Are markets still efficiently pricing assets?

The old story went like this: investors with data, insight, intuition and discipline would channel money toward innovation and growth, rewarding good ideas and punishing bad ones. Economists confidently called this market efficiency. While the market did exhibit cyclical patterns and periods of speculative overvaluation, valuations reverted to the mean. This is the risk premium of long-term equity investment. In the face of a relentless bull market where the underlying structures of flows and information inputs have changed, the disconnect between the old metrics, patterns and current prices has left many professional investors and pundits scratching their heads and hedging while retail bulls climb the proverbial wall of worry.

If it was ever true that markets were efficient systems of price discovery, it now functions mostly as a nostalgic reassuring justification for a system that seems to care less about allocating capital efficiently. What we have instead is a machine for taking all the excess liquidity from rampant government deficit spending and inflating all risk asset prices. Nearly anything that can be traded or assigned a monetary value is up. It’s a good time to invest in… anything. Since the great flood of pandemic M2, there’s been relatively positive price action on everything from Microsoft stock to Fartcoin. The pundits and finfluencers repeat the refrain, “is this a bubble,” or “is this another market top?” Successful professionals respond with, “valuations no longer matter.” It’s just talk. Nobody knows. This points to a divergence of assets as meme abstractions from economic fundamentals.

“Trees don’t grow to the sky,” they say. But there are substantial reasons to question whether the “new market” is like the old market, how it may be different and redress its underlying mechanisms.

Many analysts and economists have been asking variations of this question. In a recent forum hosted by Simplify Asset Management, Mike Green and David Einhorn posited a persuasive set of theories as to why markets are different.

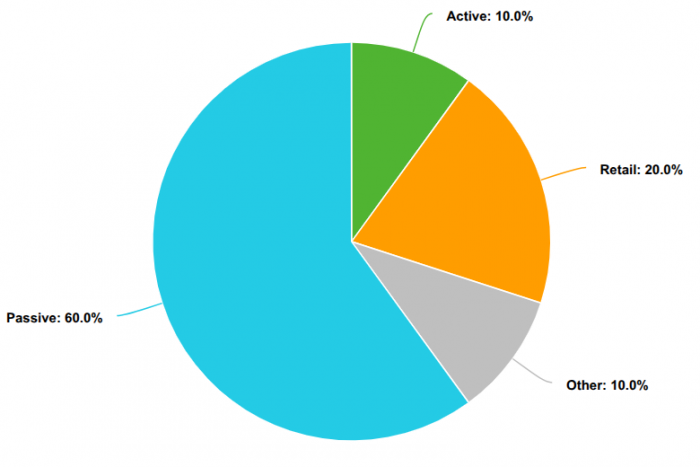

- The majority of market flow is now dominated by passive investment in the form of index funds.

- This passive flow has gradually pushed out professional active managers who historically engaged in long term evaluation and price discovery, plunging from 80% to just 10% of active trading.

- The preponderance of active management that remains is not qualitative. They are not analyzing businesses. These shops are either “closet indexing” or engaging in short-term arbitrage (hedge strategies, short-selling, front-running, and high speed trading).

- Simultaneously, the rise of speculative retail investors now accounts for 17% of trading volume — the largest percentage of active trading flow.

- Governments and world banks have perverse incentives to relax regulatory oversight, provide liquidity and tacitly insure the market against catastrophic failure to support the financial sector and the 401(k) retirement system.

They argue that all of this in concert has eclipsed a tipping point where the markets are no longer functioning the same way they did even a few years ago. Based on those percentages alone, this means that up to 60% of active trading flow is now retail, which has a dismal track record of low-quality information, panic selling and speculative valuation. Reasonable market efficiency as postulated in the Efficient Market Hypothesis rests on a simple idea: that all available information is rapidly reflected in the prices in an active highly liquid market. But that hypothesis was formulated when professional active traders contributed the majority of that information. Furthermore, the inventors of passive index investing always added the warning that it posed both a free rider dilemma and market efficiency would probably collapse into recursion at some unknown tipping point. Passive investing relies on the collective “wisdom of the market.” That is to say, passive indexes just copy the collective market price discovery of active professionals. While there are numerous academic papers that support some of Green and Einhorn’s claims with empirical research, the simple fact is that we don’t know, but the narrative is compelling. The more important question is, does it matter?

The “new stock market” may be less an efficient system for funding industry than a government-sponsored savings plan for the wealthy and professional classes. Millions of Americans depend on it to grow their retirement accounts, and this dependency has created a perverse political incentive: keep the market rising at all costs. Policymakers, terrified of triggering a downturn ahead of the next election cycle, have become the market’s unofficial custodians, pumping liquidity, manipulating yield curves, quantitative easing and issuing bailouts whenever the system hiccups. The Federal Reserve, the Treasury, and IMF all now operate as backstops to ensure that asset prices never fall too far, too fast. This creates an environment of increased hubris and risk taking. The irony is that the “free market” has become one of the most carefully monitored and tacitly insured institutions in American life, its performance central to both corporate expansion and personal financial survival.

While markets have always been dominated by top companies, the recent level of concentration is unprecedented. A handful of global technology corporations with low marginal costs and the cash flow equivalent of nation states have evolved into such an efficient oligopoly that they are capable of propping up the market and masking any “normal” lackluster returns. The feedback loop of passive flows exacerbates overvaluations while simultaneously causing a convergence of beta across all equities in the market index, which poses a significant problem for value investors. Thus it’s not the case that we can simply “pick stocks the old fashioned way” and avoid these structural problems without venturing into small cap and microcap territory outside the fringes of the index.

A valid question is what happens when most of these mega cap companies rapidly and aggressively pivot away from the low cost “money printing” business models that earned their top positions, into what amounts to more traditional industrial capital intensive business models to support costly and rapidly depreciating AI infrastructure, which will undoubtedly reduce free cash flow, buybacks and earnings at some future point? This calls into question their astronomic forward multiples, especially considering that nobody can answer where the revenue will come from, because these SAAS companies traversed that chasm once before in the 2000s until they realized the customer data was the product. The difference is traditional SAAS products have incredibly low marginal costs that only get better with scale. AI on the other hand is very expensive, which is captured best by Alphabet’s conundrum as it is forced to cannibalize its golden goose:

A traditional Google search costs minuscule fractions of a cent per query, while a Gemini AI search, depending on the model and usage tier, can cost anywhere from $0.02 to several dollars per million tokens, making Gemini significantly more expensive per interaction.

All the while, our “new market” increasingly serves as a critical public utility, but one with a uniquely American twist. Unlike water or electricity, which are regulated to ensure access and fairness, the financial system is allowed to operate with near-total impunity, so long as it generates enough wealth to keep the retirement accounts of the voting class afloat. This arrangement is not just fragile; it’s deeply cynical. After the 2008 crisis, there was a brief moment of clarity and recognition that markets were serving such a public function and ought to be treated accordingly. But that moment passed. Structural reform was minimal, inequality worsened, and the system reverted to its default setting: privatize the gains, socialize the risks, and call it freedom.

To understand this, let’s look back at the history of markets as the foundation of the retirement system in the United States.

The Retirement System

Before Social Security, retirement in the United States was less a phase of life than a slow descent into economic invisibility. The idea of “retiring” was mostly reserved for the wealthy or the fictional. For everyone else, it meant working until your body gave out, then hoping your children didn’t mind you sleeping in the pantry. It was and remains the gerontocratic arrangements of most traditional societies for millenia, but without the reverence, communal support, or ritualized storytelling. Instead, you got a cot in the corner and maybe a bowl of soup if the family budget allowed.

By the early 20th century, nearly half of elderly Americans lived in poverty, which is a polite way of saying they were broke, hungry, and largely forgotten. Then came the Social Security Act of 1935, a radical idea by American standards: that the state might actually help people survive after they stopped working. Funded through payroll taxes, it created a safety net that, for once, wasn’t just metaphorical. Elderly poverty dropped dramatically, and suddenly retirement became something more than a euphemism for dying slowly in your children’s attic. It had powerful latent effects on subsequent generational cohorts: greater freedom to relocate, reinvent, and follow economic opportunities.

In the 20th century, most American corporations also had this quaint little arrangement called the defined benefit pension. Many state and government employees still enjoy these programs. It was a sort of modern tribal compact: you worked for a company for thirty years, they promised not to let you starve in old age, and in return you pledged lifetime loyalty and didn’t ask questions about the CEO’s yacht and Lambo. Employers managed the investments, took on the risk, and retirees got a predictable and often generous income. It was a system built on trust, fiduciary duty, collective buying power and the assumption that corporations had some lingering sense of obligation to the humans who made their profits possible.

Then came the late 20th century. As corporations faced global competition and increasingly pilfered the balance sheets of their pension funds for interest-free cash, one day they looked at the rising costs of keeping their elders alive and said, “What if we just… didn’t? We could massively reduce costs.” In some cases, if the pension system was not responsibly organized as a separate managed investment trust, the companies were in such dire financial straits that funding the pensions out of profits would lead to bankruptcy.

Enter the 401(k), a brilliant piece of financial theater that shifted all the risk onto the worker while dressing it up as empowerment (which is ironically the brand name of a major retirement SAAS platform). Now, instead of a guaranteed pension, you got a tax-advantaged account and a vague sense of dread. Planning for retirement became a solo expedition through the jungle of market volatility, with nothing but a login and a half-read blog post to guide you. It was essentially replacing the power of a buyer’s collective operated by elite economists with a scratch-off ticket and calling it progress and freedom.

Boomers Are Not Ok

Baby Boomers get a bad rap these days. There’s a rampant misconception among younger people that they have “all the money” and life was easy peasey in their day. But the reality is far more nuanced.

Sociologists, ever the taxonomists of decline, have since sliced the baby boom generation into three neat cohorts: early boomers (1946–1954), mid boomers (1955–1960), and late boomers (1961–1964). Early boomers got the full postwar banquet of cheap housing, stable jobs, and pensions that actually paid out. Mid boomers got stagflation and the slow death of manufacturing. Late boomers? They got neoliberalism, globalization, and the privilege of watching their retirement plans evaporate into the ether of market abstraction.

Politically, this played out in predictable ways. Early boomers, raised on institutional trust and rotary phones, still believe the system works if you just follow the rules. Late boomers, having watched those rules rewritten mid-game, are understandably more skeptical. Financially, the divide is stark: early boomers built wealth through home ownership and pensions, while late boomers are more likely to be Googling “how to retire on $12,000 in an RV” and hoping Social Security doesn’t get rebranded as a lifestyle app.

The late boomers born between 1955 and 1964 were the first to be handed the 401(k) baton and told to pull themseleves up by their bootstraps and run with their new “freedom to choose.” Unfortunately, many didn’t know they were in a race, let alone that the finish line kept moving. It’s shocking when you learn that these early 401(k) plans that replaced defined benefit plans were often buried in an opt-in checkbox on an employee hire form, and the default investment they received if they did opt-in (unless they proactively set up a meeting with their company broker) was a money market fund which averaged around 1-2% annually. It’s not shocking then that nearly 40 percent have no retirement savings, and only 16 percent are projected to retire comfortably. It’s as if we took the old communal safety net, shredded it, and handed everyone a ball of yarn with instructions to knit their own parachute. The result? A generation caught between the mythology of postwar prosperity and the reality of financial precarity, clinging to personal savings and Social Security like relics of a society that once believed in collective care.

Generation X and the cohorts that followed were handed the keys to this new kind of retirement plan—one that came with a manual nobody read and a risk profile nobody understood. Unlike late boomers, who were blindsided by the collapse of defined benefit pensions, Gen X at least had the dubious privilege of growing up with 401(k)s and the illusion of control. They were told that if they just contributed early, diversified wisely, and believed hard enough in compounding returns, they’d be fine. What they got instead were two major market crashes, stagnant wages, ballooning debt, and the slow realization that “retirement planning” was code for “you’re on your own.”

Millennials and Gen Z, ever the digital natives, have embraced financial literacy, trading apps and meme stocks with the enthusiasm of a cargo cult. They know how to buy crypto on their phones, but many also know they’ll never afford a house. They’re financially literate in the way one becomes fluent in a language spoken only by their captors. The structural barriers like student debt, housing costs, and job precarity aren’t bugs in the system; they’re features. The system was never designed to help everyone retire. It was designed to reward those with access to the right institutions, the right credentials, and the right zip codes.

Market Participation

The U.S. economy has always operated in a stratified structure. That’s just good ol’ fashioned American Capitalism. Corporate employees at large firms receive stock options, retirement plans, and seminars on how to optimize their portfolios. They are the initiated, the ones allowed to participate in the “club” of market growth. Gig workers, freelancers, and small business owners are the uninitiated left to interpret the omens of economic survival with no tools and no guidance. The Federal Reserve’s own data confirms the imbalance: the top 10% of households own nearly 90% of equities, while the bottom half cling to the rest, if they have any investments at all. Is this just the natural Darwinian order of inequality or a caste system masquerading as meritocracy? That depends on which X feeds you follow.

And yet, there are those who argue, rather convincingly, that this is precisely what makes America great and why our companies’ equities dominate the market. That the brutal competition, the winner-takes-all ethos, is what fuels innovation and global dominance. In this view, the 20th century’s flirtation with progressive prosperity was a historical accident, or a brief detour from the natural order of oligopoly and struggle. To maintain its edge, the U.S. must return to a kind of gladiatorial capitalism, where citizens compete to serve the corporate pantheon, and the victors generate enough surplus to keep the rest from rioting. It’s not democracy. It’s not socialism. It’s Modern American Capitalism® coming to a country near you!

Capital Markets vs. “Capitalism”

Let’s start with a basic anthropological truth: markets are not some magical invention of capitalism. They’ve existed in every kind of society from Bronze Age Mesopotamia to medieval Islamic caliphates to the barter stalls of the Trobriand Islands. The idea that markets are inherently capitalist is like saying fire is inherently used for grilling steaks. Sure, it can be. But it’s also used for warmth, ritual, and occasionally burning down the neighbor’s hut when negotiations go south.

Now, take modern socialist countries like China and Vietnam. These are not places where markets were reluctantly allowed to exist in dark corners like rebellious teenagers sneaking out after curfew. No, these governments actively use markets as tools to advance national policy and public welfare. In China, for example, the government doesn’t just tolerate the stock market; it choreographs it. Capital flows are nudged, redirected, and occasionally shoved toward strategic sectors like green energy, semiconductors, or infrastructure. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominate the landscape, functioning less like profit-maximizing firms and more like bureaucratic organs with balance sheets. It’s capitalism with Chinese characteristics, which is a polite way of saying: “We’ll take the parts that work and ignore the rest.”

Vietnam, similarly, has embraced market mechanisms while keeping a firm grip on the steering wheel. The government directs investment toward social priorities such as education, healthcare, rural development all while while keeping retail speculation on a short leash. You won’t find Reddit-fueled meme stock frenzies here. Instead, you’ll find a system that treats the financial market like a public utility: something that should hum quietly in the background, delivering resources where they’re needed, rather than erupting into chaotic fireworks every time a billionaire tech bro or politician tweets.

You can be a patriotic ‘Merican and disagree with their style of “democracy” and lack of constitutional rights while simultaneously appreciating the remarkable outcomes they’ve achieved. China’s poverty rate dropped from over 88% in 1981 to under 1% by 2020, according to World Bank data. Vietnam’s GDP per capita has increased nearly tenfold since the early 1990s. These aren’t just numbers, they’re staggering transformations of economic power, standards of living and human well being. Documentary evidence abounds on YouTube that shows entire generations have shifted from subsistence farming and riding bicycles to an abundant urban middle-class consumer lifestyle that is practically identical to first world countries in the span of a few decades, all while the state played conductor to the market’s orchestra.

Financial markets thus also exist in socialist countries. But they’re not worshipped. They’re managed, shaped, and occasionally scolded like misbehaving children. The result is a system that treats finance as a means to an end, not an end in itself. It’s not perfect, but it’s a refreshing reminder that markets are tools, not gods, and that the real question isn’t whether you have a market, but what you use it for.

Contrast this with the evolving “free market” ideology in the West, which by all accounts resoundingly won the great battle of the twentieth century “isms” all while morphing into something quite different than the economic system built by the Americans who fought two World Wars and overcame the greatest economic depression in modern history. From Nixon to Clinton to Trump and beyond, the U.S. has spent money like drunken sailors on shore leave, loosened regulations, privatized nearly everything possible, financialized almost every aspect of our daily lives, exported dollars, treasury bonds and jobs abroad in exchange for cheap cars, raw materials, fuel and electronics, built elaborate structures like electronic stock exchanges, hedge funds, fintech apps and hoped that prosperity would descend from the heavens. And it did rain mana for many. For some it was riches fit for an emperor. However, for most it was a life of declining wages, no savings with a thin veneer of relative affluence through debt and low consumer prices. Without direction, markets tend to reward speculation, punish labor, and concentrate wealth in the hands of those who already have it. In the U.S., the top 10% of households own over 89% of equities, while the bottom 50% hold less than 1%. That’s not a market; it’s a ritual of exclusion.

The U.S. economy has been resilient since the 2008 financial crisis, and bounced back remarkably after the global pandemic. So how have the “free markets” that undergird our financial futures changed? Since U.S. companies have shifted the responsibility of retirement planning to the individual to save and invest, these changes matter.

Goodbye Professional Investors

Twenty years ago, the market was largely dominated by professional analysts and mutual funds whose primary strategy centered on identifying undervalued assets and investing in them long-term. While far from perfect, and incentivized to maximize profit, these investors generally operated with a clear valuation thesis, believing certain stocks, whether growth or value, were worth significantly more than their current market price. They might view a high-multiple stock as undervalued and estimate it should be priced 30% to 50% higher, holding onto it based on that conviction. This influence of this class of investors is on a fast track to collapse.

The rise of passive index investing, especially through 401(k) plans now accounts for the majority of trading. Passive index funds and ETFs account for approximately 53% of the U.S. stock market flow. Passive funds attracted $886 billion in net inflows in 2024, while active funds experienced a $166 billion outflow. Over the past ten years, passive funds have steadily gained market share, increasing from 30% to 53%, and have absorbed a cumulative $5.8 trillion in net new money, compared to a $2.5 trillion outflow from active funds.

This trend toward passive highlights a broader transformation in investor behavior, where cost efficiency, simplicity, and long-term growth potential have made passive vehicles like ETFs and index funds the preferred choice for many market participants.

The problem is that active management is what made markets efficient systems for price discovery. Active managers assess company fundamentals, industry trends, and macroeconomic factors to determine whether a stock is overvalued or undervalued. Their buying and selling decisions reflect informed views on valuation, which helps adjust prices toward more accurate levels. This process contributes new information into asset prices and challenging mispricings.

Markets were once imagined as great engines of collective intelligence—places where careful analysis and spirited debate would converge to produce something resembling truth. In 1995, active managers still dominated the landscape, accounting for 80% of trading, armed with research departments and valuation models, all in service of a quasi-moral ideal: that prices should reflect something real. Fast forward to today, and that figure has collapsed to 10%. In their place, we find a growing army of speculative retail traders, up from 10% to 17%, armed not with training or theory but with apps, memes, and vibes.

The few remaining professionals have retreated into algorithmic pod shops, quant strategies, momentum chasers, none of which pretend to care about what a company actually does. The idea that markets exist to allocate capital efficiently has become quaint, almost folkloric. Now, when a stock enters an index, the production of fundamental information actually declines due to distortions from passive indexes. The most influential data isn’t about earnings or innovation, but about order flow: who’s clicking what, and how fast. In other words, the market has become a theater of signals divorced from substance, a ritual of motion where meaning once lived.

Rise of The Retail Investors

In the world of modern finance, we are witnessing a strange inversion of purpose. Robinhood, a platform marketed as democratizing access to markets, routes its users’ trades not to public exchanges but to Citadel Securities, a private firm that pays Robinhood for the privilege of executing those trades. This arrangement, known as payment for order flow, allows Robinhood to offer commission-free trading while Citadel profits from the bid-ask spread—a tiny sliver of difference between what buyers pay and sellers receive. It’s a system that appears frictionless, even benevolent, until one realizes it’s built on a quiet extraction of value from the very users it claims to empower. The irony is that this setup mirrors the logic of feudal toll collection more than any ideal of market transparency.

Meanwhile, the notion that markets exist to reflect intrinsic value has all but vanished. What remains is a theater of algorithms and momentum trades, where positions are adjusted in milliseconds based on signals that have nothing to do with what a company actually does. Institutional investors, once the supposed stewards of rational capital allocation, now chase volatility like everyone else. Fundamental analysis has become a kind of quaint ritual, like reading tea leaves in an age of satellite weather forecasting. Nobody bothers with valuation because it simply doesn’t pay. The market has become a game of reflexes, not reflection—a place where meaning is irrelevant and speed is everything.

The Securities and Exchange Commission, once imagined as a guardian of financial integrity, has quietly retreated into a role more akin to a ceremonial referee, occasionally blowing the whistle on petty infractions like overheard insider tips, while ignoring the deeper structural manipulations that define corporate behavior. Its decline in regulatory enforcement isn’t accidental or due to lack of capacity; it’s the outcome of a deliberate political calculus. Under leadership like Chairman Christopher Cox, the agency embraced a philosophy that equated accountability with instability, arguing that punishing fraud might upset shareholders and, by extension, the sacred equilibrium of the market. The SEC became a kind of backstage custodian, sweeping up after collapse rather than preventing it. It no longer questions depreciation schedules or challenges accounting sleight-of-hand. Instead, it waits for bankruptcy to make enforcement palatable. What we’re left with is a system where regulation exists mostly in theory, and the idea of proactive oversight has been abandoned, not through neglect, but by design.

Today, markets are treated less as mechanisms of economic coordination and more as a kind of public utility, or a retirement delivery system for passive investors funneling wages into index funds and 401(k)s. This transformation, while socially useful, has hollowed out the very idea of financial expertise. The broker, once a counselor tasked with understanding a client’s goals and recommending suitable investments, has been replaced by platforms like Robinhood, which invite anyone to speculate freely, regardless of knowledge or consequence. Regulation has not so much failed as been reimagined out of existence. The accredited investor framework lingers like a vestigial organ, even as political momentum builds to dismantle it entirely. What we’re witnessing is not deregulation but a cultural shift that treats oversight as paternalism and celebrates the freedom to lose money as a moral right.

In today’s deregulated environment, financial markets have become a space where speculative retail behavior faces little to no oversight and suitability standards have largely disappeared. Individuals can earn income through gig work and immediately invest in high-risk options without guidance or restrictions as if it is just online gambling. Although some private investment vehicles still require accreditation, the broader trend favors unrestricted access, with minimal interest in restoring tighter controls. One curious exception is the ongoing ban on online poker in certain areas, which contrasts sharply with the freedom granted in financial speculation. When concerns arise about high market valuations, the idea that fewer stocks justify higher prices is dismissed. There is no shortage of investable assets, and rising valuations often lead to new offerings through IPOs, cryptocurrencies, and alternative investments. Given the scale of capital markets and their size relative to GDP, supply constraints do not provide a credible explanation for elevated prices.