“The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.”

— Hans Hofmann.

The Target Date Fund that provides the foundation for the modern 401(k) retirement plan may seem like one of the most boring topics possible, but its origin story turns out to be a surprising tale that begins in the ivory towers of academia, winds through the corridors of pension consulting, takes some interesting detours through the sets of Star Wars and Kubrick’s The Shining and ends up as the most popular portfolio strategy in almost every employee’s 401(k). Today it’s a financial product so ubiquitous that most people don’t even realize it was a revolution in democratized retirement planning for millions of people in the U.S. and beyond.

After spending more time with spreadsheets and market data backtesting tools than a T. Rex spent terrorizing the Cretaceous, the author emerged from the jungle of frustrating data with a surprising revelation: while the Target Date Fund may be what you get in your 401(k) when you have absolutely no idea what to do, its arguably also the smartest option for an intelligent investor who’s prepared to admit that beating the market and managing a portfolio over decades is exceptionally difficult — especially while juggling a life and full time job. It’s the financial equivalent of a time-traveling Archelon (an ancient tortoise) — an underappreciated marvel backed by decades of research.

While other asset allocation strategies require constant tweaking, emotional resilience, and possibly a NASA-grade simulation lab, the Target Date Fund rebalances automatically, appropriately adjusts your risk exposure over time, and the low cost passive options somehow manage to outperform many actively managed mutual funds with inscrutable, abstruse prospectus sheets crammed with scores of other equally abstract holdings.

Consider how extraordinary the Target Date Fund is. An investor can select a fund labeled with their retirement year — 2035, 2050, maybe 2065 — and can move on with a surprising level of confidence that it will achieve positive results based on the target. It’s not (yet) some precise A.I. that collects all the (probably substantial) data on you from your LinkedIn and social media profiles, credit rating agencies, or even from your employer in the 401(k) plan it typically serves in order to tailor the optimal investment strategy just for you. In fact, many of the best offerings are dead simple portfolios using a combination of four to twenty low cost index funds that follow a rules-based approach grounded in extensive quantitative research. This single choice sets in motion a statistically elegant solution to one of the most complex problems in personal finance: how to allocate assets over a lifetime without knowing anything about the investor’s income, net worth, savings rate, or debt obligations. The fund doesn’t ask for a salary figure, a mortgage balance, or even a risk tolerance questionnaire. It doesn’t need to. It simply uses one data point — the expected retirement year — and builds a glide path that works astonishingly well for most people — and there are infinite alternatives that are worse.

While implementations of Target Date Funds or Target Retirement Funds vary across providers and often differ between institutional and investor classes, they all share the concept of the glide path that gradually hedges risk over time via rebalancing the asset allocation. Vanguard and Fidelity utilize their own indexing methodologies and Standard & Poors offers an index that tracks the relative performance of leading TDFs to provide an industry average.

Glide, Balance and Flow

The three key features of any Target Date Fund are automatic glidepath, rebalancing, and dollar cost averaging — which offer significant benefits and are exceedingly difficult and time consuming to manage yourself.

Glidepath

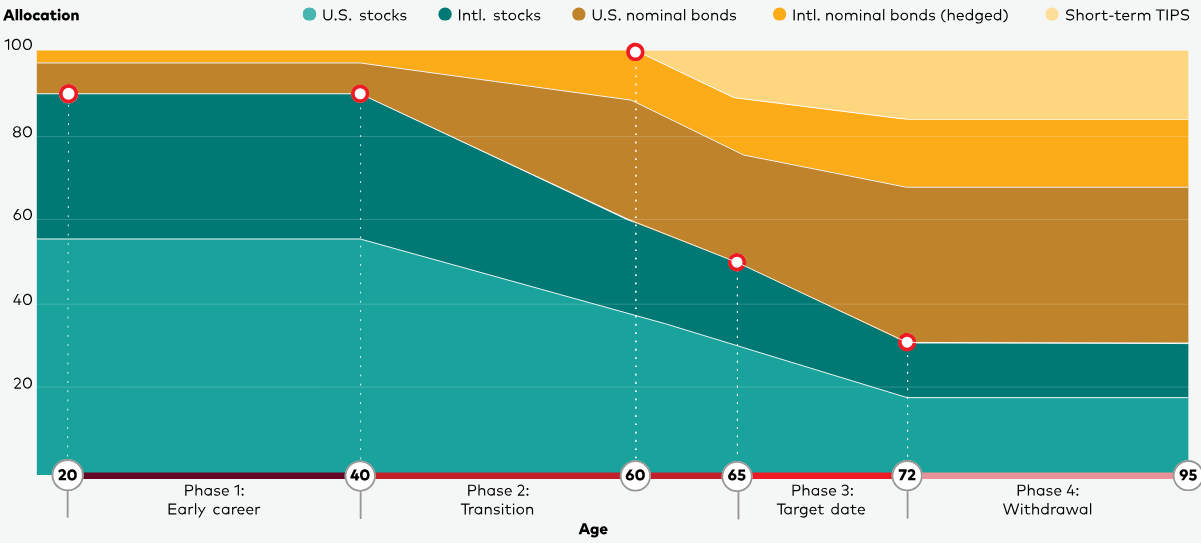

A target date fund glide path is an investment roadmap that dictates how a fund’s asset allocation changes over time, gradually shifting from higher-risk assets like stocks to lower-risk assets like bonds as the target retirement date approaches. This “glide” helps to balance the desire for growth in early years with the critical need for capital preservation and stability in later years, managing risks such as market volatility and longevity risk.

Many investors in their late 40s and 50s who piled into aggressive growth tech stock funds in 1998-2000 lost substantial retirement savings and most didn’t get back above water until 13-14 years later. Thanks to the glidepath, folks approaching retirement who invested in TDFs were adequately hedged and did fine during that period and were able to retire according to plan. In fact, it was the GenX and early millennial cohorts that were hit the hardest because inflation-adjusted equity market returns were flat or negative between 2000-2010 during their early career phase. Fortunately, that cohort still had time to benefit from the subsequent bull market during their prime earning years that’s still going strong today.

Rebalancing

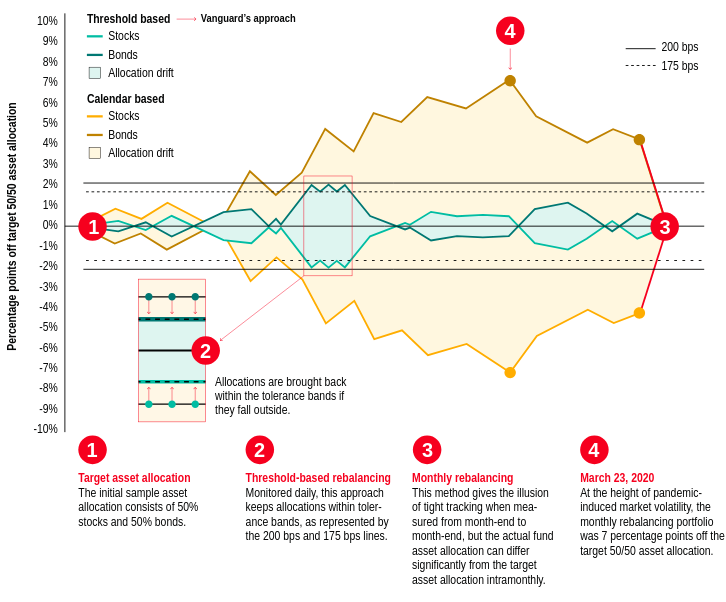

Automatic portfolio rebalancing is a process that routinely adjusts a fund’s asset allocation back to target percentages to manage risk, maintain your desired investment strategy, and prevent unintended shifts due to market performance. By automatically selling assets that have grown beyond their target and buying assets that have fallen below their target, it helps keep your portfolio aligned with your risk tolerance and financial goals, even without manual intervention. Rebalancing a portfolio of non-correlated assets buys when prices are lower and sells when valuations are expensive. Even though bonds offer lower returns, they are price stable and store excess profits from equity bull markets, and provide “dry powder” during bear markets.

Flow: Dollar Cost Averaging

Because Target Date Funds are designed with a tax advantaged 401(k) account in mind, dollar cost averaging is automatic, as you will typically contribute a portion of your monthly income to your retirement plan. This method averages out your purchase price across the portfolio over time, which helps to reduce investment risk and avoid the pitfalls associated with trying to time the market. DCA is a disciplined approach that removes emotion from investing and avoids concentrating buy orders just before an unpredicatable large drawdown.

The Uncertainty Principle

When it comes to statistical probability in a world of substantial uncertainty and risk over time, sometimes simple is not only better, but more transparent. The random nature of the market can be incredibly deceptive, where consistent “average” performance appears unimpressive in the short term, but is exceptional long term. Slow and steady wins the race.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb notes in his seminal 2001 work, “Fooled By Randomness,” that humans underestimate the role of randomness in life and decision-making, mistakenly attributing success to skill rather than chance. Taleb emphasizes that outcomes are often substantially influenced by random events, and we tend to overlook the significant impact of luck while focusing on the visible winners.

Investors who attempt to “beat the market” with a model or thesis are faced with what’s known as Bonini’s Paradox, which states that as a model of an infinitely complex system involving randomness attempts to become more realistic, it also becomes as difficult to understand as the real thing and more prone to inaccuracy. The lesson is that sometimes it is better to let a simple statistical model operate with its “good enough” quirks than to risk badly breaking it entirely in the pursuit of an unreachable state of perfection.

This is where the TDF shines. It leverages the power of broad statistical probability and lifecycle investing principles to create a dynamic asset allocation strategy. Younger investors have more “human capital” — the present value of their future earnings — and can therefore afford to take more market risk. As retirement approaches and human capital diminishes, the fund gradually shifts toward capital preservation. Vanguard’s research team, including Scott Donaldson and Francis Kinniry, has shown that this approach balances market, inflation, and longevity risks in a way that is both highly efficient and transparent over the investor’s life cycle.

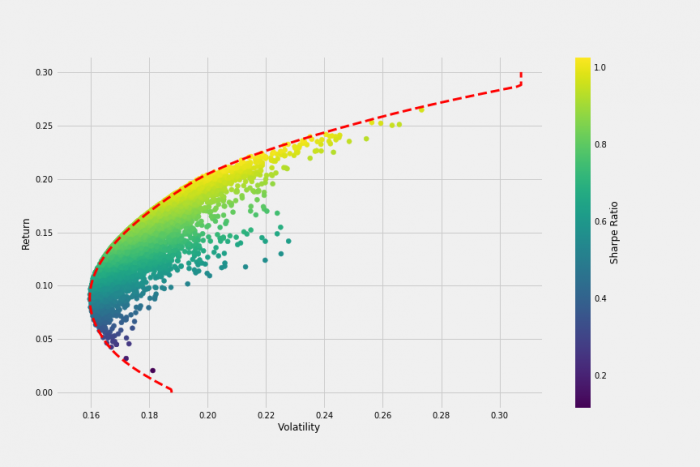

Vanguard’s glide path, for instance, starts with a 90% allocation to equities for investors 40 years from retirement, gradually tapering to just 30% equities post-retirement. This isn’t arbitrary: it’s grounded in Modern Portfolio Theory and refined through decades of empirical data. The expected return of each portfolio stage is calculated using weighted averages of stock and bond returns, and the glide path is optimized to maximize long-term growth while minimizing volatility near retirement. A 2040 fund today, for example, might hold 80% stocks and 20% bonds, yielding an expected return of 6.2% annually based on historical averages.

What’s even more remarkable is how well this generalized strategy performs across diverse populations. Vanguard’s 2019 study found that TDFs consistently improved retirement readiness, even among investors with vastly different financial profiles. The funds helped reduce the most deleterious investor behavioral errors, like panic selling during downturns or failing to rebalance. It provided a managed portfolio strategy for those who lacked the time or expertise to build one themselves.

Recent data from Sway Research shows that the market for TDFs has grown to over $4.7 trillion in assets by mid-2025, with Vanguard alone managing $1.6 trillion. This explosive growth isn’t just a testament to marketing: it reflects the statistical power of a well-designed glide path. Even as new products emerge with built-in income features and annuity overlays, the core principle remains the same: use time as a proxy for risk tolerance and let probability do the heavy lifting.

Morningstar’s 2025 Research

Morningstar’s latest research highlights that target-date funds have significantly outperformed expectations over the past 15 years, particularly for investors in 2025-dated funds that were at the critical point in their glide path when investors hit their target date:

- Asset Growth: Target-date strategies surpassed $4 trillion in assets by end of 2024, growing at an annualized rate of over 30% since 2009.

- Performance: 2025 target-date funds returned an average of 7.3% annually, beating the 6.3% expected return modeled in 2010.

- Resilience: Even during the early 2025 market downturn (the S&P 500 fell 18.6%), these funds only declined 7.6%, showcasing their defensive structure.

- Fee Reduction: Fees dropped to an asset-weighted average of 0.29% in 2024, down 48% over the past decade—boosting investor returns.

- Investor Impact: Workers retiring in 2025 who consistently invested in these funds benefited from dollar-cost averaging and long-term compounding.

In a world where most financial decisions are riddled with complexity and personal nuance, the TDF offers a rare kind of simplicity that has actually been proven to work. It’s a quiet triumph of academic theory, behavioral insight, and statistical design: one that millions of investors benefit from without ever realizing the genius behind it.

So who came up with this elegant design that probably contributes the most flow into today’s market? The story may surprise you.

Academic Research

William F. Sharpe’s journey to becoming the intellectual father of the Target Date Fund began not in finance, but in medicine. Born in Boston in 1934 and raised in California, Sharpe originally enrolled at UC Berkeley with plans to become a doctor. But after a year of science courses, he realized his interests lay elsewhere. He transferred to UCLA and declared a major in business administration, only to find accounting uninspiring. It was microeconomic theory that captivated him. That pivot would change the course of investing history.

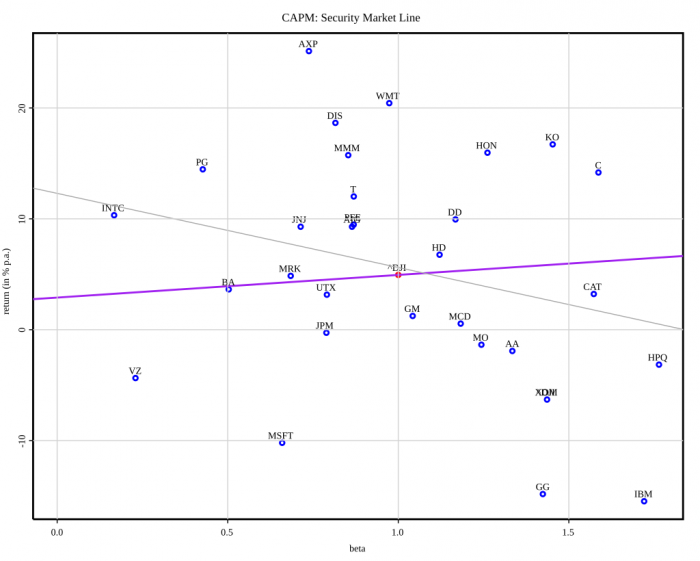

Sharpe earned his BA in economics in 1955, followed quickly by an MA in 1956 and a PhD in 1961, all from UCLA. His intellectual development was shaped by two towering figures: Armen Alchian, a rigorous economist who taught him to question everything and build arguments from first principles, and J. Fred Weston, a finance professor who introduced him to the groundbreaking work of Harry Markowitz on portfolio theory. Weston encouraged Sharpe to seek out Markowitz at the RAND Corporation, where Sharpe was working as an economist. Markowitz, though not officially his advisor, became a mentor and sounding board as Sharpe developed his dissertation: a single-factor model of security prices that would evolve into the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM).

Sharpe’s CAPM was revolutionary. It formalized the relationship between risk and return, showing that the expected return of an asset depended on its sensitivity to market movements, known as beta. This model became a cornerstone of Modern Portfolio Theory and earned Sharpe the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1990. CAPM was later superseded by, and considered an idealized variation of Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT), which underscored CAPM’s utility in portfolio design for pension planning.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Sharpe held academic positions at the University of Washington, UC Irvine, and Stanford, where he became the Timken Professor of Finance. He also consulted for firms like Merrill Lynch, Wells Fargo, and the RAND Corporation, gaining firsthand exposure to the challenges faced by institutional investors. It was during this period that Sharpe began to think more deeply about the limitations of traditional portfolio optimization: especially in the context of pension funds, which had long-term liabilities that weren’t being accounted for in standard models.

This line of thinking led him to collaborate with Larry Tint, a fellow academic and practitioner who shared Sharpe’s interest in bridging theory and practice. Together, they published the seminal 1990 paper “Liabilities: A New Approach,” which proposed integrating future liabilities into the asset allocation process. It offered a flexible framework that allowed pension managers to balance return objectives with the need to meet future obligations: a concept that would later evolve into the glide path structure of Target Date Funds.

Before Larry Tint crossed paths with Bill Sharpe, he had already built a formidable foundation in both academia and professional finance. Tint earned his undergraduate degree in economics from Haverford College, a liberal arts institution known for its rigorous intellectual environment and emphasis on ethical leadership. He then went on to receive an MBA in finance and operations research from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania: one of the most prestigious business schools in the world. This dual focus on finance and quantitative analysis would become a hallmark of Tint’s career.

Professionally, Tint held a series of influential roles at major financial institutions. He worked at Merrill Lynch, Wells Fargo Investment Advisors, Wilshire Associates, and Trust Company of the West. These positions gave him deep exposure to institutional asset management, portfolio construction, and the operational challenges of managing large pools of capital. At Wells Fargo, in particular, Tint was involved in developing investment strategies for retirement plans and pension funds, which required balancing long-term liabilities with market risk: a theme that would later become central to his collaboration with Sharpe.

Tint’s experience managing institutional money and his academic grounding in operations research made him uniquely suited to tackle the complex problem of liability-driven investing. When he eventually met Sharpe, their shared interest in bridging theory and practice would lead to a partnership that helped reshape retirement planning for millions.

Sharpe and Tint formalized their collaboration by founding a consulting firm called Sharpe Tint. They advised pension funds on how to align their investments with their obligations, using Sharpe’s mathematical models and Tint’s practical insights.

But the ivory towers of academia and the R&D teams at large corporations are laboratories where many great ideas form, but are often so obfuscated by impenetrable equations, charts, and academic techno-babble that they quietly wither in some bound tome of peer reviewed papers in the basement archives, lost forever in obscurity.

Enter Don Luskin, the maverick wildcard in our story.

Before Donald Luskin ever set foot in a boardroom or scribbled out the blueprint for a financial innovation, he was living a life that could only be described as part economist, part Hollywood rogue, and part philosophical firebrand. If you were casting a movie about the invention of the Target Date Fund, Luskin would be the character who walks in halfway through the film wearing sunglasses, quoting Ayn Rand, and casually mentioning that he once worked on Star Wars and The Shining. And yes, that actually happened.

Luskin’s academic career was brief but dramatic: he attended Yale in the early 1970s, but dropped out after just a year. Why? Because, as he later put it, he wanted to “rejoin the real world as soon as possible.” Most people leave Yale to join hedge funds or write novels. Luskin left to help design treasure hunts and consult on blockbuster films. He worked with Lucasfilm on Star Wars, and with Warner Bros. on Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining: which, if you think about it, is a pretty good metaphor for the volatility of financial markets. He also contributed to Altered States, a film about sensory deprivation and hallucinations, which feels oddly appropriate for someone who would later pioneer index options trading.

During this Hollywood phase, Luskin was helping shape the economics of merchandising and production logistics. He had a knack for turning abstract ideas into tangible systems, whether that meant designing a treasure hunt that became the Disney movie Midnight Madness, or helping studios understand the cost-benefit calculus of shooting in remote locations. It was a strange but fitting prelude to his later work in finance, where abstract models and real-world outcomes collide daily.

Luskin wasn’t just a creative consultant with a taste for cinema: he was also a devoted follower of Ayn Rand, the Russian-American philosopher and novelist who championed individualism, free markets, and the moral primacy of self-interest. He saw markets not just as mechanisms for wealth creation, but as arenas for individual expression and rational decision-making. He believed in the power of the individual investor, the elegance of free-market solutions, and the folly of bureaucratic meddling. This ideological foundation would later inform his approach to designing investment products that were simple, transparent, and rooted in rational choice.

By the late 1970s, Luskin had pivoted into finance, launching a hedge fund while working as an options market maker on the Pacific Stock Exchange. He helped pioneer index options trading, executing the very first OEX contract on the Chicago Board Options Exchange. In 1984, he joined Jefferies & Co., where he invented POSIT: a revolutionary crossing network that allowed institutional investors to trade entire portfolios anonymously. POSIT was later spun off into Investment Technology Group, a publicly traded company.

By the end of the 1980s, Luskin had become vice chairman of Wells Fargo Investment Advisors, just as it merged with Nikko Securities to become Wells Fargo Nikko Investment Advisors. It was here, in the crucible of institutional finance, that Luskin would meet Larry Tint: and the story of the Target Date Fund would begin to take shape.

The genius of the Target Date Fund lay in its simplicity. They combined Sharpe Tint’s pension glide path with a portfolio of mutual funds. Investors didn’t need to understand Modern Portfolio Theory or liability matching. They just picked a fund labeled with their retirement year: 2040, 2055, whatever — and the fund would do the rest.

One can imagine the conversations between Tint and Luskin during those early days. Tint, reserved and analytical, would caution against oversimplification. “We must ensure the glide path reflects the actual liability structure,” he might say, adjusting his glasses. Luskin, animated and persuasive, would counter, “Larry, people don’t want complexity. They want trust. We give them a timeline, a promise. That’s what sells.”

Their collaboration led to a patent, and soon the Target Date Fund was born. But it wasn’t until the Pension Protection Act of 2006 that things truly took off. The law created a category called Qualified Default Investment Alternatives, allowing employers to automatically enroll workers into retirement plans using products like Target Date Funds. Suddenly, these funds weren’t just smart — they were legally protected defaults. Adoption skyrocketed.

Major financial firms jumped on board. Vanguard, BlackRock, Charles Schwab, T. Rowe Price, Fidelity all launched their own Target Date Fund series. By 2024, assets in these funds had surpassed $4 trillion. Vanguard alone added over $35 billion in a single year. The growth was staggering, and it showed no signs of slowing.

But the real magic of TDFs wasn’t just in their popularity: it was in their effectiveness. Studies showed that by aligning asset allocation with time horizon, these funds improved retirement outcomes across the board. They reduced downside risk for near-retirees during market crashes and captured long-term growth for younger investors. In the 2020 market downturn, long-dated funds lost less than broad equities, while near-retirement funds were even more protected. The statistical probability of success was simply higher when risk was managed dynamically.

And so, the story of the Target Date Fund is one of unlikely convergence. A Nobel laureate, a pension strategist, and a Hollywood consultant-turned-financier came together to solve one of the most pressing problems in personal finance. Their invention now quietly powers the retirement dreams of millions, embedded in the default settings of 401(k) plans across the country. It’s a strange tale, but a profoundly important one: and it’s still unfolding with statistical research on the behavioral risk and the importance of the Global Market Portfolio.

Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!

If there’s one overarching reason why the Target Date Fund is the often the best option for even the seasoned investor, it’s behavioral risk. It’s the top reason for poor investment outcomes. The field of behavioral finance studies how psychological biases and emotions influence financial decision-making, showing that investors are rarely the rational agents assumed by traditional economic theory. These predictable human tendencies can result in costly and self-defeating behaviors.

Common psychological biases

- Loss aversion: The tendency for the pain of a loss to be felt more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. This bias causes investors to hold onto losing investments for too long, hoping for a recovery, while selling winning investments prematurely to lock in gains. This contradicts the sound investing principle of cutting your losses and letting your winners run.

- Overconfidence: An excessive belief in one’s own judgment and abilities. Overconfident investors may believe they can consistently beat the market, leading to excessive and high-risk trading. This frequent trading can increase transaction costs and often results in lower returns compared to a less active strategy.

- Herd mentality: The tendency to follow the crowd rather than relying on independent analysis. This behavior is driven by a fear of missing out (FOMO) and can amplify market bubbles and crashes as investors rush to buy high and sell low.

- Confirmation bias: The desire to seek out and favor information that confirms pre-existing beliefs, while ignoring contradictory evidence. This can prevent investors from objectively analyzing an investment, leading to poor decisions.

- Anchoring: An over-reliance on the first piece of information received when making decisions. An investor might fixate on a stock’s initial purchase price, even if it is no longer relevant to its current market fundamentals. This can prevent them from correctly adjusting their views as new information emerges.

- Recency bias: Giving more weight to recent events while disregarding long-term trends. A string of recent good performance can cause an investor to incorrectly assume it will continue, leading them to buy at a peak.

Impact on personal investment performance

These behavioral pitfalls directly undermine an individual’s financial success.

- Underperformance: Studies have shown that emotional decision-making causes average individual investors to significantly underperform market benchmarks over time. By selling in a panic during market downturns and chasing returns during market highs, investors destroy wealth instead of building it.

- Lack of discipline: Many investors fail to establish and stick to a consistent investment plan. Instead, they let short-term market fluctuations dictate their long-term strategies, often leading to impulsive and poorly timed actions.

- Insufficient diversification: Familiarity bias—the preference for well-known investments like one’s own company stock or domestic markets—can cause investors to hold undiversified portfolios, increasing risk.

Why The Global Market Portfolio?

If there’s one thing that’s certain in economics, it’s that the world is now glued together with market data, money, and trade—like a giant financial group chat that nobody can leave. And no matter how many nationalist or protectionist trends pop up like bad Wi-Fi signals, globalization just keeps reloading. Sorry, isolationists—it’s not a phase, it’s a feature. If you don’t want to play, go build an off-grid cabin, cover everything with tinfoil to keep the evil spirits from StarLink away and try to survive off a patch of vegetables, wild berries and squirrel meat.

In the meantime, let’s zoom out and look at why the global financial system is a smart base case for understanding risk-adjusted returns.

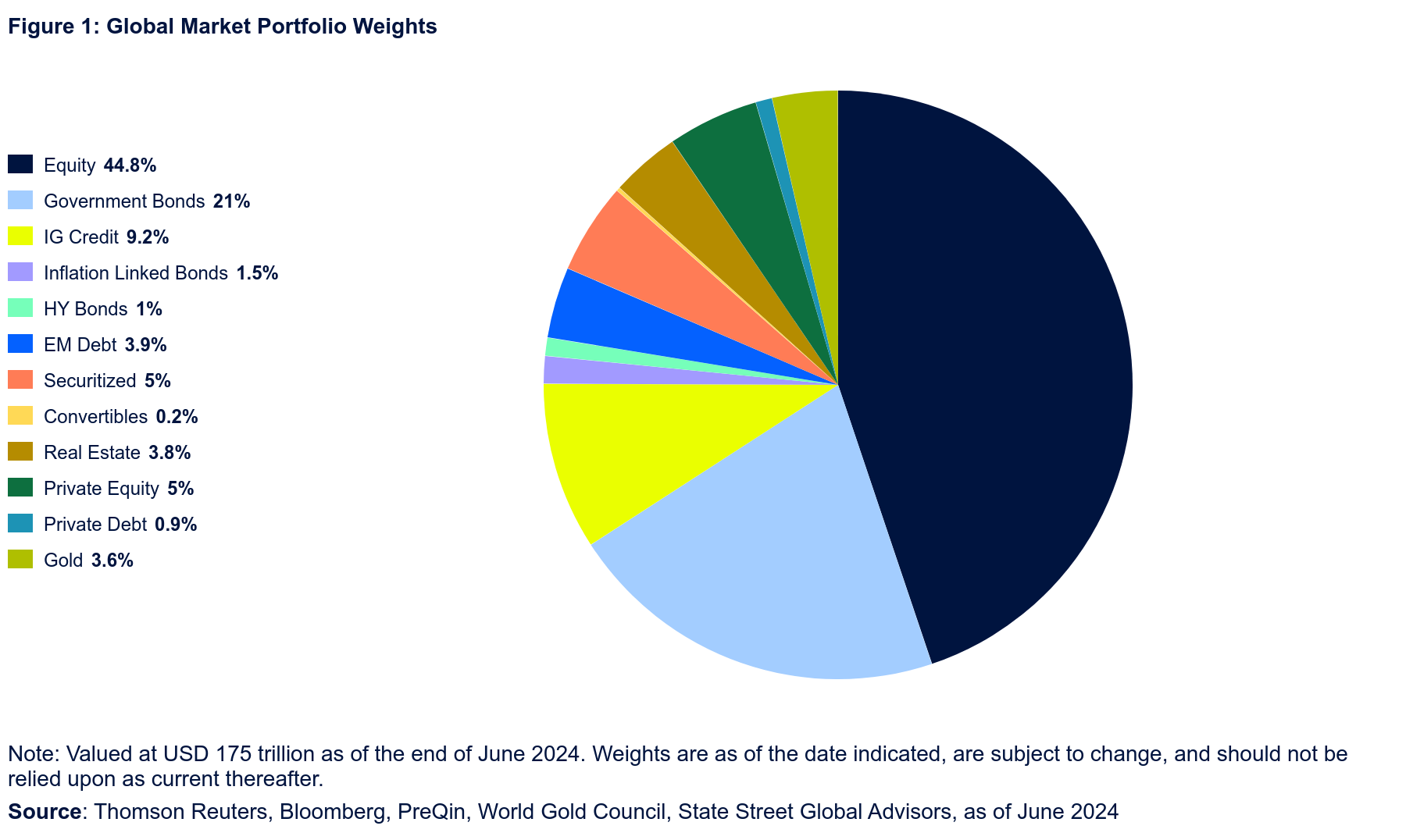

The Global Market Portfolio is one of the most ambitious concepts in finance: an attempt to map the entire universe of risky investable assets on Earth. It’s the financial equivalent of trying to chart every star in the sky. It has profound implications for how we think about diversification, risk, and the design of investment products like the Target Date Fund.

At its core, the Global Market Portfolio represents the aggregate holdings of all investors in all risky assets: stocks, bonds, credit, real estate, commodities, private equity, cryptocurrencies, antiques, watches, and so forth. It’s basically anything and everything that humans consider “an investment” that can be publicly traded and thus weighted by market capitalization. It’s the ultimate benchmark of passive investing, a portfolio that reflects the collective wisdom (and folly) of every market participant in all earthly markets. If you believe markets are broadly efficient, then this portfolio is the most diversified, most neutral, and arguably the most rational portfolio an investor can hold.

This idea intersects directly with Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). MPT teaches us that diversification reduces risk without necessarily sacrificing return. Sharpe’s Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) takes this further, suggesting that the market portfolio is the only risky portfolio investors should hold, and that all other assets should be evaluated based on their covariance with it. In this framework, the Global Market Portfolio isn’t just a theoretical construct: it’s the optimal portfolio for all investors, assuming they have the same expectations and preference to achieve the highest returns with the lowest long term risk.

The Long Game

Anne Scheiber retired from the IRS in 1944 at age 51 with only $5,000 in savings (90k inflation adjusted) and a $3,100 annual pension (56k adjusted) . She began investing in quality stocks and never sold. She lived extremely frugally and let her portfolio compound for over 50 years. When she died in 1995, her estate was worth $22 million, which she donated to Yeshiva University.

Ronald Read worked as a gas station attendant and mechanic in Vermont. He lived frugally and quietly invested in blue-chip dividend-paying stocks over decades. By all appearances, he was of modest means and social status. When he died in 2014, he shocked his community by leaving $8 million to local charities and his family. His secret? He consistently invested, never touched his portfolio and reinvested dividends.

A chess master must choose an opening strategy early in the game. It defines the tempo, structure, and possibilities. A poor opening limits future moves. A wise opening offers flexibility and defense. But once chosen, the game unfolds within its constraints. Investing is not bound by the strict rules of a chess game but it is constrained by choice and time.

Investing is a game of statistics. The most common mistake among active investors, both professional and amateur is a misunderstanding or underestimation of tail risks, which is the probability that as you chase returns that deviate from the broad market average, the more likely catastrophic losses will occur. Reducing tail risk involves implementing strategies that protect against severe drawdowns, such as investing in broad market index funds, using put options, diversifying investments, or maintaining cash reserves. These strategies aim to minimize potential losses from unexpected events and systematic risk, thereby enhancing overall portfolio stability and longitudinal performance.

A common psychological blunder is expecting that the rate of return over the past one, three, five or even ten years is reasonable evidence that it will continue. For individual stocks or asset classes, price appreciation in isolation is a useless metric: that’s betting on a thesis or outright gambling. Funds are usually different because they are bundles of assets that almost always provide some degree of diversification. Experienced investors know that ten years is not an adequate sample size to draw such a conclusion. Academics argue that even twenty is inadequate. And the longer any investment experiences price appreciation, the more likely it will attract speculative valuations and lead to a precipitous correction, following the “iron law” of mean reversion.

When presented with a buffet of investment choices, the meager average returns of large total market funds are unappealing compared to other options. Why would you choose an investment averaging a 6-7% CAGR when you can get 15% or even 50%? Total market equity funds that track indexes like the Wilshire 5000, CRSP US Total Market, Russell 3000 and FTSE Global All Cap offer the most reliable long term equity returns with the lowest drawdowns because they benefit from the most statistically significant sample size, and therefore represent the best standard distribution with the least tail risk.

Statistical significance is one of those things that sounds intimidating: like something whispered in the halls of academia by people wearing tweed and elbow patches: but it’s actually just a fancy way of saying, “Are we sure this isn’t just dumb luck?”

Imagine you flip a coin five times and get heads every time. You might think, “Aha! This coin is magical!” But flip it 5,000 times and get heads 2,500 times? Now you’re seeing the truth: it’s just a coin, not a wizard. That’s statistical significance in action. The more data you have, the more confident you can be that your results aren’t just a fluke caused by randomness or wishful thinking.

This is where sample size comes in. Small samples are like trying to judge a restaurant based on one bite of a soggy French fry. Large samples? That’s like eating the whole menu twice and then writing a Yelp review with authority. In finance and research, sample size is everything. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) are built on the idea that we can use historical data to estimate future risk and return. But if your data set is tiny or garbage-quality, your predictions are about as reliable as a weather forecast from a fortune cookie.

Now let’s talk about concentration: putting all your money into one or a few assets. It’s the financial equivalent of betting your life savings on a single horse because it “looked confident.” Sure, it might win. But it might also trip over its own hooves and eat grass while the others gallop past. Concentration is risky and frankly, highly likely to fail unless you have insider knowledge or a time machine and an exit strategy. Diversification, on the other hand, is like owning a whole stable of horses. Some will be slow, some will be fast, but overall, you’re more likely to finish the race with your dignity (and portfolio) intact.

This brings us to the Global Market Portfolio: the ultimate buffet of investable assets. By investing in the entire global market, you’re increasing your sample size to include every asset class and geography. That’s like flipping every coin on Earth and averaging the results. The statistical power of large numbers kicks in, smoothing out the bumps and giving you a more reliable, risk-adjusted return.

This approach doesn’t just reduce risk, it often improves returns relative to that risk. It’s the magic of diversification. You’re not trying to find the one golden goose. You’re buying the whole farm. The Global Market Portfolio is the ultimate haystack of haystacks. It’s the sum total of human financial activity, and by owning it, you’re letting the collective wisdom of the market work for you.

Because TDFs must serve millions of investors with vastly different financial circumstances, they rely on the statistical power of broad diversification. Many of the most successful TDFs — like those from Vanguard, BlackRock, and T. Rowe Price — anchor their equity allocations to global market weights. That means they don’t just invest in U.S. stocks; they include international equities, emerging markets, and global bonds. Blackrock’s iShares Lifepath ETF series even introduces REITS, annuities and may even add cryptocurrency if MSTR stock’s rise in the Russell 1000 isn’t an adequate proxy for the growth of that asset class. This approach mirrors the Global Market Portfolio, offering exposure to the entire investable world.

Vanguard’s research, particularly from Roger Aliaga-Díaz, emphasizes the importance of global diversification in Target Date Funds. In a recent Vanguard study, Aliaga-Díaz noted that while U.S. equities have outperformed international stocks over the past decade, chasing performance leads to concentrated risk. He argues that the logic of diversification applies at every level: including geography: and that the Global Market Portfolio remains a robust foundation for long-term investing. This is especially critical for TDFs, which must balance growth and preservation across decades.

Morningstar’s 2025 research echoes this sentiment. It highlights how the most successful funds have embraced global diversification, low fees, and disciplined glide paths. The report shows that Target Date Fund assets reached $4 trillion in 2024, with Vanguard alone adding $35.1 billion that year. These funds aren’t just popular: they’re delivering real-world results, thanks in part to their alignment with the principles of the Global Market Portfolio.

Academic research supports this approach. Studies by researchers like Ronald Doeswijk, Laurens Swinkels, and Pim van Vliet have attempted to estimate the composition of the Global Market Portfolio over time. Their work shows that equities typically make up about 50–60% of the global investable universe, with bonds, real estate, and alternatives comprising the rest. TDFs often mirror these proportions, especially in their early stages, before shifting toward fixed income as retirement nears.

Financial Advisors

But let’s be honest, how could the “average mode” one click simple algorithmic retirement fund possibly be better than doing your own research, due diligence, watching the market news, reading every issue of Forbes and The Economist cover to cover to understand the “macro trends” and actively managing your portfolio yourself or even in conjunction with a financial advisor who is a trained professional?

Professional financial advisors are a bit like dating apps: some are genuinely looking out for your long-term happiness, and others are just trying to sell you something shiny before ghosting you with a 1.5% annual fee. It’s a mixed bag: there are brilliant, ethical advisors who help clients navigate complex financial terrain with grace and wisdom. And then there are the ones who think “fiduciary” is a type of Italian pasta and who recommend annuities like they’re handing out candy at Halloween.

Let’s start with the good ones. Fee-only fiduciary advisors are unicorns who are legally obligated to act in your best interest. They’ll help you plan for retirement, minimize taxes, and avoid buying that third rental property in a flood zone. They’re worth their weight in low-cost index funds. But they’re not the norm.

The typical financial advisor, especially the kind you meet at your local brokerage firm, is not so much a financial planner as a well-dressed smooth-talking salesperson with a Series 7 license and a quota to hit who pretends to be your friend. These folks are incentivized to push products that generate commissions, like actively managed mutual funds, structured notes, or insurance-based investments with fees so high they should come with a warning label. According to the SEC, compensation arrangements — like 12b-1 fees, revenue sharing, and marketing support payments — create conflicts of interest that can skew advice away from what’s best for the client.

SmartAsset notes that these conflicts can subtly (or not-so-subtly) affect the advice you receive, leading to higher costs and less optimal outcomes. Advisors may steer you toward fund families that pay them more, or recommend share classes with hidden fees. And because they’re trying to keep you happy (and invested), they often cater to your worst behavioral instincts: like selling during a downturn or chasing last year’s hot sector.

Now compare that to a Target Date Fund. It doesn’t care about your feelings. It doesn’t flinch when the market drops. It doesn’t try to sell you anything. It just quietly rebalances, adjusts your asset allocation based on your retirement date, and charges a fraction of the fees. According to research by the Oblivious Investor website, the average DIY investor using a Target Date Fund will likely outperform the average investor using a typical advisor, because the fund avoids behavioral mistakes, keeps costs low, and sticks to a disciplined simple rules-based strategy.

And let’s talk about fees. A Target Date Fund from Vanguard might cost you 0.08% annually. A typical advisor-managed portfolio? Try 1% for the advisor, plus another 0.5% for the funds they recommend. That’s like paying $100 for a sandwich that costs $8 at the deli next door: except the expensive sandwich also comes with a side of regret and underperformance.

So yes, some advisors are fantastic. But many are just glorified product pushers with a knack for making expensive mediocrity sound like bespoke financial genius. If you’re not careful, you’ll end up with a portfolio that’s more about their commission than your retirement. Meanwhile, the humble Target Date Fund: boring, automated, and statistically brilliant: just keeps doing its job. No drama. No sales pitch. Just results.

But wait, “Target Date Funds are too generic! They don’t know me. They don’t know my dreams, my debts, my dog’s vet bills. Why should I trust a fund that treats me like a spreadsheet cell?” Fair point. These funds don’t ask about your side hustle, your crypto obsession, or your belief that some moonshot AI stock will fund your retirement and your moon base. They’re one-size-fits-all, like those stretchy pants that claim to fit everyone but somehow flatter no one.

Then there’s the “I can do better myself” crowd. These are the folks who believe they can time the market, pick the next Amazon, and rebalance their portfolios with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker. In reality, they often behave more like someone trying to fix a leaky faucet with a chainsaw. According to MIT Sloan’s research, retail investors tend to hold too much in equities when young and fail to reduce risk as they age: leading to portfolios that are dangerously exposed to market downturns. The set of skills and temperament required to make money are distinct from the skills and temperament to preserve it, and thus why the wealthy rely on fiduciaries who will tell you their number one objective is risk management.

And let’s not forget the “I want control” argument. Some investors bristle at the idea of a fund automatically adjusting their asset mix. They want to be in the driver’s seat, even if they’re not entirely sure where the road goes. But here’s the thing: TDFs are like self-driving cars for your retirement. They don’t need you to steer, and they’re surprisingly good at avoiding potholes.

Survivorship Bias

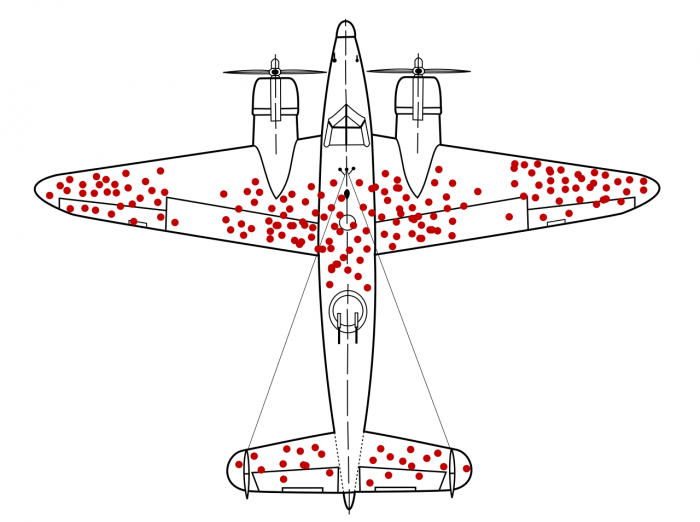

Now, here’s the twist: despite all the criticisms, Target Date Funds are shockingly effective. Like, “How is this working so well when most people don’t even know what a bond is?” effective. When front-line soldiers in the first and second world wars were asked how they rationalized going into battle despite knowing the substantial chance of death, they almost universally respond with variations of the same theme: you know the odds and think that it’s going to happen to the other guy, but not to you, that you’re special, and the longer you stay alive, the more you believe it’s true, even though the longer you engage the more likely you are to die. This is what’s known in statistical science as survivorship bias. After decades of low inflation and one of the longest bull markets in history, many investors have grown complacent. They’ve never seen a real bear market, and they think risk is something that happens to other people. TDFs quietly protect them from their own overconfidence.

During World War II, the U.S. military faced a critical problem: bombers were being shot down by enemy fire, and they needed to figure out how to reinforce the planes without adding too much weight. Initially, they examined the bullet holes on aircraft that returned from missions, assuming that the most damaged areas should be reinforced. But statistician Abraham Wald, working with the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University, saw a flaw in this logic. He realized that the military was only analyzing planes that had survived their missions, ignoring the ones that had been shot down. This oversight was a classic case of survivorship bias—drawing conclusions from a subset of data that excludes failures. Wald argued that the bullet holes on returning planes showed where damage could be sustained without causing a crash. Therefore, the areas with little or no damage on surviving planes were likely the vulnerable spots—because if those areas were hit, the aircraft probably didn’t make it back. Wald recommended reinforcing the least damaged areas, a counterintuitive but brilliant move that ultimately saved lives. His insight became a foundational example in statistics and remains a powerful lesson in how to think critically about data.

The Investment Company Institute found that when properly measured, TDFs perform just as well as other mutual funds on a risk-adjusted basis. They diversify globally, rebalance automatically, and reduce equity exposure as retirement nears. That’s not just smart: it’s statistically brilliant. They’re designed to counteract the behavioral mistakes that plague retail investors: chasing performance, panic selling, overconcentration, and forgetting to rebalance.

The average retail investor may understand the general principle of diversification, but aren’t quants, and have no idea what the covariance and risk of their portfolio is. TDFs, by contrast, spread risk across thousands of assets, tapping into the statistical power of large numbers. It’s like upgrading from a dartboard to a GPS.

So yes, Target Date Funds may seem boring. They don’t promise moonshots or meme magic. But they do offer something far more valuable: a disciplined, data-driven strategy that quietly outperforms the chaos of DIY investing. For the vast majority of investors: especially those who think “glide path” is a ski term: they’re not just good. They’re a financial life raft. And in a sea of behavioral bias and market noise, that’s worth holding onto.

The intersection of the Global Market Portfolio, Modern Portfolio Theory, and Target Date Funds is a masterclass in financial design. It’s about using the best available data, theory, and behavioral insight to create a product that works for the many, not just the few. It’s about trusting the market, embracing diversification, and letting time do the heavy lifting. And for millions of investors, it’s about quietly owning the haystack: one retirement year at a time.