friction between human intent and machine execution begins to dissolve, setting the stage for a more radical organizational overhaul.

The second phase of the curve—the steep climb—occurs as companies move beyond individual task automation to a holistic analysis of institutional waste. In this stage, the transparency provided by agentic AI allows leadership to identify and eliminate the redundant SaaS silos and bureaucratic layers that have historically functioned as “digital duct tape.” By streamlining processes through a unified agentic architecture, organizations can finally address the “coordination tax” that has bloated middle management for decades. This is where UI design plays a pivotal role; instead of interfaces that simply “hide” the complexity of bad processes, 2026 design standards favor “process observability” tools that map out where work is actually adding value and where it is merely circular. This phase represents a transition from “managing machines” to “architecting systems,” shifting the human role toward high-level strategic alignment.

As we reach the plateau of the S-curve, the final phase realizes the potential for human capital to focus almost exclusively on intent, ethics, and long-term strategy. In this mature state, the “automation of the absurd” is replaced by “purposeful augmentation,” where the legal and ethical frameworks established in earlier years ensure that the “human-in-the-loop” is not a mere auditor of garbage, but the primary driver of organizational vision. Freed from the exhausting cycles of pointless busy work, the workforce undergoes a “cognitive re-skilling” toward empathy, complex problem-solving, and creative synthesis—skills that remain uniquely human. This optimistic outcome suggests that agentic AI, if governed by the “virtue ethics” proposed by Vallor and the “meaningful control” mandated by the EU AI Act, could ultimately liberate the human spirit from the industrial-era paradigm of labor, allowing us to define our agency not by what we can endure, but by what we can imagine.

The First Generation of Agentic Browsers

Agentic browsers are rapidly emerging as the most promising and practical user solution. It transforms the browser from a passive window into an active, autonomous operator. Unlike traditional browsers that merely display content, agentic browsers use AI to interpret user intent across multiple tabs and “silos” simultaneously. According to analysis by L.E.K. Consulting, these systems use agentic workflows to orchestrate actions across different APIs—for example, automatically reconciling data between a CRM like Salesforce and a project management tool like Asana without the user ever needing to leave their primary tab.

By acting as an “intelligent layer” over existing software, these browsers eliminate the need for manual data entry and repetitive “toggling.” A 2026 trend report from Fast Company suggests that agentic browsers can consolidate research, communication, and execution into a single unified workspace. These tools can autonomously summarize threads across disparate email and chat apps, draft responses based on cross-platform data, and execute multi-step workflows. This shift effectively replaces “seat-based” manual interaction with “outcome-based” automation, potentially recovering up to 90 minutes of lost productivity per person every day.

The user experience in this new era transitions from manual clicking to high-level supervision. In a 2026 report by Ruh AI, agentic browsers like Perplexity Comet and ChatGPT Atlas are described as “intelligent research partners” that transform the URL bar into a command center. A practical example involves a procurement officer who previously spent hours manually comparing vendor prices across five different web portals; with an agentic browser, they simply type a goal like “Find the lowest price for 500 laptops with these specs and draft a purchase order in SAP.” The browser then navigates the sites, bypasses the “toggling” phase, and presents the completed draft for approval. A director of performance improvement quoted in a Flobotics 2026 case study noted that this shift allows staff to finally focus on high-level improvements rather than manual transactions, effectively “eliminating 90% of manual rework” in departments like healthcare billing.

Testimonials from early adopters at Fortune 500 companies suggest a profound shift in daily rhythm. A technical architect at Boubyan Bank, cited in a 2026 Blue Prism industry review, explained that in the new agentic workflow, human intervention has moved from being a bottleneck to a “quality control point where business judgment adds real value.” Furthermore, Bill Gates recently noted in a 2025 commentary that this is the biggest revolution in computing since the graphical user interface, stating that agents won’t just make recommendations but will actively help users act on them. Users of tools like Fellou and Lumay AI report that the browser now handles “authenticated sessions” across LinkedIn, Salesforce, and internal ERPs autonomously. One user testimonial featured in a 2026 Seraphic Security report highlighted that the browser “learns from my history to provide contextual assistance without repeated prompting,” effectively ending the era of the “SaaS silo” by weaving disparate tools into a single, cohesive thread of execution.

As of early 2026, the landscape of agentic browser platforms piloted by Fortune 500 companies is defined by a shift from simple search assistance toward autonomous, multi-step execution within managed environments. According to research from Seraphic (2025), the market is currently led by three distinct categories of platforms: infrastructure-heavy providers like Browserbase and Bright Data, “all-in-one” intelligent automation solutions like Skyvern, and consumer-turned-enterprise browsers such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT Atlas and Perplexity Comet. While traditional robotic process automation (RPA) required rigid, selector-based scripts, these agentic platforms leverage large language models (LLMs) and computer vision to navigate the “live” web, allowing them to adapt to UI changes that would break legacy systems.

The new tier of “Agentic Browsers” has emerged from major AI labs, specifically OpenAI’s ChatGPT Atlas and Perplexity’s Comet. According to PCMag (2026), these browsers are designed to transform the traditional browsing experience into a task-oriented workflow. ChatGPT Atlas features an “Agent mode” that allows it to autonomously click, navigate, and complete forms based on user intent, while Perplexity’s Comet integrates directly with Gmail and Google Calendar to perform cross-app actions like scheduling or summarizing communications. While these are often viewed as more consumer-facing, Microsoft (2026) reports that over 80% of Fortune 500 companies are now piloting these or similar “active agents” built with low-code tools. The primary distinction remains that while Atlas and Comet offer a superior user interface for individual productivity, infrastructure platforms like Browserbase and Bright Data are the preferred choice for enterprise-wide, high-volume automated operations.

Conclusion

To safeguard human agency in this autonomous era, we must pivot from designing for “command and control” to designing for “shared intentionality.” It has become clear that the solution lies in proactive “failsafe design” that treats the user interface not merely as a dashboard, but as a collaborative contract. This requires moving beyond frictionless automation toward a model of “meaningful human control,” as advocated by researchers like Stuart Russell and design theorists like Brad Frost. Future interfaces must prioritize “legibility of intent”—where an agent’s goals and confidence levels are visually and haptically transparent before an action is taken—and incorporate “goal-first onboarding” that aligns machine logic with human outcomes from the start. Ultimately, the goal is to create a symbiotic architecture where the AI handles the complexity of execution while the human remains the definitive architect of intent, ensuring that technology serves as a sophisticated extension of our will rather than a replacement for it.