Asset price appreciation often feels less like a rational process and more like a group project where everyone’s just copying the kid who guessed right last time. Speculation and returns chasing drive the show, with investors piling into whatever’s hot—not because it’s fundamentally sound, but because they saw a chart that went up and thought, “I want that.” Sentiment, in this context, is just a fancy word for collective FOMO. At the end of the day, most people don’t care why the number goes up, only that it does—and preferably in bold font with a green arrow.

Markets are supposed to be rational, but watching them is like attending a group therapy session run by caffeinated squirrels. Prices swing wildly because someone sneezed during a Fed meeting or because a billionaire tweeted a meme. Entire sectors can soar because investors suddenly decide that lettuce delivery via drone is the future. Meanwhile, solid companies with actual profits get ignored like the kid who brought a calculator to a party. If markets are a reflection of collective wisdom, then that wisdom occasionally wears a clown nose and invests in pet rocks.

Price appreciation is fundamentally speculative because it reflects investor sentiment rather than intrinsic value. In the absence of dividends or stock buybacks, returns rely solely on future buyers being willing to pay more—essentially betting on continued optimism. If a company that never pays a dividend or repurchases shares is trading at 36 times forward earnings, is there any evidence that it will ever “grow up” and pass any of those earnings back to investors? Seventy years ago, stocks that didn’t pay dividends were considered useless. Today they dominate the market. Market prices frequently react to narratives, forecasts, and momentum rather than concrete earnings or cash flow. Even for established companies, valuations can swing wildly based on macro trends or hype, underscoring how much of the appreciation is driven by perception rather than performance.

Perhaps it’s uniquely American that, as a society, we’ve outsourced a significant portion of our national retirement strategy to a system that resembles a private casino. The stock market and a casino may seem worlds apart—one draped in suits and spreadsheets, the other in neon and noise—but statistically, they share a surprising kinship. Research shows that over 80% of day traders lose money, a figure eerily close to the house edge in blackjack, where the casino wins about 51% of the time. Both environments lure participants with the promise of outsized returns, yet most walk away lighter in the wallet. The difference? At least in Vegas, they hand you free drinks while you lose your savings. In the market, all you get is a quarterly earnings call and a headache.

Risk-adjusted returns matter because they tell you whether the juice is worth the squeeze. It’s not just about how much you make—it’s about how much stomach acid you had to produce along the way. A portfolio that earns 8% with wild swings isn’t necessarily better than one that earns 6% with smooth sailing. High returns may look attractive on paper, but if they come with significant fluctuations, there’s a real danger that the value of the investment could drop just when you need to access it—such as during retirement.

Index funds were an innovation that exploited the collective wisdom of markets to offer a low cost alternative that usually outperforms active fund management. A cap weighted index fund that tracks a broad enough market has the potential to mirror a statistical distribution that smooths out the wild bets of impulsive gamblers and methodical analysts while reaping sufficient gains from the winners in the power law distribution. But as the popularity of these products surge, we may be reaching a critical inflection point where their crude algorithmic passive flows distort the very markets their underlying indexes track. If everyone is a passenger, who’s steering the ship?

John Bogle was a great man, famous for introducing index funds to the retail market through Vanguard in 1975. His philosophy is often characterized as “buy and hold a stock market index fund.” That narrative is largely propagated by self-proclaimed disciples like J.L. Collins, and to a lesser extent by the large cohort of self-proclaimed “Bogleheads” who gather in forums, Reddit groups, and at annual conferences with a zeal that borders on religious. Bogle often repeated the same mantra as his colleagues and friends Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger —a quote from Albert Einstein—that “compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world.” Jack was widely recognized as an idealist with a contrarian streak, yet equally respected as a seasoned financial expert who oversaw major mutual funds for decades. The enduring culture he fostered at Vanguard, along with the deep admiration he earned from peers, speaks to his legacy. At his core, he was principled, fair, and unwaveringly ethical. He understood the nuanced risks associated with investing and consistently advocated for bonds as a straightforward method of hedging against the risks inherent in equities.

It’s noteworthy that many of Bogle’s acolytes like J.L. Collins, Rick Ferri and Paul Merriman are a product of the baby boom generation’s lifetime investment experience. Bogle belonged to a different generation whose views were shaped by the visceral impact of the Great Depression. Few from that generation are still with us, but for those whose parents or grandparents lived through that era, many observed that it often had a profound effect on their behavior—sometimes bordering on compulsion. This ranged from hoarding common goods and cash to a deep skepticism of the financial system, especially the stock market. Anecdotal stories abound of drawers and closets filled with pantry items, an inability to discard anything practical for fear it might one day be needed, and cash hidden under seat cushions, sewn into drapes, or tucked into nooks and crannies in the walls—only to be discovered later by renovators. These are the compulsions of individuals who lived through an extended period of severe scarcity.

Bogle entered his professional career when the public remained deeply distrustful of the stock market. He spent his early years trying to sell consumers on a new idea: that a balanced mutual fund of stocks and bonds offered a safer way to invest in the securities market. It was an uphill battle until the late 1950s, when the market was booming and investor sentiment had shifted—the future looked bright, the numbers always seemed to go up, and people wanted a piece of the action to get ahead or simply keep up with the Joneses. By the 1960s, there was an equity bubble. Bogle understood that stocks—even a portfolio of “diversified” companies or a broad-based index fund—were risky, and he never once advocated an all-equity portfolio for the average retail investor. In every interview, when asked about his personal allocation, he consistently replied that he held bonds. In his later years, he maintained a 50/50 allocation, which aligned with his default prescription for laypeople uncertain about how to invest—or the rule of thumb that your bond allocation should roughly match your age. To this day, Vanguard offers the original balanced Wellington Mutual Fund, founded in 1928, and their hugely popular Target Date Retirement Funds still include an allocation to bonds from the first day of the glidepath—often perceived as overly conservative by the modern risk-on investor.

Due to the popularity of index funds and ETFs that abstract away the underlying holdings, the distinction between bonds and stocks is often lost in the flood of advice offered by pop financial influencers. Many imply that stocks—and especially broad-based market index funds—grow through the “magic” of compounding, when in reality, equities, mutual funds, and even bond funds do not bear interest. In fact, the returns on many popular growth stocks—especially those that neither pay dividends nor engage in stock buybacks—are driven by speculative price appreciation hinging on investors’ confidence in the market’s ability to accurately value such assets. Interest is paid only on individual debt instruments or debt securities and is not the same as compound returns on a stock or blended investment ETF product, even if that product distributes dividends and interest from its underlying investments as a dividend. A bond, note, or bill is fundamentally different in that it is a debt contract that pays a fixed rate of interest. Even if a bond’s price fluctuates on secondary markets, and it doesn’t default, it ultimately returns to par—the principal amount at face value, which carries significantly less risk.

Explain It Like I’m Five

If we can’t explain something to a five year old, we may not understand it as well as we think. Here’s how we might do so.

Bonds are a way to make money on your savings through something called interest. Simply put, if you let your buddy borrow $100 for a year, you would not have access to that money for a whole year, so you might ask him to pay you a convenience fee in addition to returning your $100. Bonds work the same way. You can go on the internet and buy a $100 ten year treasury certificate from the U.S. government. You just loaned the government $100 for ten years, and they are willing to pay you interest for that time. They used to mail you a fancy parchment that looked like a big dollar bill, but they don’t do that anymore. But when they did, you could put it in a drawer or a safe place. In ten years, you could take it to a bank and the person at the bank would pay you the face value of $100 plus around $50 in interest, based on today’s 10 year bond coupon rate.

If you wanted to sell your treasury certificate earlier than ten years, you could do so in the secondary market where people buy and sell them. Bond prices fluctuate in this market. Why? If the government treasury is selling the same certificate today with a higher interest rate than the one you bought, that influences the price people would pay for your older certificate, not to mention the time remaining on the loan is less, so that’s taken into consideration. Secondary market pricing is a predictable formula. If your bond is worth more or less, don’t worry — you could decide not to sell it and the price always returns to the original value, or par value at maturity. No matter what, you’re going to get $150 after ten years.

The sad thing is, because the purchasing power of money decreases over time, you may not be any better off. If you like candy bars and the cost of a candy bar is 1.00 today, you can buy 100 candy bars instead of buying that treasury. If you bought the bond, and in ten years, a candy bar costs 1.50, you can still only buy 100 candy bars.

The Magical Compound

The popular conflation of compound returns and compound interest is subtly misleading. You can purchase an equity or an index fund of equities and bonds, and while it will compound returns when dividends are reinvested, the market price can still drop by 50% or more, eviscerating speculative gains.

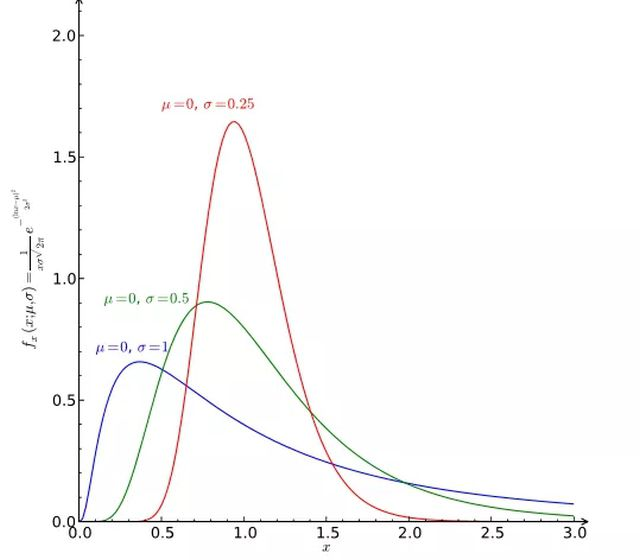

Portfolio strategies typically follow the idea that market returns follow a normal distribution. However, the concept of tail risk suggests that the distribution of returns is not normal, but skewed, and has fatter tails.

The fat tails indicate that there is a probability that an investment will move beyond three standard deviations. The chart below depicts three curves of increasing right-skewness, with fat tails to the downside—and which differ from the symmetrical bell curve shape of the normal distribution.

It can thus be incredibly challenging to heed the value of risk-adjusted returns. One perspective is that the only realistic choice for any investor is how much opportunity they are willing to sacrifice for capital preservation. Home owner’s insurance in coastal regions can be extremely expensive, but you’d have to be very wealthy or foolish to decline it. Yes, it’s almost a certainty that a 60/40 portfolio will underperform the S&P over twenty years in real terms, but over a ten or even fifteen year investment horizon it’s a completely different risk profile.

Bonds can play a surprisingly effective role in hedging against tail risk—those rare but severe market events that send portfolios into a nosedive. During periods of extreme equity market stress, investors often flee to safety, and U.S. Treasury bonds tend to benefit from this “flight to quality.” Historically, bonds have shown a negative correlation to stocks during crises, meaning they often rise when equities fall. This phenomenon, sometimes called “crisis alpha,” helps cushion the blow of a market crash.

For example, in the 2008 financial crisis, intermediate-term Treasuries provided strong positive returns while equities plummeted. Including bonds in a portfolio can reduce overall volatility and limit drawdowns, especially for retirees or anyone needing liquidity during downturns. Unlike speculative hedges like VIX futures or options, bonds offer positive expected returns over time, making them a more sustainable and cost-effective hedge.

Of course, this strategy assumes that the historical negative correlation between stocks and bonds holds up—which isn’t guaranteed in all environments.

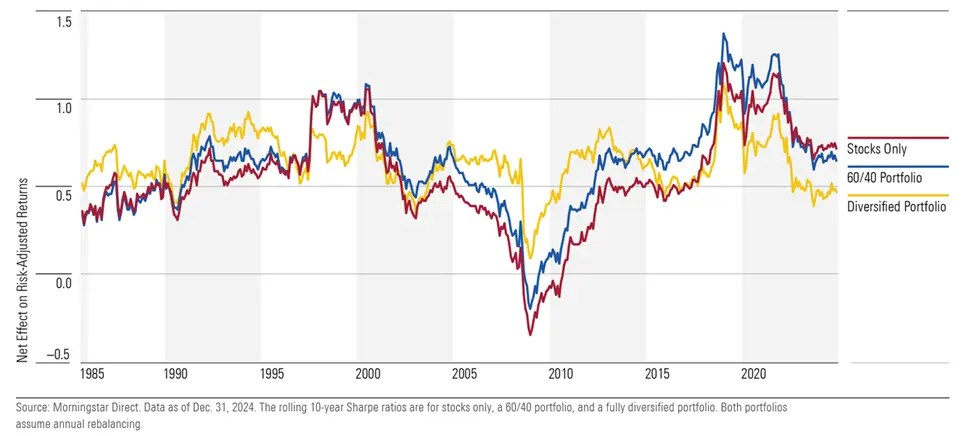

A recent report from Morningstar Portfolio and Planning Research reveals that the classic 60/40 portfolio—comprising 60% stocks and 40% bonds—outperformed a stocks-only benchmark roughly 83% of the time since 1976 on a risk-adjusted basis. Moreover, it consistently beat a more broadly diversified portfolio in every rolling 10-year period since early 2005. If you can plausibly achieve your objectives with a balanced and diversified portfolio that has better risk-adjusted returns, it’s worthy of serious consideration, because the market itself is changing structurally.

At a minimum, bonds are useful in a modern portfolio because they retain the purchasing power of “dry powder” over the long term better than cash, have a very low correlation to other assets, and provide ballast against volatility. The discipline of rebalancing annually to maintain a target allocation forces the portfolio to buy low and sell high. To be clear, bonds are often a drag on total returns long term. Bond funds alone are not an optimal investment unless the only objective is capital preservation.

So why bonds? Because the fundamental dynamics of the market are changing.

Passive Flows & Market Distortions in Stocks

Mike Green is chief strategist at Simplify, polymath, thought leader and evangelist in a growing field of research on the impacts of passive investing. He is a regular guest on various YouTube channels with a blisteringly sharp intelligence and subtle wit to boot. Green argues that passive investment flows are fundamentally reshaping market dynamics in ways that could be dangerous or even ponzi-like. He believes that as more capital floods into index-based strategies, it distorts price signals and inflates valuations—especially for large-cap stocks—creating a self-reinforcing cycle that could lead to severe market instability if those flows ever reverse.

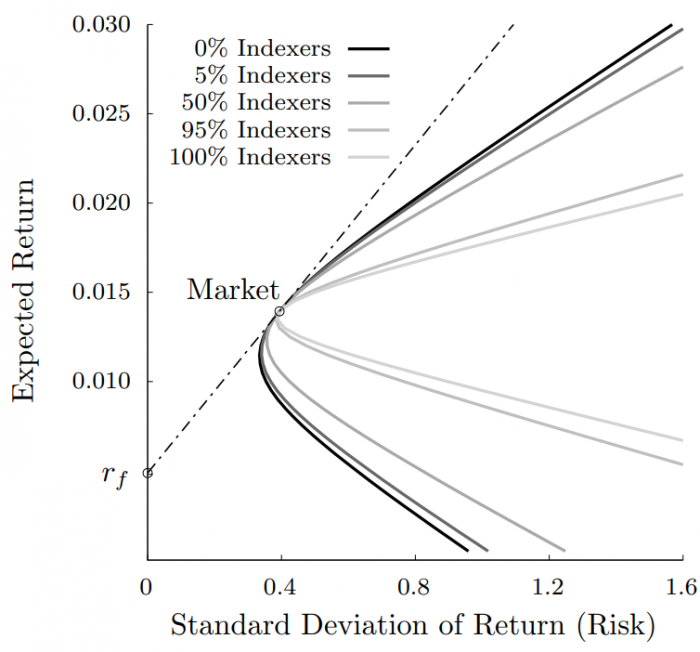

A 2019 study titled “The Distortion in Prices Due to Passive Investing“ by Shmuel Baruch and Xiaodi Zhang reveals that the rise of passive investing may be quietly undermining market efficiency. The researchers show that as more investors shift toward indexing—holding only the market portfolio—asset prices begin to reflect less information, leading to a decline in price efficiency.

While the market portfolio remains stable in terms of Sharpe ratio and risk, active portfolios suffer from reduced performance metrics and heightened idiosyncratic risk. The forward price of the market portfolio emerges as a minimal sufficient statistic, encapsulating all relevant information, while individual asset prices lose their connection to fundamentals. The findings raise important questions about the long-term implications of widespread indexing, suggesting that passive strategies may distort capital allocation and hinder the market’s ability to accurately price risk.

One of the more surprising findings in the study is that the asset’s sensitivity to movements in the overall market don’t all converge, even as passive investing becomes more dominant. You’d think that if everyone’s just buying the market portfolio—without regard to individual asset fundamentals—then all assets would start behaving like the market itself. That would mean their betas, which measure how sensitive they are to market movements, should all drift toward one. But that’s not what happens. The researchers found that assets still have distinct betas, meaning they respond differently to market changes. This suggests that even in a world flooded with index investing, some structural or informational differences between assets persist. It’s a bit counterintuitive, because it implies that passive flows aren’t completely homogenizing asset behavior. For investors, this means that risk modeling still matters and active strategies might still find opportunities by exploiting those differences. So while passive investing may be reshaping the market, it hasn’t erased the nuances of individual asset risk.

There’s growing evidence that the structural changes brought on by passive investing could amplify risks during periods of outward flows or exogenous shocks. As passive strategies increasingly dominate the market, they contribute to what researchers call “market inelasticity”—a condition where prices become highly sensitive to flows, rather than fundamentals. For example, when large sums are funneled into index funds, prices can inflate disproportionately, and when those flows reverse, the market may experience sharp corrections. A recent analysis by C WorldWide Asset Management likens this dynamic to a momentum-driven system that can lead to valuation bubbles and capital misallocation.

Moreover, studies from the Federal Reserve and academic institutions have shown that higher passive ownership tends to reduce market liquidity, increase bid-ask spreads, and heighten exposure to aggregate liquidity shocks and tail risks—meaning stocks become more prone to extreme price movements. These effects are particularly pronounced in large-cap stocks, which receive the bulk of passive flows but often have lower relative liquidity. In times of stress, such as a sudden market downturn or geopolitical event, the lack of active price discovery and diminished liquidity could exacerbate volatility and make it harder for markets to stabilize.

One of Mike Green’s astute insights is that this inelasticity from passive flows introduces a significant new relationship between market prices and employment. Where do most passive flows come from? That’s easy: 401k plans. Since the U.S. introduced regulations that require employers to opt employees into their 401k by default, employers must also provide a default investment package that meets certain quality criteria for people who lack an informed preference and need a responsible product. Guess what almost all of those default products are? Target Date funds constructed from passive index funds. Now, imagine what happens if we combine this price rigidity with a sudden 5% drop in employment with a corresponding termination of those 401k flows? Now imagine 10% unemployment in a feedback loop. Now combine that with the largest generational cohort in history hitting retirement around the same time, no longer contributing to their plan and legally obligated to start drawing down their 401k.

That’s a juggernaut of dumb money potentially toppling over.

In short, while passive investing offers cost efficiency and broad exposure, its growing dominance may leave markets more vulnerable to abrupt dislocations when the tide turns.

Passive Flows & Market Distortions in Bonds

Academic research has also focused on how passive investment flows are reshaping the bond market—and not always for the better. One of the key concerns is that passive strategies, especially in fixed income, may be contributing to a similar market inelasticity, where prices become more sensitive to flows than to fundamentals. A paper from T. Rowe Price highlights how passive bond funds, by mechanically buying and selling securities to match index weights, can distort price discovery and amplify volatility. Because these funds don’t participate in new issues and often rely on flawed sampling methodologies, they may miss out on better opportunities and inadvertently reinforce inefficiencies.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston also weighed in, noting that while passive investing has reduced some liquidity and redemption risks, it has increased asset-market volatility and industry concentration. Their research found that passive bond funds now account for about 30% of total bond fund assets, up from less than 5% in 1995—a dramatic shift that has implications for how credit spreads behave and how responsive the market is to economic signals.

Meanwhile, the Bank for International Settlements observed that passive flows in bond markets tend to be more stable than active ones during stress periods, but ETF flows—often used for passive exposure—can be quite volatile. This duality suggests that while passive investing can offer stability in calm markets, it may exacerbate swings during turbulent times.

In short, while passive bond investing has grown rapidly due to its low costs and simplicity, researchers caution that it may be dulling the market’s ability to price risk accurately, especially in times of stress or reversal. The takeaway? Passive strategies aren’t risk-free, and their growing dominance could leave the bond market more vulnerable to shocks.

Strategies

Several strategies can be employed to enhance portfolio resilience and adaptability:

- Diversification Across Asset Classes

Spreading investments across stocks, bonds, real estate, and international markets can reduce exposure to any single sector or geographic risk. This helps buffer against market volatility and sector-specific downturns. - Rebalancing Portfolios Regularly

Passive portfolios can drift from their intended allocation due to market movements. Periodic rebalancing ensures that the portfolio maintains its risk profile and avoids overexposure to overheated sectors. - Using Bond Ladders and Investment-Grade Bonds

To manage interest rate and inflation risks, investors can use bond ladders—staggered maturities that provide steady income and flexibility. Investment-grade bonds also offer lower default risk. - Incorporating Active Management Elements

While passive investing avoids frequent trading, integrating active strategies like tactical asset allocation or selective stock picking can help avoid overvalued sectors and improve downside protection. - Monitoring Liquidity and Tracking Error

Choosing ETFs and index funds with high liquidity and low tracking error ensures smoother execution and better alignment with benchmark performance. - Tax-Efficient Investing

Passive funds are generally tax-efficient, but investors should still monitor capital gains distributions and consider tax-loss harvesting to optimize after-tax returns. - Alternative Investments for Stability

Including non-correlated assets like mortgage notes or income funds can provide steady returns and reduce reliance on equity markets, especially during downturns.

By combining these strategies, investors can retain the benefits of passive investing—such as low costs and broad exposure—while proactively managing the risks that come with market shifts and structural imbalances.