To understand Decentralized Finance or DeFi, we have to consider that the core design of the Internet itself is based on a decentralized protocol, and it seeks to leverage the Internet’s vast global infrastructure to allow financial transactions in a decenralized manner. ARPANET was developed in the late 1960s by the United States Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) as a way to create a robust, fault-tolerant communication system that could survive disruptions, including potential attacks during the Cold War. The goal was to link computers at research institutions and universities to share information and computing resources more efficiently. Traditional communication systems relied on centralized hubs, which were vulnerable to single points of failure. To counter this, Arpanet was designed as a decentralized network using packet switching, a method that breaks data into small packets and routes them independently across the network. This architecture ensured that if one node or pathway was compromised, the data could still reach its destination through alternate routes. The decentralized nature of Arpanet laid the foundation for the modern internet, promoting resilience, scalability, and open collaboration among diverse institutions.

The development of blockchain technology was shaped by decades of foundational computer science concepts that gradually converged into a new paradigm for decentralized trust. In the mid-twentieth century, cryptography emerged as a critical field, enabling secure communication through techniques like public key encryption and hash functions. These tools laid the groundwork for digital signatures and tamper-proof data structures. Distributed computing evolved alongside, with researchers exploring how networks of computers could coordinate without central control. Concepts like Byzantine fault tolerance and consensus algorithms addressed the challenge of agreement in unreliable systems. The rise of peer-to-peer networks in the 1990s, exemplified by file-sharing platforms like Napster and BitTorrent, demonstrated how decentralized systems could scale and resist censorship. Meanwhile, digital cash experiments such as David Chaum’s DigiCash and later b-money and Hashcash explored how to create scarcity and value in digital form. These ideas culminated in the 2008 release of the Bitcoin white paper, which synthesized cryptographic security, distributed consensus, and economic incentives into a single system. Blockchain emerged not as a sudden invention but as the product of decades of research into how to build trust without intermediaries.

Core Technical Concepts

Distributed proof of work operates by requiring computers across a network to solve complex mathematical puzzles in order to validate transactions and add new blocks to a digital ledger. Imagine a massive lottery where thousands of participants race to find a winning number that meets specific criteria. Each participant, or computer, tries different combinations until one finds the correct answer.

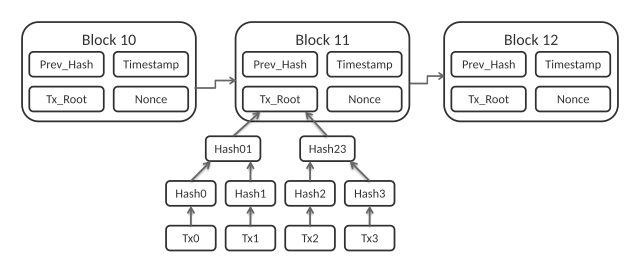

Hashing is like creating a digital fingerprint of information. When you hash something, you run it through a mathematical formula that produces a fixed-length string of characters. This string is unique to the original data, so even a small change in the input will produce a completely different hash. Hashing is commonly used to verify data integrity, such as checking passwords or ensuring files haven’t been tampered with. Importantly, hashing is one-way, meaning you can’t reverse it to get the original data.

Blockchain is like a digital notebook that is shared across many computers, where everyone can see and agree on what is written. Instead of one person keeping track of transactions, the whole network works together to record and verify each entry. Every time something new happens, like someone sending money, it gets added to a new page called a block. That block is then linked to the previous one, forming a chain. Once a block is added, it cannot be changed, which makes the system very secure and trustworthy. Because no single person controls the notebook, it is decentralized, meaning everyone has equal access and power to keep it running. Blockchain uses proof of work as a way to make sure that everyone agrees on the order and validity of transactions without needing a central authority.

A block in a blockchain cannot be changed after it is added because each block contains a unique hash, which is created based on its contents and the hash of the previous block. If someone tries to alter any information in a block, its hash changes, breaking the link to the next block and alerting the entire network. Since the blockchain is stored across many computers, all participants would immediately notice the inconsistency. To successfully change a block, a person would need to rewrite every subsequent block and convince the majority of the network to accept the altered version, which is practically impossible due to the immense computing power required. This design makes the blockchain secure and tamper-resistant, ensuring that once data is recorded, it remains permanent and trustworthy.

The DeFi Social Movement

DeFi is often hailed as a revolutionary response to the 2008 financial crisis. It’s been a kind of techno-anarchist uprising against the opaque, centralized institutions that nearly collapsed the global economy. The blockchain protocol and cryptocurrencies captured the imagination of millions, enjoys a fervent cult-like following, and continues to propagate and garner tremendous interest. From a first principles perspective, it has re-imagined and repackaged established traditional financial primitives that inspire speculation but it has not yet reached the critical mass or proven the technical viability necessary to completely displace existing systems at scale. Instead of banks, we have ledger protocols. Instead of regulators, we have smart contracts. And instead of trust, we have cryptographic consensus. All of these can hypothetically operate outside of a centralized authority, and displace a substantial portion of traditional financial institutions.

The cryptocurrency community is as much about a social movement as money. Its extremists are rebellious utopians, its moderates are optimistic futurists, its average users simply opportunistic. It has overlapped other distinct groups like tech-bros, anarcho-libertarians, conspiracy theorists and financial influencers. It promises liberation from banks, governments, and the indignities of fiat. It blends libertarian ideals, distrust of institutions, and a promise of financial liberation into a narrative that attracts many fervent advocates. The movement thrives on speculative hype, tribal loyalty, and symbolic gestures like memes and slogans, creating a culture that combines faith and financial innovation. Its communal language of hodling, mooning, diamond hands, paper hands, WAGMI, IYKYK and laser eyes are not just economic acts but symbolic gestures of in-group membership.

The novelty and technical complexity of DeFi is pregnant with speculative opportunity. The space is rife with techno-futurists who pitch new ideas that are replacements for long-standing standards in professional finance, and thus why the establishment did not take it seriously until it could be exploited for profit. The institutional adoption of all forms of DeFi thus far has been a mix of pragmatic greed and containment, not necessarily ideological conversion. Blackrock doesn’t necessarily care about Bitcoin, they just want 15-20 bips on their growing AUM. The rhetoric of democratization and decentralization is thick, but the reality is that most DeFi platforms are incomprehensible to the average person without a background in computer science and finance. It’s this complexity that has allowed evangelists to morph its narrative into whatever the target audience wants to see and hear.

DeFi has the potential to lower barriers to entry and subvert financial regulations. The idea that someone in an underserved region can now lend or invest through a blockchain is potentially a good thing that regulators who are obligated to follow international laws are obviously uncomfortable with. Tokenization of securities and contracts is pitched as a breakthrough, but it’s just fractional ownership, something mutual funds and REITs have done for decades. The difference is that those came with oversight. DeFi poses the opportunity to simultaneously transform traditional finance with new programmable “rails” and remove market safeguards, which will naturally be exploited.

As of 2025, Bitcoin’s market cap is approximately $2.4 trillion, representing less than 1.5 percent of all global investable risk assets, which are estimated to exceed $170 trillion.

Bitcoin remains a relatively small slice of the global financial system despite its outsized influence in media and investor sentiment. The total market capitalization of all cryptocurrencies is around $4 trillion, with Bitcoin accounting for roughly 60 percent of that value. In comparison, global investable risk assets which include equities, corporate bonds, real estate, and alternative investments. Combined these are estimated to be well over $170 trillion. This means Bitcoin’s share is still modest, though its growth trajectory has been steep.

Bitcoin’s market cap has surged due to institutional adoption, ETF inflows, and its positioning as digital gold. For example, U.S. spot Bitcoin ETFs have accumulated over 1.29 million BTC, or about 6 percent of the total supply. Despite this momentum, Bitcoin’s market cap remains dwarfed by traditional asset classes like U.S. equities, which alone exceed $50 trillion. The relatively small footprint of Bitcoin in global portfolios suggests significant room for expansion, but also highlights its current volatility and speculative nature compared to more established assets.

The cryptocurrency movement has been shaped by a diverse group of pioneers, innovators, and advocates whose ideas and actions have defined its evolution from fringe technology to global financial force.

The story begins with Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin, who published the foundational white paper in 2008. Nakamoto’s vision of a decentralized, peer-to-peer cash system solved the double-spending problem and introduced the concept of blockchain and proof of work. Though Nakamoto disappeared from public view in 2010, their influence remains central to the ethos of crypto.

Following Bitcoin’s launch, Hal Finney, a cryptographer and early Bitcoin recipient, helped test and promote the technology. His work in digital privacy and cryptographic systems laid important groundwork for the movement. As Bitcoin gained traction, Roger Ver, dubbed “Bitcoin Jesus,” became one of its most vocal evangelists, investing in early crypto startups and pushing for adoption.

In 2015, Vitalik Buterin revolutionized the space by launching Ethereum, a platform that expanded blockchain’s utility beyond currency. Ethereum introduced smart contracts, enabling decentralized applications and spawning entire ecosystems like DeFi and NFTs. Buterin’s technical vision and philosophical commitment to decentralization made him a leading figure in Web3 development. Gavin Wood, co-founder of Ethereum and creator of Polkadot, contributed key innovations in blockchain architecture and interoperability.

On the infrastructure side, Changpeng Zhao (CZ), founder of Binance, built one of the world’s largest crypto exchanges, shaping global trading and liquidity. Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase, brought crypto to mainstream investors by launching the first publicly traded crypto company in the U.S. His efforts to work with regulators positioned Coinbase as a bridge between traditional finance and digital assets.

Michael Saylor, executive chairman of MicroStrategy, emerged as a corporate champion of Bitcoin. Starting in 2020, he led his company to accumulate hundreds of thousands of BTC, framing Bitcoin as digital gold and a hedge against inflation. His bold strategy inspired other institutions to follow suit, making him a key voice in Bitcoin’s institutional adoption.

Other influential figures include Jack Dorsey, founder of Block Inc., who advocates for Bitcoin as a tool for financial empowerment, and Elizabeth Stark, CEO of Lightning Labs, who works to scale Bitcoin for everyday use through the Lightning Network. In the DeFi space, Andre Cronje developed platforms like Yearn Finance, enabling users to earn yield without traditional banks.

Michael Saylor is now the most influential figure in the cryptocurrency movement, championing Bitcoin as the ultimate store of value and a strategic asset for corporations. MicroStrategy has built the largest corporate Bitcoin treasury, holding over 629,000 BTC. Saylor advocates for Bitcoin-backed capital strategies, using debt and equity offerings to fund large-scale purchases. His influence stems not only from the scale of his investments but also from his outspoken belief that Bitcoin offers a solution to failing corporate treasuries and inflationary pressures. Through keynote speeches and public advocacy, he has positioned Bitcoin as a cornerstone of financial resilience in the digital age.

Because Strategy is a publicly traded company, anyone who owns the popular total market index funds like VTSAX, VTI or VT owns Bitcoin indirectly. As of October 2025, Strategy (MSTR) ranks approximately between 161st and 207th in market cap among U.S. publicly traded companies, depending on the source. MicroStrategy’s market capitalization has surged to around $99.78 billion, driven largely by its aggressive Bitcoin holdings and strategic positioning as a Bitcoin-backed capital vehicle. This dramatic rise from under $2 billion just a few years ago reflects investor enthusiasm for its Bitcoin-centric strategy, which has made it one of the most watched tech stocks in the cryptocurrency space.

Crytocurrency and DeFi have faced significant skepticism and criticism. Among its fiercest critics, Stephen Diehl argues that the crypto industry is built on “weaponized jargon”, sophistry and logical contradictions. He highlights the incoherence of competing narratives: that Bitcoin cannot be both a stable hedge and a volatile investment, nor can it serve as an everyday currency while being inefficient and hoarded like gold. DeFi claims to replace traditional finance yet relies on it for legitimacy, and NFTs promise democratization while enriching a small elite. Despite these inconsistencies, Diehl suggests they are overlooked because the underlying appeal of crypto is simple: the seductive promise of effortless wealth.

Diehl notes in his 2025 blog post that, “The average person, overwhelmed by technical terminology and afraid of appearing ignorant, becomes susceptible to whatever narrative most appeals to their hopes and fears. Meanwhile, true believers can choose whichever story best fits their ideological preferences, constructing elaborate post-hoc justifications while ignoring the glaring contradictions in their position.”

Viability of the Technology

Ideological debates aside, there is clearly a vibrant industry in the space and its growing impact on finance and economics cannot be ignored. The question is whether the underlying technologies can live up to the fervor and marketing hype, or will the technology inevitably be cast aside, a hollow shell of its ethos, living on in name only as its “brand power” is strategically co-opted by dominant interests.

Security

The history of DeFi hacks to date is a cautionary tale of rapid innovation outpacing security. In 2021 alone, over $3.2 billion in crypto assets were stolen, with 72% of that coming from DeFi protocols. The most common attack vectors include flash loan exploits, which manipulate internal exchange rates or governance mechanisms, and smart contract vulnerabilities, often stemming from unaudited or poorly written code. High-profile breaches include the Poly Network hack in 2021 ($610 million), the Wormhole bridge exploit in 2022 ($320 million), and the Ronin Bridge attack in 2022 ($625 million). These incidents highlight how DeFi’s open-source transparency also makes it a prime target for sophisticated cybercriminals. By 2024, the number of DeFi exploits had climbed to 303, with total losses exceeding $4.28 billion. Despite growing awareness and improved auditing practices, the pace of attacks continues to rise, underscoring the persistent fragility of decentralized financial infrastructure.

A 2025 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that approximately 36% of the total price decline following DeFi protocol hacks occurred before public announcements, indicating that sophisticated traders rapidly processed on-chain data to anticipate and front run market movements. This suggests DeFi’s transparency enables faster price discovery for those with the tools to interpret blockchain data. However, the same study emphasizes that information frictions—especially processing costs—limit how quickly prices reflect public data, meaning transparency alone doesn’t guarantee efficiency. Other research highlights DeFi’s potential to reduce costs and broaden access, but also warns of systemic risks and liquidity fragmentation that can undermine stability. In short, DeFi shows promise in improving price responsiveness, but its benefits are unevenly distributed and constrained by technological and cognitive barriers.

Blockchain’s Scalability Problem

From the perspective of computer science, technology is ethically neutral. All that matters is if it is the right technology for the application use case. The success or failure of these new blockchain and tokenization systems will depend on what value it can deliver the end customer, if it is reliable, if it is robust enough to handle the transaction load and if it can be done at a lower cost than current solutions that are remarkably durable and optimized. As a software engineer, the author is familiar with 25 years of technology fads that have come and gone, and a lot of it amounted to nothing more than preference trends that attracted a new generation of followers that didn’t add substantial value or robustness that couldn’t be otherwise explained by the declining costs of compute. Decentralization of compute and decentralized protocols are nothing new — they are the backbone of the Internet itself, the open source software movement and much of the technology you’re using right now reading this. And while incredibly powerful in terms of freedom, the complexity and problems associated with the reliability of distributed systems have a interesting way of reverting back to centralized architectures for practical reasons of compliance, security and reliability.

Variations of blockchain technology in finance are a solution, but not necessarily the right solution.

The blockchain trilemma is the long-standing challenge of achieving optimal levels of decentralization, security, and scalability simultaneously in a blockchain network. Developers can only maximize two of these three properties at any given time, forcing a fundamental trade-off.

- Decentralization: Refers to distributing power and control across a wide network of independent participants (nodes) rather than a single, central authority. It is key to a blockchain’s resistance to censorship and single points of failure, but it can slow down transaction processing.

- Security: Pertains to a blockchain’s resilience against malicious attacks and fraudulent activity. Security is often guaranteed through robust consensus mechanisms, but rigorous security protocols can sometimes limit scalability.

- Scalability: Measures the network’s ability to handle a high volume of transactions and users without becoming slow or expensive. This is crucial for mass adoption, as platforms like Visa can handle thousands of transactions per second, far exceeding the throughput of many traditional blockchains.

Software engineers noted early in Bitcoin’s adoption lifecycle that the design was obviously too slow to serve as everyday money because its network can only process about 7 transactions per second, with confirmation times ranging from 10 minutes to an hour, making it impractical for real-time payments. This inefficiency combined with mathematical scarcity arguably contributed to its gold-like properties in modern markets. Gold is expensive because it is a physical irreducible element that is relatively scarce and hard to move from point to point. The Bitcoin Lightning Network was a promising solution, but has been criticized for security risks like possible collusion among node operators, which could cause financial losses. It also falls short of its claims on decentralization and scalability, casting doubt on its effectiveness.

Real World Use Cases?

Supporting all global market trading transactions would require sustained throughput of at least 100,000–500,000 transactions per second (TPS), and while Solana, the leading technology for this use case has demonstrated an impressive peak performance above 100,000 TPS in stress tests, its real-world capacity remains far lower—typically around 3,000 TPS. To replace all market trading across equities, derivatives, forex, and crypto, Solana would need consistent, low-latency throughput across diverse transaction types, which current infrastructure cannot yet support. Upcoming upgrades like Firedancer and Alpenglow aim to improve scalability, but widespread adoption for global trading remains a future possibility, not a present reality.

In terms of consumer payment transactions, Solana’s real-world scalability remains limited compared to traditional payment networks like Visa and Mastercard, which consistently handle up to 65,000 transactions per second (TPS).

Solana has demonstrated peak performance in actual user-generated throughput typically averages around 400–3,600 TPS. This gap between theoretical and practical performance reflects challenges in executing complex smart contracts, maintaining validator reliability, and ensuring consistent network uptime. Unlike Visa and Mastercard, which offer stable, high-throughput infrastructure with decades of optimization, Solana’s blockchain must balance decentralization, security, and scalability. These limitations may hinder its adoption for mainstream payment processing, where reliability and speed are non-negotiable.

A latent effect of de-fi is a newfound appreciation of Visa and Mastercard’s tremendous value. Visa and Mastercard, with their global reach, near-instant settlement, and robust fraud protections, began to look less like outdated incumbents and more like indispensable infrastructure. In failing to replace traditional finance, blockchain inadvertently reinforced its value. Over the past decade, Visa and Mastercard have delivered strong performance, with both stocks more than tripling in value thanks to global expansion, digital payment growth, and consistent profitability.

It’s been interesting, in the tragicomic sense, watching the cryptocurrency space reinvent 19th century banking with all its chaos, speculation, and unregulated bravado, but without the top hats and mustaches. Aside from the novelty of applying block sequenced tokenization and cryptographic proof to financial systems to offer a decentralized datastore, the fundamentals of payment verification and settlement remain the same in terms of what consumers actually want: speed, reliability, security and low cost. Cryptographic timestamps, merkle trees, and proof-of-work predated the Satoshi Nakamoto whitepaper by at least 25 years and finance was one of the first sectors to adopt them. Blockchain is thus relatively valuable. Much of what we’ve seen thus far is not the birth of a radically new financial paradigm but a digital reenactment of the wildcat banking era, where private institutions issued their own notes backed by questionable reserves and collapsed with alarming regularity. Bitcoin becomes the new gold, stablecoins the new banknotes, and DeFi platforms the new trust companies, all operating in a regulatory vacuum that eerily mirrors the pre-Federal Reserve and SEC landscape. The irony is that these systems were abandoned precisely because they were so unstable and wrought with fraud and arbitrage, and yet here we are, celebrating their return as innovation that will eventually be regulated, fractionally reserved and indistinguishable from their institutional precursors.

Stablecoin & The L2 Hype-ocrisy

A stablecoin is a type of cryptocurrency designed to maintain a stable value by being pegged to a reserve asset, typically a fiat currency like the U.S. dollar. Unlike volatile cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, stablecoins aim to provide price consistency, making them useful for everyday transactions, remittances, and as a store of value. Stablecoin technologies like Solana show promise for handling future transaction volumes, but their current throughput limitations mean they are not yet fit to support their potential TAM.

When we look at the problem through the lens of software systems architecture, it’s simply a matter of fit for use case. To work around these performance limitations, providers utilize what’s termed “Layer 2” technologies. This sounds like what the marketing team named their hack to make the wrong technology fit the business use case. The raison d’etre of blockchain was to eliminate middlemen, yet L2s reintroduce them in the form of centralized sequencers, opaque governance structures, and trust assumptions that are identical to the very institutions crypto was meant to replace. It’s as if a group of anarchists built an off grid commune, realized plumbing and solar was hard, and quietly hired contractors to dig underground lines to the county water and electrical systems. Are purists pretending this is still a revolution when it’s a privatized toll road with a blockchain-themed gift shop?

Many of the “Layer 2” workaround solutions top providers are using are humorous in that they “bundle” transactions or bypass the blockchain altogether with traditional technologies and post the summary back to the chain. The justifications and rationalizations are surely extensive, probably referring to “integrity with the source of truth” a “decentralized network of private networks” or some other marketing speak to avoid cognitive dissonance. In fact, the cult of advocates probably spun this as an innovation.

As of early 2025, Layer 2 networks process hundreds of transactions per second, compared to Ethereum’s base layer capacity of just 15–30 TPS. 50% of Ethereum’s transactional volume is executed on L2, which is not at all surprising given that dismal throughput. This offloading is not marginal: over $42 billion in assets are “secured” on L2 chains, and millions of daily users rely on them for cheaper, faster transactions. The adoption of L2s like Optimism, Arbitrum, and zkSync has led to a 93% drop in Ethereum gas prices over the past year, indicating that a majority of transactional activity is now happening off-chain. The names are noteworthy. Optimistic artbitrage of sneaky sync?

One can be glad to see these companies innovate and succeed, but at what point is this just marketing hype around a crypto themed system that arguably could bypass the blockchain and just post a daily mark to market to the proof chain? If it’s all about the sacred blockchain, what’s the difference between 50 and 99.99999%?

As a nuts and bolts point of comparison, a single optimized open source workhorse Postgres relational database writer/replica pair on modern hardware benchmarks between 50k-100,000 TPS with practically flawless durability and transactional integrity (ACID compliance). Tibco kdb+ can achieve throughput of over 300 million inserts per second in optimized environments, making it a database of choice for time-series and financial data.

If we’re talking about securely storing transactional data, it’s not even close. Solana or new L1 technologies are promising, but are we taking anything but Solana seriously for even mid-range global TAM use cases for ETFs and specialty products? “We’re sorry, but your ETF purchased has been delayed. It will take approximately ten days to be added to the blockchain as proof of ownership.”

All software is hackable. That’s why we invented insurance.

The FDIC is free government insurance at your online bank of choice and your Visa or Mastercard debit card is accepted everywhere you want to be. PayPal & Venmo are practical and instantaneous for interpersonal financial transactions. India & China have government sponsored e-cash solutions that they encourage, monitor and enforce for private commerce requiring nothing more than a cellphone number. Moreover, the SEC regulates guarantees on qualified securities. Guaranteed securities include U.S. Treasury securities, such as Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, which are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Other examples are government-guaranteed agency securities, like those issued by the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), and certain guaranteed investment certificates from insurance companies or banks. The guarantee ensures a predictable return and a high degree of safety.

Privacy and Financial Repression

For the average person living in a constitutional democracy with reasonable privacy rights and stable rule of law, DeFi is more novelty than necessity. For people living in countries that lack these rights, DeFi is exceptionally valuable. The problem is that DeFi’s peer-to-peer architecture relies on access to the Internet, which at this point in history is increasingly easy to monitor and firewall. Thanks to continual advances in machine learning, it’s increasingly easy for national agencies to identify clear patterns of decentralized network activity. North Korea solves the problem by simply blocking all traffic to the the outside world. China’s state surveillance is incredibly difficult to bypass and the repercussions are simply not worth the trouble, especially when the digital renminbi is fast, efficient and ubiquitous for practical day-to-day commerce. If people want to engage in truly private commerce, paper currency is still the obvious choice, and the U.S. dollar is still the preferred vehicle. Approximately 45% of U.S. currency is held outside the United States, amounting to over $1 trillion. Repressive nation states would prefer to ban paper currency altogether, which would be ridiculous and virtually impossible, as there would be no alternative for individuals that lack or lose access to digital networks. This would only serve to encourage simple improvised IOUs or reversion to precious metals and stones. Credit and debit have always existed, and every human has a computer between their ears to remember who owes who what.

The Genius Act Isn’t

Under the new 2025 Genius Act, stablecoin issuers are required to back their coins with reserve assets and maintain redemption rights, but they are not obligated to pass earnings from those reserves—such as interest on Treasury securities or short-term debt—back to the holders of the stablecoins. Traditional Finance and startups are obviously very excited about this opportunity for issuers to earn substantial returns through asset arbitrage while users receive no yield, despite bearing counterparty and systemic risks. The Act defines stablecoins as bearer instruments, meaning whoever holds them owns them, but it does not classify them as securities, which means no investor protection rules that would normally apply to financial products generating yield.

This framework favors issuers by allowing them to profit from the float, similar to how wildcat banks once profited from deposits before interest-bearing accounts became standard, without offering transparency or fair compensation to users. Supporters claim this structure encourages innovation and keeps transaction costs low, but the lack of oversight may lead to concentration of wealth and risk in the hands of a few dominant issuers. The Genius Act thus legitimizes stablecoins as payment tools while leaving unresolved questions about fairness, accountability, and the distribution of financial gains.

With stablecoin market capitalization expected to exceed $2 trillion by 2028, and assuming average yields of 4–6% on permitted reserve assets, the arbitraged float revenue could reach $80–120 billion over a decade, none of which issuers are obligated to pass on to the bearers. If the market becomes competitive and isn’t dominated by a few players, yields may materialize to attract customers.

Stablecoins are not FDIC insured. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) provides deposit insurance for funds held in traditional bank accounts, such as checking and savings accounts, up to $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank. Stablecoins, however, are digital assets issued by private companies and typically backed by reserves like cash, Treasury bills, or commercial paper—not held in insured deposit accounts.

Some stablecoin issuers may claim that their reserves are held in FDIC-insured banks, but this does not mean the stablecoins themselves are insured. The insurance applies only if the funds are deposited in a qualifying account in the user’s name, which is rarely the case. So while stablecoins may be backed by assets held in regulated institutions, users are not protected by FDIC insurance if the issuer fails or the stablecoin loses value.