From their first lectures, university economics students are taught to treat inflation as a lurking threat. It’s an invisible force capable of distorting markets, eroding savings, and destabilizing entire economies. Professors emphasize its psychological grip on consumers and investors, the difficulty of forecasting it, and the painful trade-offs required to tame it. Case studies of hyperinflation in places like Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe are cautionary tales, reinforcing the idea that inflation is a specter that haunts policy decisions and economic models alike.

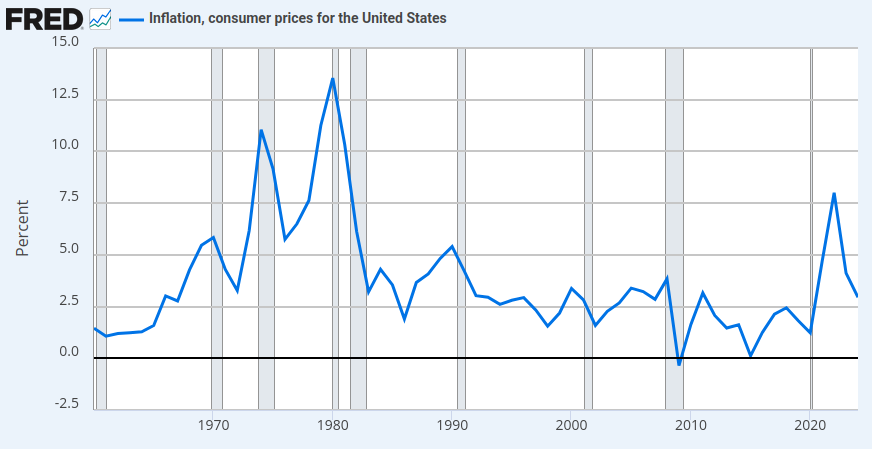

The 1970s in the United States were marked by a relentless surge in inflation that reshaped the economic landscape and strained the lives of millions. Triggered by a combination of expansive government spending, a shift away from the Bretton Woods currency system, oil price shocks from OPEC embargoes, and loose monetary policy, inflation soared to double digits by the end of the decade. Families felt the pinch as grocery bills climbed and mortgage rates skyrocketed, eroding purchasing power and forcing many to cut back on essentials. Businesses struggled to plan and invest amid volatile costs, with small enterprises particularly vulnerable to rising interest rates and shrinking consumer demand. Investors faced a punishing environment: traditional bonds lost value, and stock markets stagnated, leading to what economists dubbed “stagflation,” which is a toxic mix of inflation and economic stagnation. The crisis undermined confidence in government institutions and set the stage for a dramatic shift in economic policy in the 1980s, as the nation grappled with the painful consequences of unchecked inflation.

Paul Volcker was a towering presence at six foot seven with a frame that seemed built for endurance rather than elegance. His ever-present cigar jutted from his mouth that smoldered like his awkward silences. When he did speak, his voice was low and deliberate, each word weighed and measured, delivered with the slow certainty of someone who had no need to rush. In 1979 Volcker took office as the chairman of the Federal Reserve. He waged a bold and controversial war against runaway inflation. After raising the federal funds rate to around 17.6% in early 1980, the Fed briefly eased rates below 10% to counteract a recession. However, inflation remained stubbornly high, prompting Volcker to resume tightening in August 1980. This second round of rate hikes pushed the federal funds rate to its all-time peak of 19.1% in June 1981, triggering a deeper recession but ultimately breaking the back of inflation. By 1983, his policies had succeeded: inflation fell from double digits to below 4%, laying the foundation for sustained growth and a stronger dollar. Though criticized at the time for the pain his measures inflicted, Volcker’s legacy endures as the man who broke the back of inflation and reasserted the Fed’s credibility as an independent guardian of price stability.

Measurement Matters

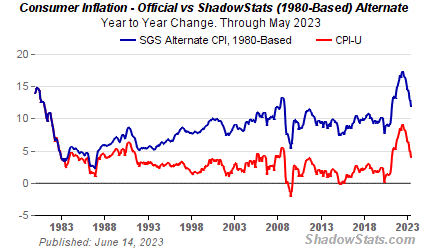

For most of the last 40 years, Americans have lived in a world where high inflation was something that happened in other countries. It was a ghost in the rearview mirror, a relic of the 1970s oil shocks and wage spirals. The Federal Reserve had tamed it, or so the story went. But that story was built on a subtle sleight of hand: the way inflation itself was measured had changed. In 1980, under pressure from rising entitlement costs and a public increasingly hostile to government spending, the Bureau of Labor Statistics began revising the Consumer Price Index. The CPI had once been a straightforward measure of how much it cost to maintain a constant standard of living. But that was expensive. So the government introduced “substitution”. If steak got too pricey, maybe you’d buy chicken. Then came “hedonic adjustments” in the 1990s, which accounted for quality improvements. A faster computer wasn’t more expensive, it was better. So the price hike didn’t count. By 1999, the CPI had become a measure not of what people paid, but of what economists thought they should feel about what they paid. In other words, the research methods that generate this critical data utilized by economists, investors and policymakers were more nuanced, subjective and susceptible to “exogenous influence.”

From 1980-2020 this new methodology wasn’t a significant problem. Globalization, a high U.S. trade deficit and a strong dollar drove down prices on everything from food to electronics. There was a remarkably long period of price stability. Low interest rates allowed easy credit for housing and discretionary spending. Much of this was possible thanks to China, India, Vietnam, Malaysia and other export-driven economies, following in footsteps of Japan’s post-war industrial policies: flooding the U.S. market with low cost goods and gobbling up dollars and bonds from the U.S. treasury, which allowed the government to continue deficit spending without any obvious or immediate repercussions. Neoliberalism seemed to be an unstoppable win-win — a rising tide that lifted all boats. Until it wasn’t.

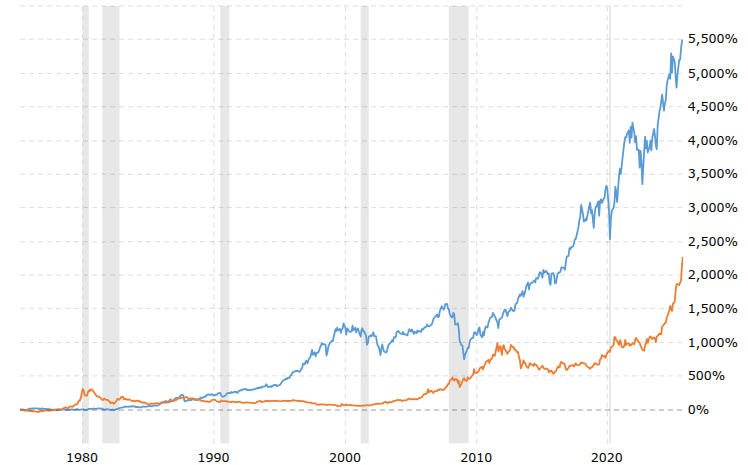

This matters because inflation is the denominator in every real return. If you bought the S&P 500 in 2020 and watched it climb 40 percent by 2025, you might feel rich. But if inflation over that period was actually 50 percent, as estimated using the pre-1980 methodology. You’re poorer in real terms. ShadowStats, a subscription source that tracks inflation using older methods, estimates that annual inflation since 2020 has ranged from 10 to 17 percent, far above the official numbers. Adjusted for this, the real return on equities has been flat or negative. If true, the supposed bubble in tech stocks, crypto, and real estate isn’t a bubble at all. It’s a desperate scramble to preserve purchasing power in a world where money is silently losing value.

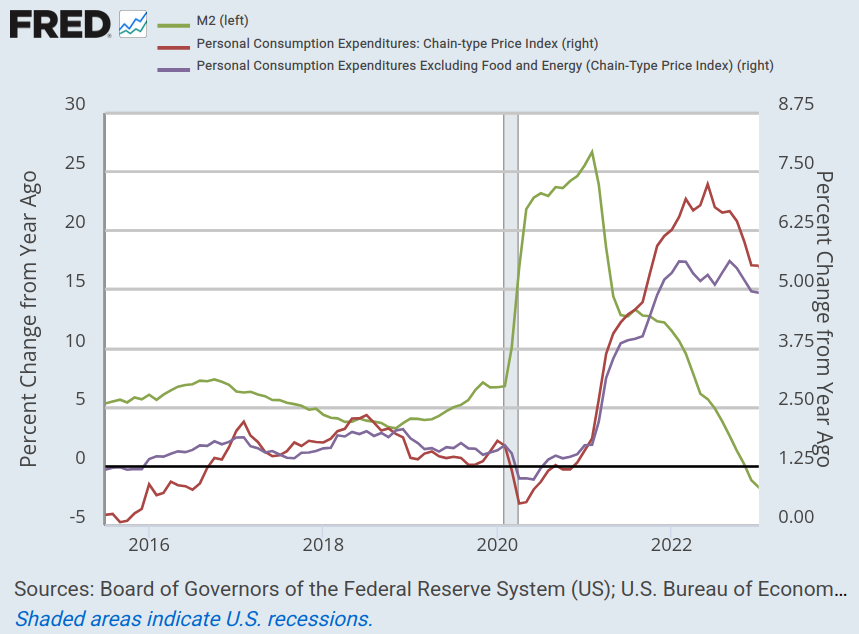

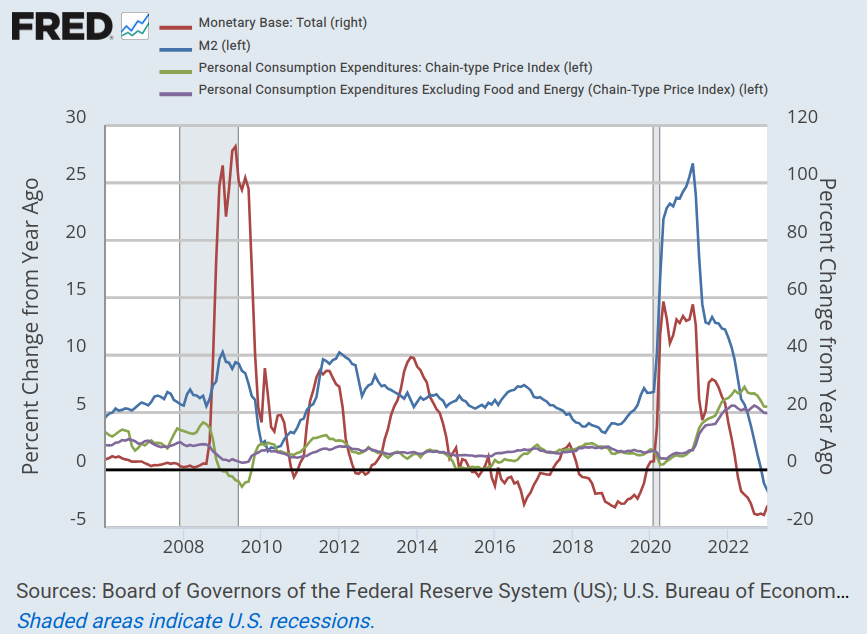

The pandemic spending spree only accelerated this. Governments around the world printed trillions to keep economies afloat. But unlike past crises, this one came after decades of suppressed inflation expectations. People didn’t see the danger because they hadn’t felt it. The result was a global monetary debasement that dwarfed anything seen since Bretton Woods. And now, the consequences are showing up not in headlines, but in the quiet decisions of central bankers. International reserves are shifting. The share of global reserves held in U.S. dollars has fallen steadily. Central banks in China, Russia, and even parts of the Middle East are buying gold—not for speculation, but for survival. Gold doesn’t have a central bank. It doesn’t get redefined. It just sits there, immune to hedonic adjustments.

For decades, the dollar was the anchor of the global financial system. But anchors only work if they hold. When inflation is understated, when real purchasing power erodes, when central banks quietly hedge their dollar exposure with gold and alternative assets, the message is clear: the world is losing faith. Not in markets, but in money itself. And that’s not a bubble. That’s a reckoning.

Using the measurement methodology from before 1980, the cumulative inflation rate in the United States from 2020 to 2025 is estimated to be between 35 and 50 percent, significantly higher than the official Consumer Price Index increase of about 20 to 25 percent. For example, in 2022, inflation under the 1980 method was estimated at 14 to 17 percent compared to the official rate of 8.7 percent. Annual inflation using the older approach ranged from 10 to 17 percent per year during this period, with ShadowStats and other sources providing alternate estimates that reflect the cost of maintaining a constant standard of living.

Studies from the Bank for International Settlements and the European Central Bank reveal that households tend to overestimate inflation, especially when prices of frequently purchased items like fuel and groceries rise sharply. This phenomenon is partly explained by salience bias, where consumers focus on noticeable price hikes while ignoring stable or falling prices. Additionally, inflation expectations are shaped by uncertainty and limited understanding of central bank policies. According to ECB research, individuals with low economic literacy or limited exposure to monetary policy tend to report higher inflation expectations, even when actual inflation is near target levels. A survey by the Bank for International Settlements across 29 countries found that households with greater knowledge of central banks and their mandates reported more accurate inflation expectations, underscoring the importance of clear communication from policymakers. These findings suggest that inflation is a psychological experience, filtered through perception, emotion, and trust in institutions.

Stagflation is the kind of economic condition that sounds like a contradiction until you live through it. It’s the worst of both worlds: rising prices and slowing growth. In the textbooks, it’s supposed to be rare. In reality, it’s what happens when the rules stop working. And right now, it may already be happening, quietly, behind the scenes of a stock market that looks euphoric and a labor market that feels tight but brittle. The signs are there. Inflation, when measured honestly, is running hot. Growth, once you adjust for that inflation, is tepid. Productivity is flat. Real wages are falling. And yet, the official narrative insists everything is fine.

The problem is that the tools we use to measure economic health were built for a different era. GDP growth looks solid until you strip out the inflation that’s been massaged by government agencies. Employment numbers look strong until you ask how many of those jobs are full time positions that pay enough to keep up with the cost of living. The illusion of prosperity is maintained by a statistical sleight of hand, and stagflation happens when that illusion starts to crack.

Tariff policies have played a curious role in this unfolding drama. On one hand, tariffs are supposed to protect domestic industries, create jobs, and rebalance trade. On the other, they raise costs for consumers and businesses alike. When the U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, the idea was to bring manufacturing back home. What happened instead was a spike in input costs and a scramble to find alternative suppliers. Some industries benefited, but many simply passed the costs on. In a low-inflation world, that might have been manageable.

The pros of tariffs are political and psychological. They signal strength, sovereignty, and a willingness to fight for domestic interests. They can protect strategic industries and reduce dependence on adversarial nations. But the cons are economic and structural. They distort markets, invite retaliation, and often fail to deliver the promised revival. In the context of stagflation, tariffs can exacerbate the problem by pushing prices higher without boosting real output.

What makes this moment so precarious is that most Americans don’t recognize it as stagflation because they’ve never seen it before. In the 1970s, it took oil shocks and wage spirals to wake people up. This time, it’s happening in slow motion. The dollar is losing purchasing power. Growth is sluggish. Asset prices are rising, but not in real terms. And central banks are caught between the need to tighten and the fear of collapse.

International banks see it. That’s why they’re moving away from U.S. Treasuries and back to gold. Not because they expect a return, but because they expect a reckoning. Gold doesn’t yield, but it doesn’t lie either. It doesn’t get redefined or revised. It just sits there, quietly reminding the world that value is not a matter of opinion. In a stagflationary world, that kind of honesty is rare. And increasingly, it’s in demand.

Professional analysts, economists, and fund managers and people whose livelihoods depend on parsing reality from illusion started to notice that the numbers. The official inflation rate said one thing, but the cost of living said another. The CPI claimed prices were rising at 3 percent, but rent was up 12, groceries 15, and insurance premiums were climbing like they had somewhere to be. It wasn’t just anecdotal. It was systemic. And so, they started looking elsewhere.

Inflation & Debt

Inflation favors debtors. If a debt has a 5% interest rate and inflation is 6%, the creditor is on the losing side of the deal in real terms. Governments have always had a complicated relationship with inflation. Publicly, they treat it like a disease to be cured. Privately, a little bit encourages spending, thus the typical target of 2%. Inflation is one of the most effective tools a government has to reduce its debt burden without ever admitting it’s doing so. When a government is too politically fractured or economically fragile to raise taxes, cut spending, or balance its books, markets have a way of balancing that equation in the form of inflation.

Governments borrow in nominal terms. They issue bonds, promise to pay back a fixed amount in the future. But if the value of money declines over time, the real cost of repaying that debt shrinks. A trillion dollars today might buy a fleet of aircraft carriers. Ten years from now, after sustained inflation, it might buy a few used tugboats. The debt gets paid, but the purchasing power behind it evaporates. It’s a stealth default, and it’s perfectly legal.

Carmen Reinhart, former chief economist at the World Bank, has written extensively about financial repression, the idea that governments use low interest rates and controlled inflation to erode the real value of debt. In her co-authored book This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Reinhart writes that “unexpected increases in inflation are the de facto equivalent of outright default, for inflation allows all debtors (including the government) to repay their debts in currency that has much less purchasing power than it did when the loans were made.” Inflation is the oldest trick in the book. It’s the way governments get out of debt without having to tell anyone they’re doing it. The trick only works if people don’t notice. That’s where the CPI comes in.

By understating inflation, governments can maintain the illusion of stability while quietly inflating their way out of fiscal trouble. Social Security payments, tax brackets, and interest on inflation-linked bonds are all tied to the CPI. If the CPI says inflation is 3 percent when it’s really 8, the government saves billions.

Take the United States. The national debt crossed $34 trillion in 2025, and the deficit remains stubbornly high. Congress is gridlocked. Entitlement reform is politically toxic. Tax hikes are a third rail. That leaves one option: inflate. And not just inflate, but do it quietly. The CPI, with its substitutions and hedonic tweaks, becomes the perfect tool. It tells the public that inflation is under control while allowing the government to pay back its debts with cheaper dollars.

Other countries are playing the same game. Japan, with its massive debt-to-GDP ratio, has embraced yield curve control and tolerated higher inflation. The UK, facing post-Brexit fiscal strain, has seen real wages fall even as nominal growth looks respectable. In both cases, the governments are using inflation to manage debt without triggering panic.

The people paying the price are the savers, the retirees, the wage earners. Their purchasing power erodes while the government’s balance sheet improves. It’s a transfer of wealth, not through taxation, but through time. And because it’s hidden in the numbers, many don’t realize it is happening.

Asset Prices During Inflationary Regimes

Gold and silver markets experienced a dramatic boom and bust cycle in the late 1970s and early 1980s, driven by economic turmoil, speculative fervor, and regulatory intervention. As inflation soared and confidence in the dollar eroded, investors flocked to precious metals as a hedge, pushing gold to a record high of $850 per ounce and silver to nearly $50 per ounce by January 1980. Much of silver’s meteoric rise was fueled by the Hunt brothers, wealthy oil magnates who attempted to corner the market by amassing over 100 million ounces through futures contracts and physical holdings. Their actions created panic and distorted prices, prompting exchanges like COMEX to change margin rules and impose limits on silver positions. When these new rules took effect, the Hunts were unable to meet margin calls, triggering a collapse in silver prices known as Silver Thursday in March 1980. Gold also fell sharply as Paul Volcker’s Federal Reserve raised interest rates to combat inflation, strengthening the dollar and reducing the appeal of non-yielding assets. The crash wiped out billions in speculative wealth and marked the end of a volatile chapter in commodity markets, underscoring the risks of leverage, manipulation, and policy shifts in shaping investor behavior.

Over the long run, stocks have outperformed gold in real terms, although gold has proven valuable during periods of economic stress. According to data from Morningstar and the World Gold Council, gold rose about 360 percent between 1990 and 2020, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average climbed more than 990 percent. When adjusted for inflation and dividends, equities have delivered stronger real returns. The S&P 500 Total Return Index, which includes reinvested dividends, has grown substantially over the past century, far exceeding gold’s performance.

However, gold has had standout periods. Between 2000 and the mid-2020s, gold increased nearly ninefold, while the S&P 500 rose about sixfold, according to Bloomberg and historical market data. Gold does not produce income and relies solely on price appreciation, which is why wealth managers often treat it as a hedge or portfolio diversifier rather than a growth engine.

All Weather Strategies

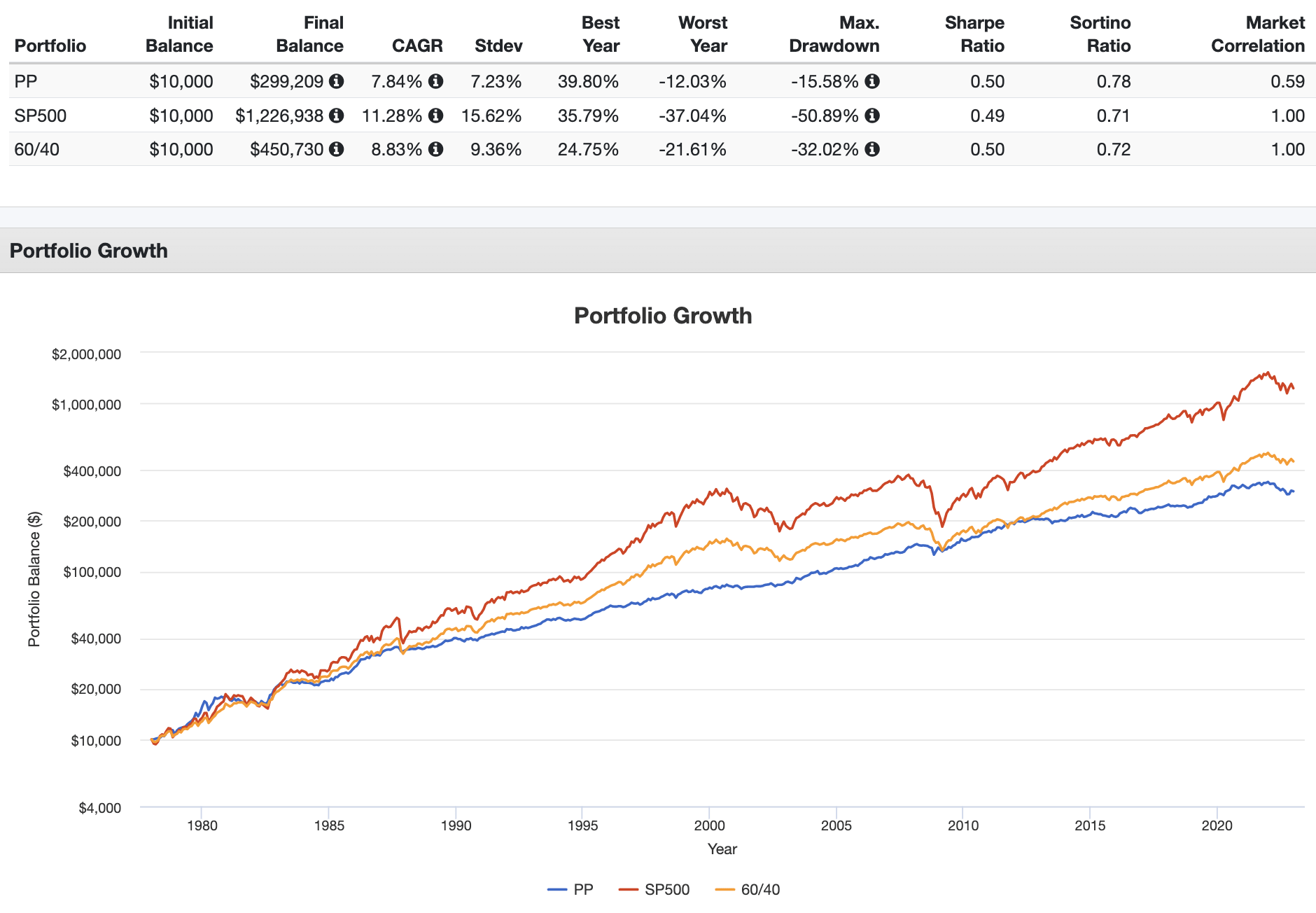

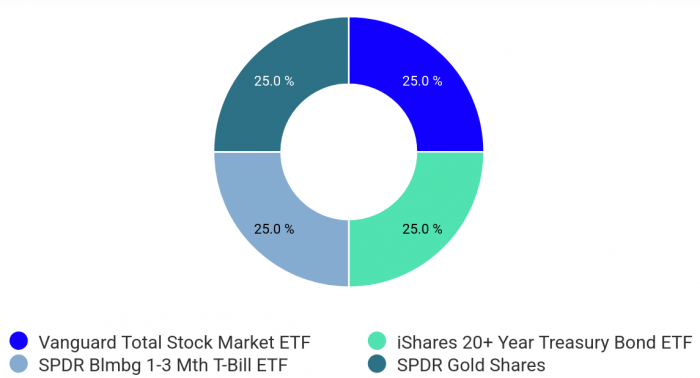

Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio, introduced in the 1980s and detailed in his book “Fail-Safe Investing,” is a classic and dead simple example of the principle of diversification across non-correlated assets. The portfolio allocates equal parts to stocks, long-term bonds, cash, and gold, each chosen to perform well in different economic climates such as inflation, deflation, recession, and growth. According to PortfoliosLab and OptimizedPortfolio.com, this simple four-asset strategy has delivered consistent long-term performance with lower volatility than traditional stock-heavy portfolios. For example, as of October 2025, the Permanent Portfolio posted an annualized return of 7.39 percent over the past decade, with relatively mild drawdowns compared to the S&P 500. While the returns are meager in comparison to more volatile assets, they may be attractive to high net worth investors who are more concerned with preservation than growth. When one asset class struggles, another often thrives, smoothing out returns and protecting investors from severe losses. Browne’s approach underscores the value of building portfolios that are resilient rather than reactive, especially in unpredictable markets. But when we consider the average rate of inflation since 2000 may actually have been 9%, such a conservative allocation would have had negative real returns. An intelligent investor must be willing to accept a higher allocation and risk premium in the equities of high quality businesses and alternatives in a well diversified portfolio. Securities such as quality bonds are a non-starter for younger investors. They are only useful as a basic hedge against volatility. Real returns on bonds are often flat or negative. Fixed income investors often choose to accept this trade off, as their primary objective is to avoid disastrous drawdowns and not run out of money during retirement.